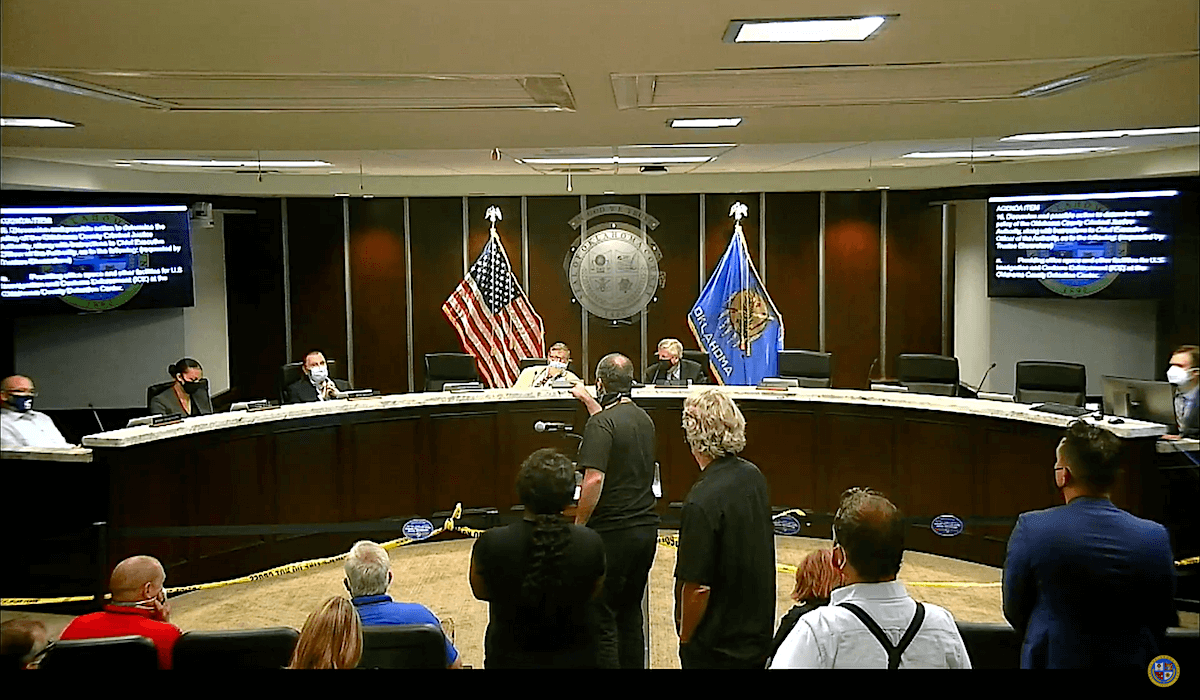

Public meetings are often tedious, sparsely attended affairs, but this past year the meetings of the Oklahoma County Criminal Justice Authority, which oversees the county jail, have become one of the hottest tickets in town.

Beginning last summer, a small cadre of dedicated criminal-justice activists have screamed at, cajoled and urged members of the jail trust (as the body is commonly known) to see things their way on issues ranging from the presence of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents at the jail to what to do with $40 million in CARES Act money allocated to the detention center.

More recently, these activists have had company. At least one man showed up with a Make America Great Again hat while another wore a T-shirt with the emblem of the far-right group the Proud Boys on the back. One of the two used a racial slur while shouting at a black activist who was also at the meeting. A scuffle ensued, and deputies were needed to restore order.

“They were hell, absolute hell,” trustee Sue Ann Arnall said of some of 2020’s jail trust meetings. “No one should have to endure that type of abuse on either side. It was awful. It was personal. However, it has been a learning process.”

Members of the Oklahoma County Criminal Justice Authority, or “jail trust”

Tricia Everest

Jim Couch

Sue Ann Arnall

Francie Ekwerekwu

Kevin Calvey

Ben Brown

Todd Lamb

M.T. Berry

Tommie Johnson**Oklahoma County’s sheriff or a designee serves on the trust. While P.D. Taylor was sheriff, attorney Danny Honeycutt represented him.

This drama — which shows no signs of receding — has unfolded around an organization aimed at making Oklahoma County’s aging and heavily maligned county jail a more humane place to house those who break the law.

The trust assumed oversight of the jail from the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office six months ago, and the results so far are a mixed bag. Some of the trust’s nine members see encouraging incremental improvement. Others think the trust is lagging behind in its mission.

The tumultuous meetings point to a rocky road ahead for the jail trust, as conflicts between its members and overwhelming challenges at the jail itself collide with the vocal presence of local activists.

A history of problems

The Oklahoma County Jail has been plagued by trouble since it opened in 1991. Billed as a state-of-the-art, ultra-modern facility, design flaws were apparent almost immediately. Within the jail’s first half decade, at least three prisoners successfully broke out. One inmate used a spork to chisel away at a window to escape. Another used coat hooks to successfully break through hollow concrete blocks, according to a story in The Oklahoman.

More recently, an inmate used a bed sheet to escape from a 12th floor cell.

But perhaps most disturbing are reports of numerous human and civil rights violations within the jail’s walls, as detailed in a 2008 report by the U.S. Department of Justice. The report outlined issues with overcrowding, staffing and inmate supervision, among other problems. When inspectors visited the facility in 2007 they found more than 2,400 inmates in a facility designed for half that many.

