To understand the scope of the crisis Oklahoma faces because we lead the nation — and the world — in incarceration, consider this: If Oklahoma released half of our people behind bars today, we would only drop to the national average while still locking up more people than any other country in the world.

That’s a shocking statistic that should compel action. We must get out of No. 1 in incarceration and stop prison growth now.

But some have begged to differ, saying modest criminal justice reform proposals made this session are too much, too fast.

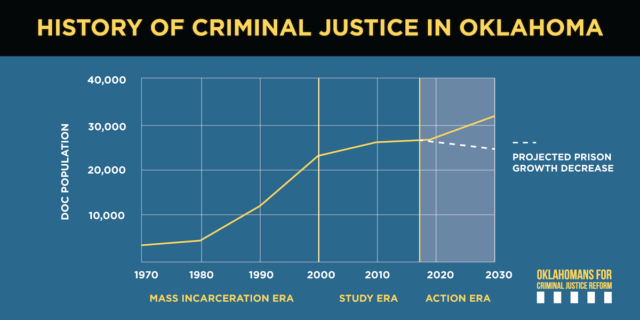

Let’s unpack that by first understanding how we got here. Oklahoma’s staggering prison population is a challenge 50 years in the making and spread across three eras: the Mass Incarceration Era, the Study Era and the Action Era.

The ‘Mass Incarceration Era’

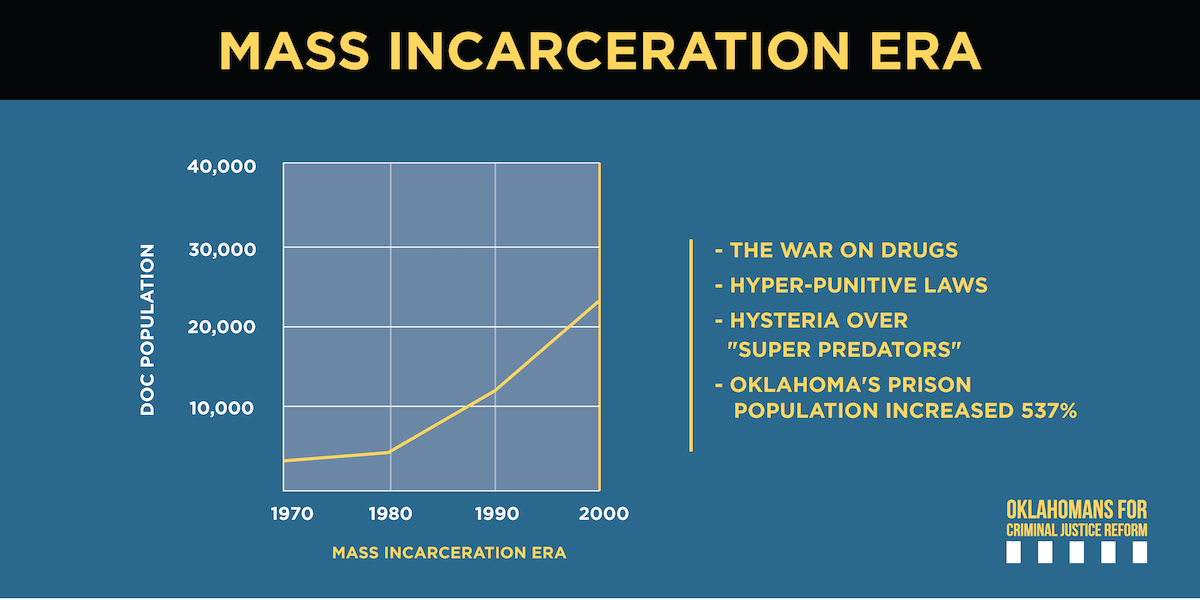

Since 1970, Oklahoma’s prison population has grown by more than 500 percent, while the state’s population grew only 56 percent. For most of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, new crimes with tougher penalties were regularly added to the books, creating generational cycles of incarceration.

