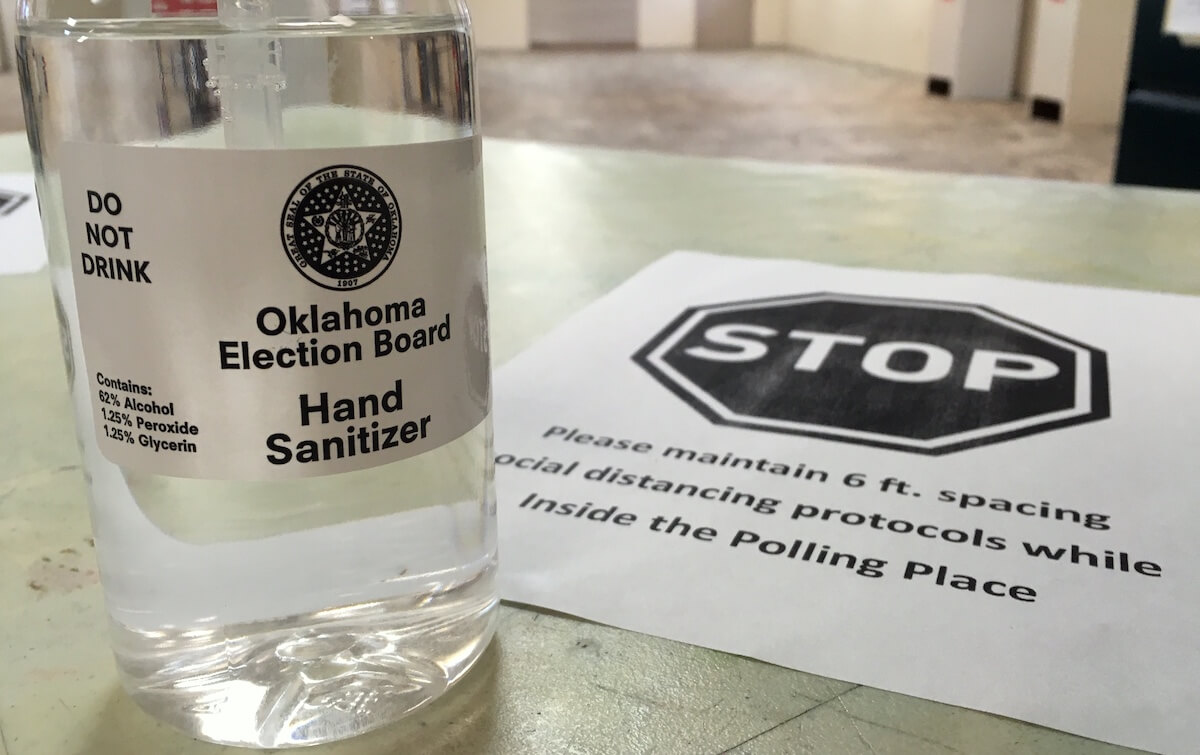

The rituals of working an election are familiar to many poll workers: tear “I Voted” stickers off the roll, set out a big stock of pens, tape the sample ballots on the wall.

I’ve served as a poll worker in half a dozen elections, starting in 2016, and it’s always heartening to be among these small signs that the engine of representative government is kicking into high gear.

This year, however, the procedures were more involved: masks, Oklahoma Election Board-branded hand sanitizer and tape demarcating six-foot increments.

But despite the pandemic and its accompanying social upheaval, in Oklahoma County alone 220 of the folks checking voter names in the precinct registry and handing out ballots were first-timers, according to Toni Culpepper of the Oklahoma County Election Board.

“I was a little shocked myself that we had so many,” Culpepper said.

To hear a few new poll workers tell it, we have COVID-19 and social media to thank for this uptick. The economic disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic left more people free on a weekday, and the surging ubiquity of political chatter on social media left more people looking for hands-on civic engagement opportunities close to home.

To sign up to serve as a poll worker, contact your county election board.

Poll workers do the on-the-ground work of making elections happen, and yet, in discussions of election security and stability, the need for a strong and diverse pool of poll workers is rarely discussed. According to the Pew Research Center, the majority of poll workers in the U.S. are over 60. The COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the need for younger people to step into these roles.

Likewise, older Americans tend to vote at much higher rates than their younger counterparts. Current efforts to increase the number of younger poll workers emphasize the hope that giving people a glimpse into the heart of our electoral system will encourage them to show up on the other side of the voting booth as well.

First-time poll workers see how the sausage is made

Well into college, Avery Stevens, who is now 28, wouldn’t have said she was “into politics.” She had strong opinions and cared deeply about the people in her community, but only in more recent years has she made the connection between that care and ongoing civic engagement, such as voting in primaries and truly paying attention to local politics.

She and her husband had been serving in the Peace Corps in Armenia when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and they returned to Oklahoma ready to channel their energy into their local community. Stevens found a job as a high school theater teacher, which she’ll start this fall, but in the meantime she’s looking for other avenues.

She learned about the Oklahoma County Election Board’s need for additional poll workers on social media when OKC Ward 6 Councilwoman JoBeth Hamon posted about it.

