Max Bear peered down at the red earth, moving carefully. He was searching for signs of his ancestors’ presence in the shells and beads that had found their way to the surface from a century-old gravesite.

Bear, director of the Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes Historic Preservation Office, had been going about his daily routine in January when he received a call from a tribal member about the items seen at a potential oil well site.

This story was reported by Gaylord News, a Washington reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Oklahoma. This series entitled “Exiled to Indian Country” details the stories of how each of Oklahoma’s 39 tribes ended up in the state.

The caller thought it possible that the land was part of an old gravesite, so Bear and his team went to check it out. With the help of archaeologists from the oil company and the use of ground-penetrating radar technology, their suspicions were confirmed.

Today, the site sits a few miles from Bear’s office in Concho and is marked with a wrought-iron fence, finished in August, to honor those who were buried there, and to prevent any damage to the graves.

“Those are the kinds of things we do as part of our preservation efforts,” Bear said.

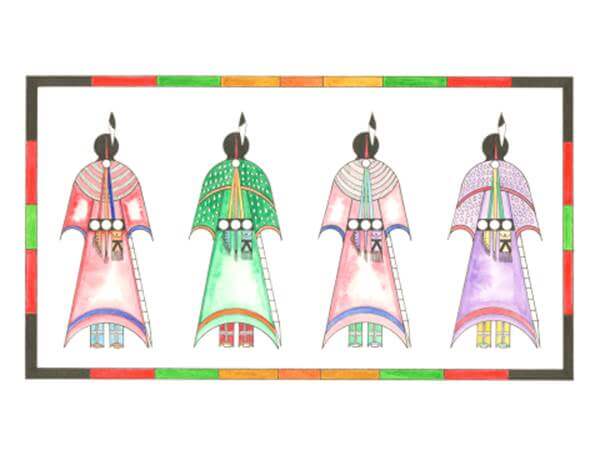

Though federally recognized as one tribe, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were once distinct nations that called lands far from Oklahoma home.

Both were Algonquian-speaking, agricultural people residing in the Great Lakes region along the Mississippi River. The two tribes spoke similar languages, but each had their own unique culture.

Eventually, both were pushed out of the area and adopted the breeding and herding of horses, becoming nomads who followed the buffalo. The two likely came together in the late 18th or early 19th century.

Gordon Yellowman, one of the tribe’s 44 peace chiefs, said it’s difficult to put a date on when the two tribes first came in contact.

“I think we started encountering one another because we were always together closely from our origins,” Yellowman said. “As far as starting out and origin stories, history, where we came from, how we believe this earth was made, our stories are similar.”

The tribes camped together and battled common enemies, but preserved their own languages and traditions, Yellowman said. Also around the 19th century, the Cheyenne and Arapaho each split into two groups: Northern Cheyenne, Southern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho.

After continually being pushed from their homelands and signing multiple land cession and peace treaties with the U.S. government, the Cheyenne and Arapaho experienced a day that changed everything.

Sand Creek Massacre

On Nov. 29, 1864, a band of U.S. soldiers attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children and the elderly. It became known as the Sand Creek Massacre, and the National Parks Service describes the day as “eight hours that changed the Great Plains forever.”

Maj. E. W. Wynkoop investigated the incident and wrote a report including his interviews of the soldiers, who agreed that the violence was atrocious.

“Women and children were killed and scalped, children shot at their mothers’ breasts,” Wynkoop wrote.

After the massacre, outraged Cheyenne warriors carried out a series of raids on the U.S. military, Bear said.

In the fall of 1865, the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho tribes, along with the Comanche, Kiowa and Plains Apache, signed the Little Arkansas Treaty, which gave them land in Kansas and Oklahoma. However, the Little Arkansas treaty was only in effect for less than two years and much of the land it promised was never actually given to tribes.

Finally, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were forced into Indian Territory by the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867. Many died on the journey from disease, Yellowman said.

“There were many of them that fought to stay where they were,” Yellowman said. “But in the end, they lost their lives through that fight. And then when they were marched here forcibly, there was sickness, disease that the whites brought us. Our immune system couldn’t adapt to those diseases, and that’s what killed us off on the way here.”

The treaty created the Cheyenne and Arapaho lands in Oklahoma, with the capital in Concho, and the two eventually became known as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

Through it all, the tribes have held onto their histories and cultures.

One example is the 44-chief system, given to the Cheyenne by the prophet Sweet Medicine. It is said that Sweet Medicine went into a sacred opening at Bear Butte, a mountain-like feature in South Dakota, and returned with rules for the Cheyenne to live by, as well as prophecies predicting the coming of the white man.

The Council of 44 is a group of chiefs who are in charge of keeping the peace within the tribe and taking care of the women, children and the elderly, Yellowman said. Though being on the council is not hereditary, Yellowman’s father and grandfather were both chiefs.

“When I was taken in as a leader, the older chiefs (…) taught me how to do things, how you’re supposed to serve your people,” Yellowman said. “You’re supposed to assist the elderly, assist the children. And most of all, you’re supposed to look out for the infant children that are abandoned or orphaned.”

Another important part of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes today is storytelling — recalling the oral histories of the people and passing them from one generation to the next.

In order to be part of, and keep alive, a “living, breathing culture,” you need to know your people’s history, Yellowman said.

“You have to keep the stories because they’re a part of your identity, of who you are, where you came from, and where you’re going,” Yellowman said.