(Editor’s note: On Aug. 6, 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in the class action suit mentioned in this story that PACER fees have been inflated to include costs for items unrelated to the upkeep of PACER, such as courtroom televisions and computer systems used to manage jurors. The suit called for excess fees to be refunded to those who used the site from 2010-2016. As of Aug. 7, it is unclear what the amount of those refunds would be, if current PACER fees will be lowered or if the government will appeal the decision to the full Appeals Court or the Supreme Court.)

PACER, a government-run service that provides the public with access to federal electronic court records, has long been criticized for its inefficiencies, outdated interface, missing cases and, according to an ongoing class-action lawsuit, exorbitant fees.

On June 28, PACER launched a new website, its first major update in more than a decade. The new, modernized site is intended to make the system easier to navigate and more accessible, and it includes explanations of how to make a search. The site also began to collect analytical data to be used for future improvements.

“We are pleased to release this new version of the PACER website that will enable the public to not only access and use it more easily, but also have a better understanding of the electronic public access services that the Judiciary offers,” Jane MacCracken, programs division chief in the Administrative Office of the U.S. Court Services Office, said in the announcement of the new site.

However, critics of the system say these changes are mainly cosmetic and don’t address many of the logistical and financial obstacles that stifle PACER’s usefulness.

“In general, PACER is a cumbersome, often difficult-to-use system that contains a landmine of fees that all but the most experienced users find difficult to navigate,” said Ryan Kiesel, lawyer and executive director for the ACLU of Oklahoma.

The debate over PACER is also a debate about public access and who should be able to have court data at their fingertips. Right now, Kiesel said, access is functionally limited to lawyers and journalists with experience and institutional backing. Advocates of changes to PACER hope to make these records easily available to everyone.

Public access for a fee

PACER was established in 1988 with the goal of making court records more accessible to the public. In the old days, pulling a court record meant physically going to the courthouse. Now, according to the PACER website, the system provides electronic access to “more than 1 billion documents filed at more than 200 federal courts — nearly all the documents filed by a judge or the parties in any case.”

Though heading over to a federal courthouse is still an option, it is considerably more time-consuming than going online (and of course, requires you to be in the same city as the records you want to access). For an online look at documents in hundreds of thousands of cases, PACER is the only option.

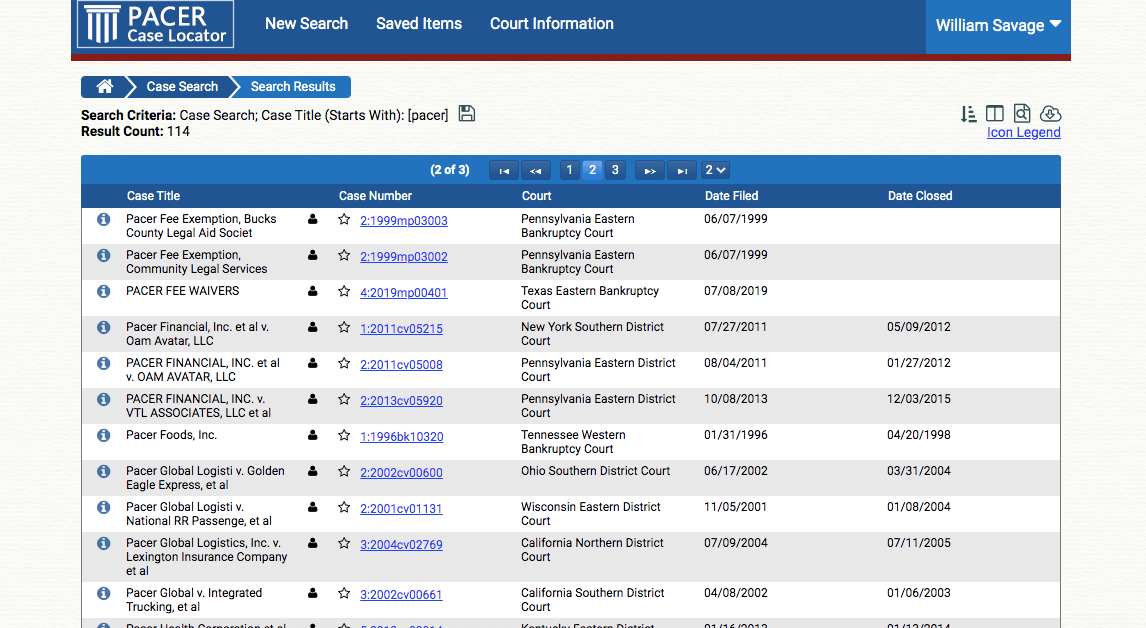

Users must register to access the database and can search within a specific federal court system or through a nationwide index.

There are currently more than 1 million PACER users, including attorneys, government agencies, researchers, educational and financial institutions and journalists. For lawyers, a PACER account is functionally required for practicing in federal court.

