The new Oklahoma school report cards reveal sad outcomes in urban schools, something high-stakes standardized testing and the first generation of primitive school grades have always sought to show.

The primary means for enforcing No Child Left Behind’s accountability-driven, market-driven goals involved producing a series of headlines about “failing schools,” with many reformers hoping that patrons would reject traditional public education for a market-driven alternative. Today’s more sophisticated school grades, however, tell a more complicated story. They can be a valuable diagnostic tool if we dare to analyze these new metrics the way they are intended.

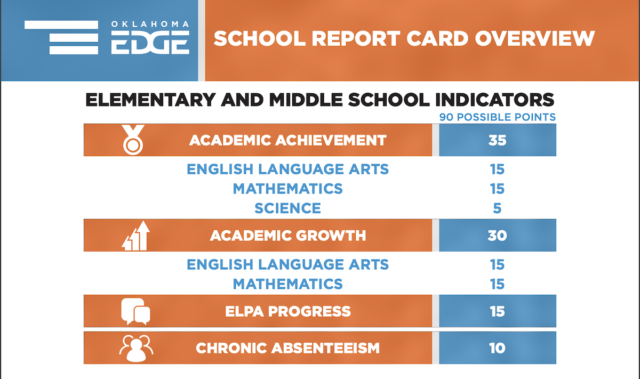

The best thing about Oklahoma’s new school grades system is that they document the extent of chronic absenteeism. Previous accountability systems excluded most chronically absent students on their school level report, thus encouraging poor districts to ignore their most vulnerable students.

The two worst things about the report card system are how it is far too difficult to find the most important data on virtual schools, such as Epic charters, and that it uses standardized tests and categories that are too rigorous for accountability purposes. The Epic conundrum is beyond the scope of this post.

Review Oklahoma’s new

school report cards

Oklahoma’s accountability tests are pretty comparable to the NAEP tests that aren’t supposed to indicate whether students are on grade level. Only a handful of places, like Shanghai, Korea and Boston produce high proficiency rates on these sorts of tests. Poor students who lack background knowledge will not be able to improve as fast as higher-skilled students on these more complex assessments.

We must not forget, however, that Oklahoma’s report cards were remodeled with the help of a 95-member task force representing educators, parents and other stakeholders. In my experience, most teachers have favored the type of rigorous test that Oklahoma adopted. In retrospect, I think we went too far, but like most of my colleagues, I initially supported tests that gave more emphasis on college readiness. I suspect that the new grade cards could be the best compromise that was politically possible.

Looking at OKCPS, Centennial

Local headlines about this year’s report card release focused on how 19 Oklahoma City Public Schools, or about one-fifth of the district, received F’s. Two elementary schools and Centennial High School received no points for preparing students for the next grade.

Centennial, the school where I taught, offers a sad snapshot. Students at the D-rated high school mostly came from the F-rated North Highland ES and the co-located F-rated Centennial MS, where large numbers of students are chronically absent, meaning they inevitably fall further behind. Chronic absenteeism at Centennial HS is 30 percent.

Forty-four percent of Centennial’s economically disadvantaged students earned basic or proficient on composite scores but, as it should be, those numbers counted little toward the overall grade. On the much more important metric, 81 percent failed to meet the performance target, meaning that the school received a zero on academic achievement. By comparison, 76 percent of economically disadvantaged OKCPS students failed to meet the academic targets.

On the other hand, Centennial’s graduation rate was 86 percent, which is the state average, as English-language learners did well enough in progressing toward their targets to earn the school a C. The majority of Centennial students were exposed to college readiness instruction/guidance, earning the school a B. (Both Centennial high and middle schools will be closed under the district’s new Pathway to Greatness plan.)

How could it be possible for students to miss so much school and fail to progress while graduating at such a high rate and engaging in college-readiness instruction? Some or most of those graduation numbers must be due to “passing kids on,” but it is more complicated than that. The outcomes also indicate that teachers and students worked hard toward meeting the goals that were placed before them. The goals may have been contradictory, concentrating on remediation to meet both basic graduation requirements and the opposite — learning for college readiness.

Success portfolios > standardized test scores

The question, however, is whether educators and students were challenged to “work hard” or “work smart”?

And the first hint toward such answers — as well as answers to the bigger questions of how the Grade Cards should be used — comes from Tulsa. In comparison to OKCPS, an even higher percentage of Tulsa schools (25 percent) received F grades.

Tulsa Superintendent Deborah Gist responded with an implausible claim that the district’s own assessments are more meaningful, and show more progress. Such benchmarks tend to encourage shallow in-one-ear-ear-and-out the-other teaching and learning. Gist’s statement isn’t proof that this is happening, but it raises the type of question that report cards should lead to. Gist said students lose five to six months of progress during the summer.

Yes, the “summer slide” is a huge problem which the National Summer Learning Association says can explain why low-income kids can be up to three years behind by fifth grade. Before test-driven school reform and budget cuts undermined the effort, the OKCPS had science-based plans for tackling the problem with a full-year calendar where summer courses were supposed to be devoted to holistic learning, not remediation. But the national estimates are that economically disadvantaged students lose two to three months in reading achievement over the summer, as higher-income peers tend to make slight gains out of school.

If Tulsa students’ summer learning loss is twice the norm, the district should ask why. Are the 13 Tulsa central office administrators who were trained in the teach-to-the-test-loving Broad Academy pushing Tulsa educators into a discredited, 21st century version of “drill-and-kill?”

The Tulsa World quoted the principal of the failing Anderson Elementary, Tracy Thompson, who said: “As this news is coming out, my teachers are like, ‘Oh my gosh, I would rather build a portfolio for every kid to measure their success instead of just assigning a score to every child.'”

Such a lament was completely justified before the Hofmeister administration set out to reverse the educational malpractice that was virtually mandated a decade before.

Today, even Gist, who was one of the nation’s most notorious corporate reformers, bemoans the need for schools to “spend much of their year digging out of the hole left behind.” But, now, why can’t educators return to holistic, meaningful instruction using portfolios for assessment? Why can’t our poor children of color be provided the out-of-school opportunities for lifelong learning that affluent kids receive the entire year?

Tulsa not only seems to suffer more from the worst of test-driven, competition-driven reform, but its school partners also illustrate a better way to use the Report Cards. The Impact Tulsa 2018 Community Impact Report acknowledges, “Overall, Tulsa-area students are in a bottom tier of performance for eighth-grade math nationally.”

The report doesn’t hide the “broader, more troubling conclusion: For too many of our students, Tulsa is not a land of opportunity.” It documents “an opportunity crisis,” which requires “education, business, faith, nonprofit, civic and philanthropic communities to ‘own this reality and collectively work to eliminate systemic barriers that trap our students of color and low-income students.’”

And that is the lesson we should bring to the reading of report cards. The reform effort to deputize individual educators as the agent for overcoming legacies of poverty and trauma was doomed to fail. Now we know that school improvement must be a community effort. Teachers should allow themselves to mourn over the grades but then get back to work playing our position in the team effort to restore meaningful instruction and trusting relationships that have been sacrificed to test scores.