As a regular routine, Sky Easley gets up at 5:50 a.m., brushes his hair and teeth, eats a block of cheese for breakfast and hops on his bike for a 19-minute ride to a “work crew” meeting at Northwest 4th Street and North Walker Avenue.

Easley, 23, and other individuals meet four days a week as part of work crews who do jobs in Oklahoma City, Moore and Edmond. What they and Easley all have in common is a criminal record.

“I need something,” Easley said. “Or I’ll probably be going back to jail soon.”

Easley is working through the Center for Employment Opportunities, a national organization that helps anyone with a criminal record who wants to get into the workforce by providing a temporary, part-time job. CEO also offers coaching to help turn participants into full-time employees elsewhere.

Samuel Eagleson, CEO’s Oklahoma City director, said the organization will work with anyone coming out of incarceration and reentering society, no matter how long they were incarcerated.

“What makes CEO interesting (is) we have such a wide range of participants,” Eagleson said. “We might have someone that’s 18 years old, was in there for two days and had a scare, and now they are ready to get back on their feet. We might have someone who just got out for the first time since 1980.”

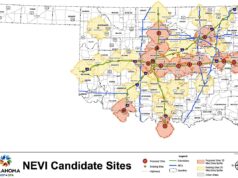

CEO’s Oklahoma City center has six work crews and is partnered with OKC, Moore, Edmond and the Oklahoma Department of Transportation. Crews perform tasks such as clean up and lawn improvement, Eagleson said.

“We typically take on the highest-risk population — over 50 percent of the participants, historically, in Oklahoma City have had no work experience, no high school diploma,” Eagleson said.

CEO offers ‘immediate money’ and guidance

Participating in CEO for the first week often entails meeting to make assessments on where someone stands in the process of getting back into society.

“The first step is to do a four-day orientation called at ‘Pathway to Employment,'” Eagleson said. “We bridge some minor behavioral and skill gaps. We do some vocational training, very minor, learning how to answer the conviction question, but most importantly we are getting them ready to work because by day five, they actually become part time employees with us.”

After those first meetings, administrators determine if participants can go through the process of getting an interview for a full-time job or whether they need to join the work crews first.

“There is no timeline. It’s not five months, six months, one year — we work with them wherever they’re at,” Eagleson said. “So you might come to the office, and we might be able to place you right away, or you might come in and we might have you for eight months. And so it really depends on the person’s situation. We try our best and get them to wherever they need.”

Karl Willet, CEO’s OKC senior site supervisor, said while the crews work five days a week, each participant will have a set day where they come in for meetings with job coaches and to continue assessments.

If for any reason participants are not following through with the program, penalties exist but no one will be counted out.

“They aren’t showing up on time, their supervisor does get back in front of them and they engage in coaching, mentoring and try to talk to them about obstacles,” Willet said.

To keep participants engaged and knowing how to be marketable in the workforce, they meet with job coaches whose specialty is connecting people to community resources and eliminating any barriers that could hinder participants from finding a job.

“Once those things are figured out, we take the assessment again, and you might be job-start-ready this time,” Eagleson said. “If you are job-start-ready, you meet our businesses account manager, and those are employees who actually have relationships with employers.”

Once a participant leaves CEO for a job, they will continue to be checked on for a year to make sure no other “barriers” arise in their lives, Eagleson said. Monetary rewards are provided for staying employed. However, even after participants get a full-time job and leave the program, they will always be welcomed back if anything was to happen. Eagleson said.

For many participants, the program has been a blessing.

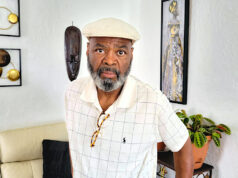

Milton Williams, 58, was sentenced in 2002 to 30 years in prison for possession of a controlled dangerous substance with intent to distribute. He served 17 of those years and is now on parole.

It was Williams’ parole officer who referred him to CEO, and Williams calls it a plus.

“It’s hard coming out of the penitentiary. You don’t have transportation, and a lot of places don’t want to hire you because you might have a theft case or drug case,” Williams said. “And they don’t want that type of person around their business.”

At CEO, daily paychecks are given out to make sure money earned is available quickly, Eagleson said.

“We understand when coming out of incarceration that immediate money can be the difference between you falling into a trap or being able to move forward on your journey,” Eagleson said.