But access to these documents is not free. When users conduct a search, they are charged $0.10 per page of search results they access. Access to case information is $0.10 per page, capped at $3 per document. These fees apply even though users do not know how long a document will be before opening it.

Although fees are waived for those who accumulate less than $30 in charges each quarter — which according to PACER’s website is 75 percent of users — searchers rarely know how much they will have to pay. The $30 threshold was instated last year; previously fees were waived only for those with less than $15 in searches.

Law firms often work PACER charges into firm finances or pass them on to clients, meaning attorneys often lack perspective about their PACER use, as they may not pay the bills.

According to the PACER website, the system is funded entirely with user fees and the charges are used to “support the ongoing operations, development, and maintenance costs associated with the electronic case management system and other systems, such as the PACER Case Locator, and is used by federal courts throughout the country.”

In 2017, however, a class-action lawsuit called National Veterans Legal Services Program, et al. v. United States was brought by a group composed of primarily nonprofit organizations, claiming PACER charges more money than is needed to cover operating costs and that the majority of the money is being used for courtroom technology and other projects unrelated to PACER. Charging more than is necessary, according to the plaintiffs, violates the E-Government Act of 2002.

In 2016, PACER collected $146.4 million in fees, according to the Washington Post. From 2010 to 2016, annual expenses for electronic access programs never broke the $25 million mark, the Post also reported.

In March 2018, a judge in the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia ruled that fees collected from PACER could be used for the system itself, other electronic filing systems, electronic bankruptcy noticing, some staffing and training programs and certain telecommunications services. They can not, however, can not be used for most courtroom technologies, web-based juror services or victim notification programs.

Both the plaintiffs and the government appealed the decision. Oral arguments were heard in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in February, but no decision has been released.

To Kiesel, the issue is more than a legal matter. It is a question of whether PACER — short for Public Access to Court Electronic Records — really promotes public access.

“The accessibility of these documents both to the bar and the public should be free and as easy to navigate as possible,” Kiesel said. “If there’s a need for funding to be able to provide these services, that funding shouldn’t come from the backs of fees. It should come from direct appropriations. If you want to find something out about a case that requires you to go on PACER, you shouldn’t have to choose between navigating this system that’s fraught with fees or not getting that information.”

The fees aren’t the only obstacle to accessing court records through PACER. The records from several courts aren’t available on the system, because the documents were incompatible with a software upgrade. And the files that are there can be hard to access.

According to Kiesel, unless you’re a seasoned attorney who uses PACER on a regular basis, the system is likely to be lost on you.

“For the general public, it’s all but impossible to use in an effort to access otherwise publicly available documents,” Kiesel said.

Paying for imperfection

This was one of a myriad of issues Robert Patrick, a federal court reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, hoped to address when he joined a PACER user group that was formed in January to provide feedback on and suggest improvements for PACER. The group, which includes members of the legal profession, media and academics, has met twice, according to Patrick.

Patrick is in his 15th year of covering federal courts in St. Louis, which means he works primarily with documents from two federal districts: the Southern District of Illinois and the Eastern District of Missouri.

“I’m on PACER daily, multiple multiple times a day,” he said.

Patrick said his biggest issue with PACER is technically not about the system itself but the information put into it. For certain types of court documents, including plea agreements, sentencing memos and search warrants, it’s up to the judge or the individual court system to decide whether the information will be automatically sealed, making it inaccessible.

As a journalist, Patrick’s ideal situation would be to have no document sealed unless there was truly compromising or personal information, such as medical records, enclosed. In lieu of that, he said, he’d at least like a standardized system. PACER pulls records from 214 separate federal systems, one for each appellate, district and bankruptcy court, each of which has its own regulations for what automatically becomes public. .

”There are things you can see in East St. Louis that you can’t see a couple of miles across the river in St. Louis because the rules are different from courthouse to courthouse, and it has struck me, as a non-lawyer, as a little bit ridiculous that we all can’t agree on kind of some basic guidelines for what is public and what isn’t,” Patrick said. “Essentially, what I want someone to do is to tell judges all across the country, ‘You have to agree on some basic rules.'”

Variability in rules, according to Patrick, makes an already confusing website even more inaccessible, because people often don’t know what types of documents are even available for a certain court system, especially if they’re used to working within the rules of a different one.

“It’s a real problem, because you have such a patchwork, and so people who are not familiar with the system don’t know what’s out there and don’t know that it’s possible to get some of these things,” Patrick said. “I don’t think it should be set up to be sort of this puzzle you have to solve to be able to get public records, because we all pay for these things already.”

Patrick said he would also like to see more sophisticated search options for the PACER system. For instance, he can’t currently look for all the cases involving a certain charge or all cases filed by a certain lawyer. Patrick said he is more likely to use individual court sites because PACER is often a day delayed, meaning the newest cases can’t always be found.