From the war on drugs in the 1980s to truth-in-sentencing laws in the 1990s, fear was the popular driver, and increasingly harsh punishment was the response. Hysteria over urban crime and “superpredator” children gripped the nation.

Oklahoma’s challenge was compounded by closure of most of the state’s mental health hospitals in the 1960s, which led many mentally ill Oklahomans to self-medicate with illegal drugs due to the lack of treatment services. Then, instead of providing treatment, we started sending them to prison.

In 1987, Oklahoma passed its first three-strikes law. At the time, it applied only to drug trafficking and allowed the opportunity for parole after 10 years. Two years later, the law was amended to apply to all crimes, with no parole option.

In 1991, Oklahoma became the world leader in the incarceration of women and has remained so ever since. “Tough on crime” was politically expedient and our elected officials made the most of it.

The ‘Study Era’

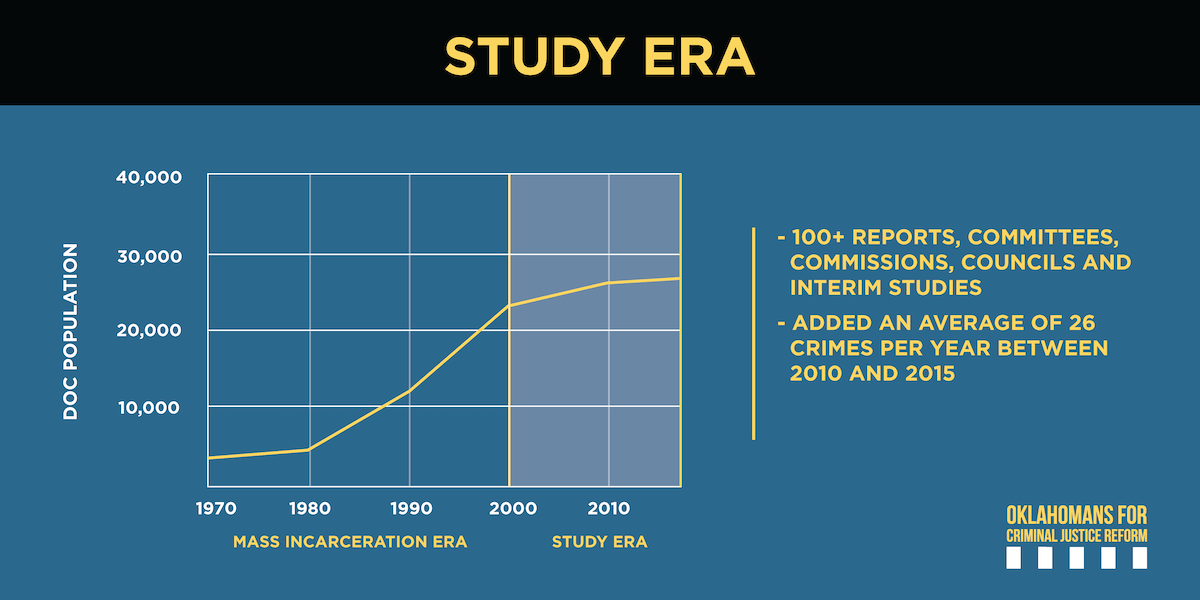

By the turn of the century, Americans across the political spectrum began to realize these types of incarceration policies had created a crisis. Studies were conducted from coast to coast. The magnitude of the problem became apparent.

Oklahoma was no exception. In the past 25 years, Oklahoma has used more than 100 committees, commissions, task forces, interim studies and reports to study our mass incarceration problem. From the school-to-prison pipeline to our penchant for locking up women, from the negative impact of mass incarceration on children to sentencing kids to die in prison, we have studied it. And studied it. And studied it again.