For Williams, that was important.

“Basically, you come out of the penitentiary and you go into the streets, and for a lot of people the streets is what got them into the penitentiary in the first place,” Williams said. “It’s a dead end.”

The wages Williams earns are money he can use for a room and food.

Down but not out

As of now, Easley had been released from Lawton’s halfway house for just over a month. He was first held at Lexington Assessment and Reception Center on a five-year sentence for felony assault with great bodily injury from 2017, but he was transferred to a halfway house, released after two years and is currently on probation for another year, Easley said.

But that wasn’t his first felony. In 2014, when Easley was 18 years old, he was charged with second degree burglary and served about a year in what Easley called a “boot camp”

But once, Easley was accepted into CEO’s program, he “fooled around” for a bit and missed a day of work, he said. But the the coaches in the program still reached out to him.

“I didn’t call in or nothing. So they called me. ‘You have an unexcused absence. Just wondering if you are still wanting to do this program,'” Easley said. “When I thought about it, I just kind’ve thought it was irrelevant. At the time, I didn’t really want no money. I didn’t care at the time. But now I need my money so I can pay bills.”

Right after he got released, it was Easley’s friends that he relied on. Easley said that he hasn’t spoken to his family since the assault charge, mainly because the assault causing bodily injury was to his grandmother.

Easley said he was born with severe ADHD and bipolar disorder, meaning he took multiple medications so he could be “level minded and fit in at school.”

“I couldn’t tell you a single thing any teacher ever told me,” Easley said. “Because they could be talking directly to my face when I was a kid, but I just wouldn’t be able to grasp it because my ears wouldn’t listen.”

Easley described moments as a child where it was difficult for his family to get him to calm down or even go to sleep. He said he had been admitted to St. Anthony Hospital a couple of times for mental health episodes.

But in high school, Easley said he developed a brain tumor in his right frontal lobe. When he had surgery to remove it, Easley said he couldn’t return to school and was taken off his medications.

Easley said his basic understanding of the situation is that he was told he could no longer legally be given psychiatric medication owing to the surgery.

The day of the assault, Easley said he was already “on edge” before his grandmother hit him in the back with a bat.

“My grandma hit me with a bat, and before I could even think, I turned around and punched her,” Easley said. “I reacted and lost my temper. Then she told me to leave and to never come back. And so I did — I took off walking.”

Promising ends

Right now, Easley doesn’t know when he will be ready to reach out to his family.

“It’s like a mental block. Every time you try to think about it, you just run into a wall,” Easley said. “I’ll probably give myself some time. And I’ve already gave myself enough time. It’s just like a 19-minute bike ride. I’m trying to figure out my old route.”

Easley said he wanted to be like his dad’s side of his family who were “a bunch of medics.” But he said he understands it will be a long time until that can happen.

“I knew what I wanted, once upon a time. But I don’t anymore because I’m a felon,” Easley said. “I wanted to be a nurse. I know I can still be a nurse (…) but by that time I’ll be 30 years old. I really don’t see it no more.”

But now, Easley says he is a lot more calm. For his future plans, he said he wants to be an automotive technician.

“Putting motors together, brand stinkin’ new,” Easley said.

If Easley is able to get off probation in June 2020, he said he would like to go to Arkansas and see his father, who used talk to “all the time, but not anymore.”

For Williams, he has already been signed up for multiple job full-time interviews. It is unknown yet if he has been accepted for any of them, but it is something he said he always looks forward to.

Williams said he is already a licensed carpenter, and even though he is spending four days a week weed-eating and may not end up in a carpentering job, the jobs he is doing now will help him find a better one later.

“The jobs that we are finding them for full time employment don’t match what the transitional jobs are. So you might be on the Moore crew weed-eating a park, but when you come into the office for employment meetings, you might be preparing to be a medical coder, you might be preparing to be customer support,” Eagleson said. “The jobs that are on the crews we understand aren’t maybe the most glamorous jobs for everyone, but it is immediate employment that we can guarantee, and if you are coming out of incarceration, you have a felony on your record, you can’t (otherwise) guarantee that direct employment.”

(Correction: This post was updated at 9 a.m. on Sept. 25 to reflect the correct name of CEO’s four step plan.)