Generally, according to Patrick, members of his PACER user group have requested improvements in the areas of efficient access and the amount of data available, though criticisms of the pricing structure have also been discussed. The user group’s work, which was delayed by the coronavirus pandemic, is ongoing.

Better together?

Despite his many criticisms, Patrick doesn’t miss the old days when acquiring court records meant walking to a courthouse and hoping you needed the documents during standard working hours. For his job particularly, he said, systems like PACER make it possible to learn quickly about cases around the country that he might not have been able to find otherwise.

This is especially true, Patrick said, given the quality of some state court records systems.

“As much as people complain about PACER, it’s a hell of a lot better than most state systems when it comes to accessing records,” Patrick said. “If you’re popping in to pull one case from Texas, you swiftly realize the benefits of systems such as (…) PACER.”

On the other hand, some states have systems that serve a reminder of what PACER could be.

Kiesel praised the Oklahoma State Courts Network, which consolidates information from courts across the state.

“As a general model, for Oklahoma legal practitioners and Oklahomans in general, we’re fortunate that we have one of the best legal research tools in OSCN in the nation,” Kiesel said. “There’s a little whiplash you get when you’re researching legal matters in Oklahoma to try to access those same legal matters on PACER.”

Oklahoma has three district courts (Northern, Eastern, Western) and is part of the federal 10th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Alternative options setting a new PACE-R

While plaintiffs in the lawsuit await a decision and the working group continues to meet, other PACER critics are working to improve the service however they can — or offer an alternative.

In 2019, U.S. Reps. Doug Collins (R-Ga.) and Mike Quigley (D-Ill.) introduced a bill that would have eliminated the charge to use PACER and would have added a general search function. The bill did not make it out of committee.

Later that year, the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Courts held a hearing on the issue during which Judge Audrey Fleissig of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri said PACER fees could never be eliminated completely.

“Our case management and public access systems can never be free because they require over $100 million per year just to operate,” Fleissig said. “That money must come from somewhere.”

One effort to make the information on PACER more accessible is being carried out by a nonprofit called the Free Law Project. The organization runs RECAP, a browser extension that automatically uploads any document a PACER user pays for and views to a free website for others to access.

“Whenever you do certain things in PACER, it charges you money, and the idea of RECAP is when you purchase a docket or you purchase a PDF or other things, you’ll send us a copy of the thing that you purchase,” said Michael Lissner, executive director of the Free Law Project. “And then if anybody else needs that thing, we will make it available to you inside of PACER itself by providing a link or a little information message.”

The documents are available to be searched on RECAP’s site and have also been made text-searchable, unlike the ones in the PACER system. This has enabled reporting that relies on finding similar text across court documents, such as a recent story by the New York Times that found the phrase “I can’t breathe” used in 70 cases from the past decade when a citizen died in police custody.

RECAP was developed by students at the Center for Information, Technology and Policy at Princeton University. As students graduated and stopped updating the site, the Free Law Project took over the maintenance of RECAP.

“It accomplishes a couple of things,” Lissner explained. “The first is it’ll save you money, and so if someone’s ever purchased anything, you’ll get it for free. That’s cool. And we have millions and millions of documents now. And we haven’t ever tallied it up, but we probably save journalists a couple of thousand dollars every day.”

Documents received by RECAP are also stored on the Internet Archive, which stores the history of web pages and online documents. The project also maintains a forum where users can post problems they find within PACER.

“The other thing that’s really nice is we’re building up a public collection of all the data,” Lissner said.

PACER is estimated to have between 500 million and one billion documents. Lissner said it would cost $1 billion to download all those files. Similar services have been created by others, such as Big Cases Bot, a Twitter account created by reporter Brad Heath that automatically monitors notable cases and uploads files to DocumentCloud when they are released, tweeting a notification to its followers.

These services aim to reduce public access barriers that the PACER system presents. According to Patrick, any system of public records must be accessible to all.

“At its core, the default should be, these belong to you and I, the taxpayers,” Patrick said. “One of the foundations of the American court system is that it is all visible.”

Lissner agrees, and for that reason feels services such as RECAP are short-term solutions. He said the only way to solve the “PACER problem” is to make the service entirely free.

“Permanent solutions are making PACER free. That’s what needs to happen,” Lissner said. “There are obstacles, but they’re solvable.”

The documents contained within PACER are not just relevant to reporters, lawyers or those with active cases, Kiesel pointed out. That’s why he considers easy public access to be crucial.

“There are any number of issues that present themselves in legal filings across the nation that have tremendous consequences on our day-to-day lives, and the public should be able to see these,” he said. “We shouldn’t have to rely on either the legal professional class or the media to be able to access these documents and interpret them for the general public. The general public should be able to go to these documents directly themselves and at no cost.”