Meanwhile, Oklahoma leaders continued to criminalize and demand retribution rather than rehabilitation. As recently as 2001 and 2007, the Legislature tacked the 85 percent requirement — a harsh mandatory minimum initially reserved only for the most serious violent crimes — onto nonviolent drug offenses. One study found Oklahoma added an average of 26 new crimes to the books every year between 2010 and 2016, even as other studies showed such approaches counterproductive to improving public safety.

The ‘Action Era’

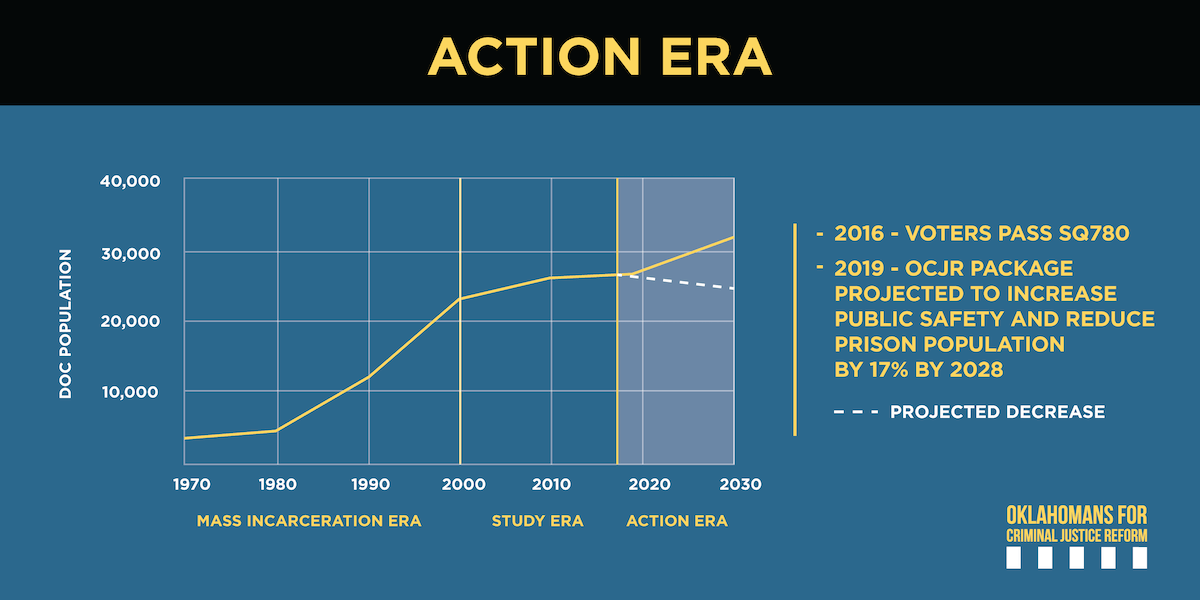

But in 2016, Oklahoma voters took action and passed State Questions 780 and 781, via initiative petition. The former reduced simple drug possession and low-level, nonviolent property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors; the latter created a drug treatment fund that is scheduled to receive its first appropriation July 1 of this year.

In 2017, the Oklahoma Justice Reform Task Force released a comprehensive, data-driven plan that laid the groundwork for meaningful reform. Last year, the Legislature passed a handful, but not all, of its recommendations.

Today, Oklahoma has the opportunity and a moral imperative to take action. Many elected officials recognize the magnitude of the crisis and are willing to take corrective steps. Gov. Kevin Stitt has made criminal justice reform a priority and has major potential to be a transformative leader in solving Oklahoma’s imprisonment crisis. Numerous Oklahoma legislators in both parties have authored thoroughly researched bills that will stop prison growth.

Naturally, there are a vocal few who claim Oklahoma is trying to do too much, too fast on criminal justice reform. They want to hit the brakes and halt progress. Unsurprisingly, many want another study or to convene another task force.

Locking up our fellow Oklahomans by the tens of thousands in the 1980s and 1990s was “too much, too fast.” The modest reforms making their way through the Legislature this year hardly fit that description. For those whose lives have been wrecked by mass incarceration, we are doing “too little, too late.”