CLINTON — As the hot evening sun began slanting over the Clinton Police Department headquarters Saturday, hundreds of protesters chanted “all lives matter when black lives matter” while marching through town to protest police brutality and racial inequality.

A few people had gathered in an empty lot across the street from the police station to wait for the marchers to arrive. A young woman named Vanessa Aguirre said the protest had been a big topic of conversation all week at the barbershop where she works.

“It feels like being a part of history,” she said.

Andy Williams, an African-American man who offered to talk about “anything but my age,” said he grew up in Clinton and had seen nothing like the rally in his hometown since the 1960s.

“I love it,” he said. “It’s bringing people together. Not just black people but everybody, so we can stand up together.”

National events touch local wounds

Similar protests have been happening across the country in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, a black man in Minneapolis who died May 25 after a police officer knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes during an arrest.

While the most visible marches have been massive gatherings in larger cities, such as Minneapolis, New York and Washington D.C., protests have also sprung up in many smaller towns. Clinton, which lies about an hour and half west of Oklahoma City, has a population of around 9,000.

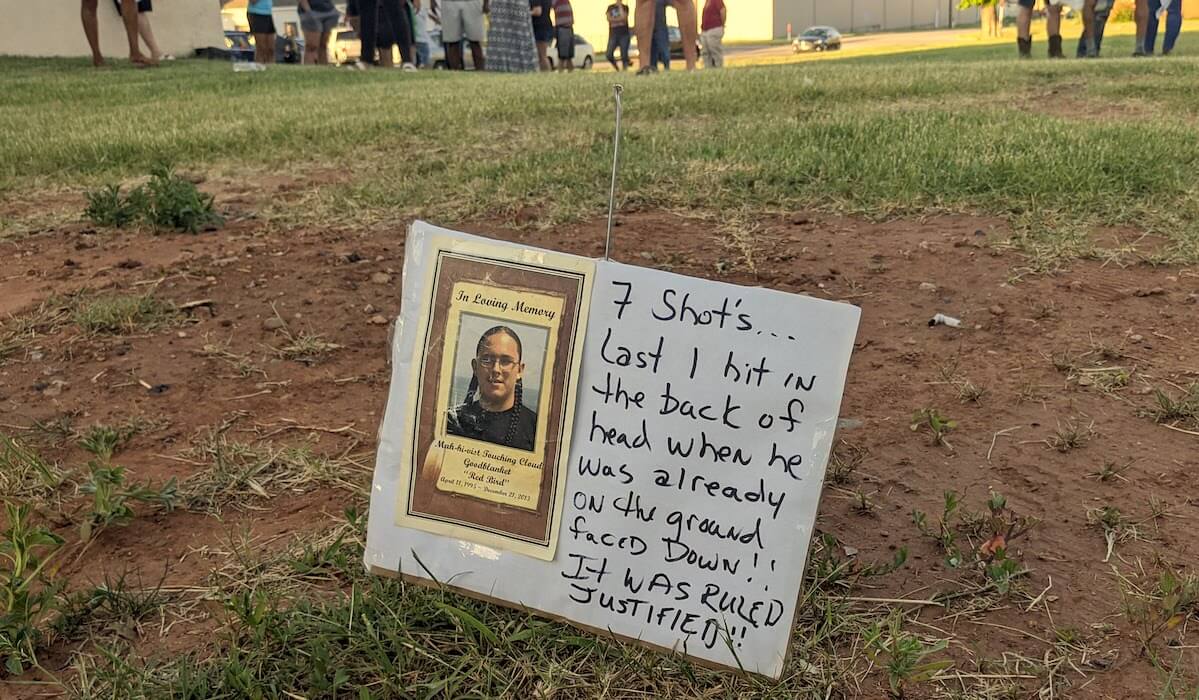

The Clinton march followed in this larger, national movement, but it focused on local tragedies. Many of the marchers held signs and wore shirts commemorating Mah-hi-vist Goodblanket (whose first name translates to Red Bird in English), a Cheyenne-Arapahoe teenager who was killed by Custer County sheriff’s deputies in December 2013.