“I don’t think I would have known about it if she hadn’t posted that,” Stevens said. “One reason I was able to do it was because I wasn’t working (…) but in the future I’ll probably not be able to do it because I have to teach on Tuesdays.”

Stevens was serving as an emergency poll worker, meaning she received training online shortly before the election and would fill in staffing gaps wherever needed — a particularly crucial task in this election cycle, as some older workers stayed home in order to limit their risk of exposure to COVID-19.

Poll workers are traditionally trained in person and recertified by another round of training every three years. County election boards staff elections by sending assignments to their pool of certified poll workers in the month before the election and confirming that those folks are available to work.

Stevens completed an online training and, at 6:15 on the morning of the June 30 primary election, she reported to the Oklahoma County Election Board and waited under the fluorescent lights to see where she would be assigned.

After about an hour, as other emergency workers were given assignments and sent on their way, someone in the room asked “What do we do?” and an Election Board employee replied, “If you have a book, read. If you have a phone, play. (…) You’re here as an emergency person if needed.”

By 9 a.m. Stevens was one of a dozen people who had yet to be assigned to a precinct, and the mood in the waiting room was like a game show, with an election board employee periodically entering the room to give a polling location to a lucky volunteer.

After another hour of waiting, and swinging by her own polling place to vote — since the online training hadn’t made clear that poll workers needed to vote early or vote by mail — Stevens arrived at her assigned polling location, in Midwest City. There, she got to try her hand at being an election judge, which is the title of the person who looks voters up and has them sign the precinct registry. She also got to serve as a clerk, which is the title for the person who hands out ballots.

Royce Sharp, another first-time emergency poll worker, was one of the first people out the door of the Oklahoma County Election Board on the morning of the election. Sent to Church of the Open Arms on North Pennsylvania Avenue, Sharp spent his first day as a poll worker serving as an inspector. Inspectors are charged with picking up and returning all the voting equipment to their County Election Board. They are the top brass of the poll worker hierarchy and are paid a bit more for the trouble: $97 for the day, compared to $87 to to be a clerk or a judge.

Like Stevens, Sharp, a 37-year old documentary filmmaker, said the coronavirus pandemic played a role in his decision to volunteer.

“Normally I’m traveling, but thanks to coronavirus I’m able to help out,” he said, adding that he knew the average poll worker is older and more susceptible to the virus, so he thought it would be helpful if young people stepped up.

“All the cool kids were doing it,” he joked.

Sharp was “pleasantly surprised with how efficiently run our elections are.” He said working the polls gave him a glimpse into the nitty-gritty details of the electoral process, from security procedures to the convoluted ways voters navigate a rule banning partisan or political talk in polling places.

But he said the biggest takeaway for him was the need for young people to participate in elections.

“Young people need to be way, way, way more involved in the electoral process, from top to bottom,” he said.

Stevens said she was impressed by the diversity of the turnout at her polling station, but she also noticed that young people were underrepresented among both voters and poll workers. In the waiting room at the election board office, she said she was one of only a handful of people who appeared to be younger than 50.

Serving as a poll worker brought Stevens a fresh appreciation of the importance of elections. She said she believed others could benefit from the experience as well, as seeing the process first-hand “would make people more aware of elections and may help people find them more important.”

Efforts to involve young people look to the future

The value of this insider experience is not lost on advocates seeking to expand the pool of eligible poll workers. Oklahoma currently allows only registered voters, who must be at least 18, to become poll workers. But a group of advocates including the Oklahoma Public School Resource Center and Generation Citizen are pushing for the Oklahoma Legislature to take up a bill in 2021 that would make high school students eligible to serve even before they are eligible to vote.

The proposal would allow students who are sponsored by a teacher to be trained as student poll workers and to receive school credit for the experience.

And there are positive indicators that making teenagers eligible to work elections could have a positive impact on voter turnout in the long term.

In a 2018 report, the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University polled 1,127 people age 18-34 and found that one barrier to young voter turnout was that only 13 percent of respondents had seen a young person working at their polling place.

Expanding poll worker eligibility could elegantly address two problems with one solution.

First, as the pandemic has made clear, we need a large, adaptable pool of poll workers to ensure the secure and efficient functioning of our elections. Young people may not be the most resilient group in the face of every social challenge, as they are with COVID-19, but diversifying the age of our poll workers would certainly make the system stronger.

And, second, as overall voter turnout among young people remains painfully low, offering a hands-on civics education to high schoolers has the potential to improve the understanding of the election process among young people, which in turn could help turn those young people into regular voters for years to come.

There are other hopeful signs about the future of voting in Oklahoma. Nearly 675,000 Oklahomans cast ballots on June 30. That’s a roughly 25 percent decrease from the more than 890,000 voters who came out for the 2018 primary (a turnout attributable to the gubernatorial primary and SQ 788, which legalized medical marijuana). But Oklahoma’s 2020 primary numbers were a huge improvement over the turnout in the 2014 Primary, when only 432,757 votes were cast.

Although our political life is contentious and volatile, voter turnout could also be on the rise in Oklahoma because day-to-day political engagement is becoming normalized.

That is certainly true for Stevens, and it played into her decision to serve as a poll worker.

“I’m trying to push myself to do more, ” she said. “It’s becoming harder and harder to ignore that you need to be a part of this.”