(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Jennifer Palmer of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

Moore Public Schools’ plan to discontinue a weekly class for its gifted students has raised concerns with state advocates for gifted education and also rankled parents and teachers within the district.

The president of an Oklahoma association for gifted students said the move by such a large district is a “red flag” and sends a message that gifted students don’t need this type of special service. However, there’s no indication so far that many districts are eliminating gifted programs.

Moore Public Schools is the state’s fourth largest district and received $2.7 million in state funds for gifted students this school year, more than any other district, according to state data.

The district announced last fall it will no longer offer Students Experiencing Appropriate Research and Creative Happenings, or “Search,” a specialized class for students who score in the top 3 percent of intellectual ability. Beginning in 2019-20, Moore is implementing a STEAM class (science, technology, engineering, art and math) for all elementary students and plans to group gifted kids together within that class.

Billed as a great opportunity for all students, Moore says its STEAM program will increase consistency in curriculum across the district as well as give gifted students opportunities to accelerate. It discontinued Search to allow all students to participate in STEAM.

Cynthia DePalma, president of the Oklahoma Association for the Gifted, Creative & Talented, said Moore’s decision could exacerbate an attitude among some school administrators that because gifted students are smart, they’ll be fine.

“It’s a savage inequity,” DePalma said. “Gifted education is not a program. Gifted and talented children are a unique population – it’s about meeting the needs of these kids.”

Moore plans to continue testing students for giftedness to receive gifted funding, but spend it on the STEAM class, according to information released by the district. The district’s gifted education plan for 2019-20 has been submitted to the state Education Department but hasn’t yet been approved.

“The way we’re going to work with our gifted students is going to look very different,” said Moore Superintendent Robert Romines, emphasizing the district is not doing away with gifted programming. He said some parents and teachers have misunderstood the plan.

But many parents don’t agree.

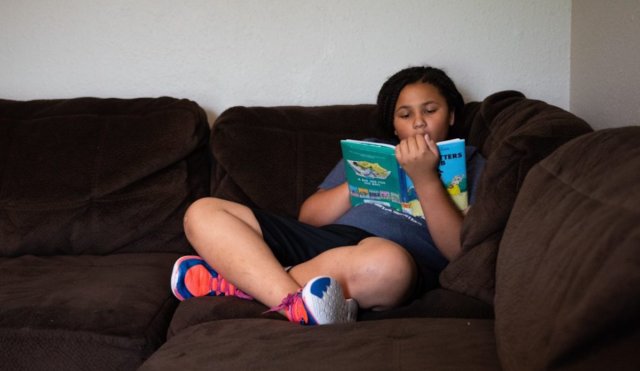

“We’re definitely losing something,” said Jamie Eneff, whose son, Andre, is in third grade at Sky Ranch Elementary and participated in Search this year. “The general population of kids is going to gain from it, and I’m happy for that. But I’m sad for what my son is going to lose.”

Eneff said his son complains about the constant worksheets students complete in his normal classroom. “He’s just not engaged,” she said. “It’s a relief for him to get to leave and have (Search).”

Other students describe Search as the place in school where they can express themselves, where people understand them and are on the same thinking level. “It’s my home away from home,” one student wrote after the announcement the program was ending, according to letter provided by a Search teacher.

‘Left out of learning’

Oklahoma schools served 96,149 gifted students in 2017-18, according to state data.

Oklahoma schools are required by law to provide gifted education, but districts are given flexibility to design programs to serve their students. A specific class for gifted students is one of several options districts have but the approach is the most common, particularly in elementary school, according to the state Education Department.

Oklahoma is also one of just four states to fully fund gifted education, according to the Davidson Institute, a nonprofit that supports gifted young people. That’s an estimated $55 million this school year.

DePalma said historically, Oklahoma has had strong advocacy for gifted education but it has tapered off. And there is such a focus now on bringing low-achieving students up to a basic standard that districts often focus on the “bubble kids,” those close to meeting proficiency, she said.

“Kids who are already at or above meeting those goals are literally the ones who are left out of learning,” she said.

Consistency is goal

The changes will actually cost the district more, said Shannon Thompson, dean of academics for Moore Public Schools. The district reported receiving $4.5 million in state and federal funds for gifted education but spent $4.8 million on salaries for teachers in Search, pre-Advanced Placement and Advanced Placement this year.

Implementing STEAM will cost an additional $1 million.

With that program, Moore schools hopes to increase consistency across the district, Thompson said. Currently, Search is offered at 11 school sites and students at other sites are transported to those schools, but STEAM will be held at each elementary site.

“We believe this serves the gifted population and the regular population much better,” Thompson said.

District leaders are also using STEAM to standardize the curriculum. Because Search teachers have had the autonomy to create their own curriculum, some classes focus more on technology and others on humanities. STEAM classes will be the same at each site and area provided by Project Lead the Way, a program used in schools across the country to teach students in-demand skills in computer science, engineering and biomedical science.

“You wouldn’t want your best basketball player sitting on the bench,” Potter said.

Potter’s students at Fisher Elementary build wind turbines, debate at the State Capitol, research robots and compete in a fashion design challenge culminating in a real runway show.

The two-and-a-half hours allotted for Search make these projects doable, she said, whereas it will be very difficult to tackle a complex project in a 45-minute STEAM period.

“It’s not that we don’t want STEAM,” said Potter, who is resigning from the district due to the changes. “There should be both.”

Megan Baxter, whose daughter Abigail is in Search, is upset about the district’s decision to cut the class but keep the funding. She said Abigail’s regular fourth-grade classroom has 24 students this year, making it practically impossible for the teacher to conduct the types of specialized and engaging projects she does in Search.

“The only homework my daughter has is reading. When she goes to Search … it’s helping prepare her for higher-level thinking,” she said. Taking away the program is “not fair to these kids,” she said.