Goodblanket, who had been diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder, was shot after his parents called 9-1-1 because he was having a mental episode. The shooting was ruled to have been justified and the officers were later given an award for their response to the call.

Goodblanket’s cousin, Danielle Goodblanket-Cling, carried a portrait of Mah-hi-vist with her at Saturday night’s march.

“I’m emotional,” she said. “It feels like it happened yesterday.”

Goodblanket-Cling has always lived in the area and said she was surprised and pleased by the turnout. She said she has spent much of her life feeling nervous about coming to town and what might happen if she ever got stopped by law enforcement — a feeling made worse by her cousin’s death.

“The Goodblankets mostly keep to ourselves since we lost Red Bird,” she said.

She said her fears have subsided a bit in the past few years, as activism related to her cousin’s shooting has spurred some conversations with local authorities, but the family is still hoping for the case to be reopened.

‘White bones, yellow marrow and red blood’

As the marchers arrived at the empty lot, a couple of police officers met them with boxes of pizza, which were passed around as the protesters gathered to hear a number of speeches. Clinton’s mayor, David Berrong, was in the crowd, and someone said they saw the police chief there, too.

Among the speakers was T. Sheri Dickerson, the director of the Oklahoma City Black Live Matter chapter, who called for the white people present to “embrace discomfort” and to “lift up” those affected by racism.

She also mentioned that she, personally, wouldn’t eat pizza brought by police.

“I have trust issues,” she said. “Which are justified.”

Dickerson introduced Melissa Goodblanket, Mah-hi-vist’s mother, Melissa Goodblanket, who gave an emotional speech about the loss of her son. She called for the current justice system to be “dismantled,” but she also called for unity.

“We’re all the same,” she said. “We’ve all got white bones, yellow marrow and red blood.”

Solidarity between black and Native American communities and the need for better mechanisms to respond to mental health crises became recurring themes at Saturday’s rally. (According to a CDC study from 2017, Native Americans are killed by law enforcement at a higher rate than any other population in the country, followed by African-Americans.)

Several speakers and attendees mentioned the death of Benjamin Whiteshield, another Native American man who was shot and killed by a Clinton police officer in 2012. Whiteshield’s family had driven him to the police station because he was having a delusional episode.

A woman named Nicole Barker told the crowd about an incident from earlier in the day. She stopped to help a woman by the side of the road after realizing it was a cousin of hers who lives with mental illness. The cousin ended up pulling a knife on her, and Barker called the police.

“I said, ‘My cousin needs assistance,'” she said. “Like all black people have done, I said, ‘Please don’t shoot my cousin. Please don’t shoot my cousin. She just needs help.'”

By the time the police arrived, the two women were struggling on the ground, and the police pulled their guns.

“It was the first time I’ve had a gun pointed at me,” Barker said.

Barker became emotional as she told her story, at one point doubling over and crying as people in the crowd called out encouragement.

She said she shouted at the police not to shoot, and they put their guns down.

“They did everything right,” she said.

Barker said police asked if she wanted to press charges. She told them she didn’t and that her cousin just needed help.

‘Everybody’s so scared’

The march in Clinton was organized by a woman named Jennifer Barron, who goes by Juju. She was inspired by the protests she saw happening all over country, even though she hadn’t done any similar organizing before and found that there wasn’t much structure in place for doing so.

“Everyone’s so scared about the police, because everyone’s related. So people do get scared sometimes because they don’t want to push the wrong buttons,” she said.

At first, she had a hard time getting people to agree to speak at the rally because they were scared of police harassment.

“They work at schools, at the police, they know them,” Barron said. “It’s a real small town, so everybody knows everybody.”

But Barron said that once the organization of Saturday’s event was underway, she found the community supportive. Even Clinton Police Chief Paul Rinkel was encouraging, she said.

In recent years, the shootings of Goodblanket and Whiteshield had a chilling effect on the town, she said.

“I was scared of getting pulled over,” Barron said. “I was actually really scared of getting shot because I was Native American.”

She hopes the rally will help change the atmosphere.

“I just want all the kids and everybody to know that it’s OK to be a minority here,” she said. “That it’s OK to be proud of your tradition and your heritage.”