The battle over Classen SAS High School and Northeast Academy grabbed most of the attention during the June 10 Oklahoma City Public Schools board meeting, but new, complex challenges were also revealed. The Board heard a Planning Department report on the number of OKCPS graduates who require remediation in college.

These sad outcomes, as well as new disclosures on the need for the district to take over Seeworth Academy, an alternative school, should prompt an open, evidence-based discussion of complex education policy dilemmas. If we needed more proof, the reorganization of the OKCPS administration was announced only a week later.

OKCPS has plenty on its plate, but I believe the district won’t improve without engaging in transparent, research-based discussions on what it will actually take to provide our kids with the education they deserve. Below is my advice.

Good news, bad news

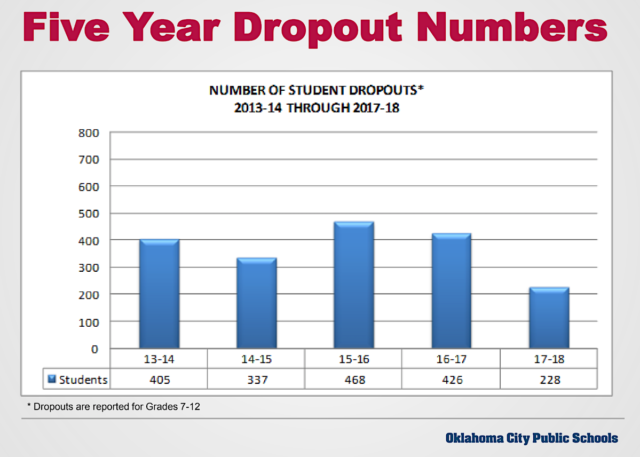

First, the good news is that the OKCPS dropout rate has fallen, down to less than 2 percent in 2017. (See the PDF embedded below.) The bad news is that the use of “credit recovery” programs, across the nation, means we can’t tell how much of the decline is due to real improvements and how much is due to “passing kids on,” regardless of what they haven’t learned. The worst news in the recent OKCPS report is that nearly two-thirds of OKCPS graduates who attend college need remediation.

Since 2002-03, the college-going rates, with or without remediation, have improved for south OKC neighborhood schools and for application schools, both magnets and charters. The biggest declines in college readiness were at Northeast Academy and my old school of John Marshall. To achieve equity, we must evaluate education research and the lessons that should have been learned since the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.

In 2002-03, Northeast was a great application school. It had 847 students, with nearly 57 percent being low-income. Only 19 of its 64 graduates who attended college required remediation. By 2015-16, only 33 Northeast graduates attended college, and two-thirds required remediation. I can’t explain why that excellent school declined. Based on what I witnessed among my young neighbors in OKC’s Central Park neighborhood, I suspect Northeast lost the competition with Harding Prep and Harding Fine Arts for top students. I’m also open to claims of Northeast and other enterprise school supporters who say the OKCPS central office didn’t honor the autonomy that enterprise schools were supposed to be granted.

John Marshall High School ‘flourished’ before NCLB

By 2002-03, John Marshall was the most improved high school in the district. JMHS’s low-income rate declined to about 63 percent and was one reason for increased student performance, but the school’s percentage of students on special education IEPs was nearly 22 percent. This school of 906 students sent 72 graduates to college, with 23 needing no remediation.

Those numbers don’t convey our students’ inspiring accomplishments. During MAPS for Kids, they hosted and advised a couple dozen of the city’s movers and shakers. Ask any of our influential guests and they would praise our kids’ awesome wisdom, how they “worked hard and worked smart” and how they mastered meaningful college preparatory insights.

JMHS flourished as it was granted autonomy. We were allowed a modest measure of authority for enforcing our code of conduct and attendance policies. The students saw our higher standards as an expression of respect for their minds.

Due to NCLB, however, Marshall was then denied the right to enforce attendance and discipline policies. The new priority was “juking the stats,” dropping absences by the hundreds and using credit recovery to improve graduation rates. The students’ name for credit recovery was “exercising the right click finger.” They knew that it made attendance in class optional. Most still came to school as much as before, but dozens of kids just “walked the halls” continually, knowing their misbehavior would be ignored and they would be handed an unearned diploma.

Within a year, Marshall lost a dozen great teachers and an outstanding principal. Eventually, it was divided into the new John Marshall and Centennial. Together, in 2015-16, those two schools sent 51 graduates to college, with all but 14 of them requiring remediation. So, the number attending college without remediation dropped from about one-third to one-fourth.

School autonomy worth valuing

That leads to OKCPS’s second emerging challenge now — Seeworth. I taught for a semester at Seeworth, and I’m not surprised about the allegations against its special education program. I believe dynamic leaders like the school’s founder, Janet Grigg, are the ones who most need checks and balances, but the charter governance system prevented the policy conversations that were needed. I resigned after a disagreement over policy, but it must be remembered that Seeworth had some bright spots.

I hope OKCPS will listen to Seeworth educators’ insights into what it takes to maintain safe and orderly environments. Unlike Seeworth, OKCPS has traditionally ducked the challenge of managing cell phone misuse, and it needs to learn about how to intervene early in disputes so that routine disruptions don’t spin out of control.

Third, some good things will likely happen owing to the new OKCPS administrative reorganization. Probably the best thing in the plan is the commitment to partnership to help “bring trauma-informed practices into our schools.” The reorganization could help recruit new talent, as well as liberate today’s administrators confined by outdated structures. It will be much harder, however, to find talent with significant inner-city experience.

And that brings us back to the common threads in the failures and successes described above. In each of those debacles, sincere people with skin-deep understandings of urban challenges proved the dictum, “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.”

Whether administrators imposed hurried shortcuts like online credit recovery or micromanaged instruction in the search for improved metrics, they ignored the teachers’ and students’ judgements. Second, whether in application schools or neighborhood schools, success requires safe and orderly structure. So, why not grant that autonomy to schools serving our poorest children of color?

OKCPS Dropout statistics

https://nondoc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Dropout-2017-18-and-remediation-rates-2016-17.pdf” height=”450px” download=”all”]