The jail continues to be under oversight of the U.S. Department of Justice, a status it has held since 2009, because of the many violations found in the report.

Inmate deaths have, nevertheless, continued to be a regular occurrence. In the five-year period between 2014 and 2019, 45 inmates died in jail custody.

The jail trust was created in an attempt to improve conditions at the jail. That work has included removing the jail’s day-to-day operations from the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Department and hiring an administrator to carry out the directives of the trust. Those directives have included improvements to plumbing and HVAC systems at the jail, as well as segregating new inmates from those currently incarcerated in an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Summer of controversy

From its very first days of overseeing the jail, the trust has had to operate in crisis mode while also figuring out how to conduct business during a pandemic. The situation has led to confusion and controversy.

In September, for instance, the trust voted 4-2 to remove ICE agents from the jail. But that vote was called into question by the trust’s attorney, John Michael Williams, because five votes are necessary under the trust rules for a vote. During the vote, chairwoman Tricia Everest, who took part remotely, became disconnected from the call.

The issue remains unresolved. Trustee Francie Ekwerewku has said she plans to address it at a future meeting. In October, trustee and County Commissioner Kevin Calvey sued the trust to maintain ICE presence at the jail, but the suit was later dismissed, at Calvey’s request.

In August, after acrimonious debate, the Oklahoma County Budget Board voted to shift the majority of the $47 million the county received from the federal CARES Act to the jail trust, over the objections of County Commissioner Carrie Blumert and others. The meeting at which the vote took place lasted less than one minute, leaving some to wonder if there had been discussion about the issue prior to the meeting, which could be a violation of open meetings laws.

Calvey was the primary mover behind the allocation. He argued that the state had already set up lending pathways to businesses affected by the pandemic, so county CARES money wasn’t needed for that purpose, and there was little demand anyway.

The CARES funds then caused heated debates at the jail trust meetings over how to use the money and whether it should have even been sent to the trust in the first place.

Ultimately, the trust kept about $15 million, which was used to improve plumbing and HVAC systems at the jail, and sent $25 million back to the county, where demand from local businesses was so intense that applications for assistance had to be shut down early.

“The money was gone so fast,” Blumert said. “We had over 800 applications in the first few days. There was a lot of demand. We thought we would have it open for two weeks, and we ended up taking it down on day five.”

Ekwerekwu, who is an attorney with TEEM, an organization that works to break down barriers for those impacted by the criminal justice system, said she thinks the whole process was poorly handled. She said much of the money should have gone to county residents and businesses in need.

“I was blindsided by the CARES Act money being diverted to the jail,” she said. “I had no idea that was going to happen. It took everyone by surprise that it was being orchestrated that way, behind the scenes.”

Ekwerekwu observed that the debates over CARES Act funds and ICE agents quickly became very political, which she believes undermined the mission of the trust.

“Some politics got involved for some on the trust, and I think politics ruins public efforts,” she said. “It’s supposed to be a non-partisan effort. That’s my opinion. Unfortunately, I think people’s political agendas are the driving force of why they are on the trust.”

Attorney fees raise concerns

Not all of the issues facing the jail trust have drawn crowds. Several people have expressed concern about lesser-known aspects of the trust’s management, including the amount of money spent on legal fees.

“I can certainly tell you — subject to whatever billable hours that the lawyers the trust hires are charging — those can be significant,” said Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater. “Good God, I can’t imagine what they are paying some of these lawyers.”

Over the course of 2020, the jail trust spent $237,082 on legal services from John Michael Williams’ Oklahoma City law firm, Williams, Box, Forshee & Bullard, according to records obtained by NonDoc. The firm has negotiated contracts with vendors and has also prepared meeting minutes and agendas.

Williams’ firm invoiced the trust $38,000 in June and another $25,000 in July, which are the two largest single expenditures the trust had all year.

The trust also spent another $41,000 with Oklahoma City firm Gable Gotwals. That firm represented the trust when trustee Kevin Calvey sued it to keep ICE agents at the jail in October. The case was dismissed Dec. 28.

Some trust members have had concerns about so much money being spent on legal services.

“I am concerned,” Brown said. “We’re spending a lot of money on legal fees. I’m not convinced it’s all necessary.”

Ekwerekwu agreed, adding that some of the money could have been used for early COVID-19 mitigation efforts at the jail.

“I think it’s way too much,” she said. “I think Mr. Williams is a great attorney. I don’t doubt that he is compensated that amount of money for the work he does for other clients that he has. But I think it was far too much for this particular job, this cause. I don’t think we should have afforded that much for attorneys’ fees when we desperately needed that money to address issues at the jail.”

Prater noted that his office could have represented the jail trust in legal matters, potentially at a more certain rate than that of a private law firm.

“We were approached to determine if it was lawful for us to represent the trust,” Prater said. “We advised them under circumstances that it was but ultimately the trust decided to hire outside counsel.”

Trustee Sue Ann Arnall attributed the costs to some early missteps.

“I’m hoping we can get that under control a little more,” she said. “Some of it was (the fact it was our) first year. Getting our bearings. We’ve made some false moves. I think as we get more engaged as trust members it will change.”

Williams: ‘We established a new business from top to bottom’

Williams said the fees his firm charged were a fair price for the work he did getting the jail trust get up and running.

“We established a new business from top to bottom,” he said. “It’s an entity that did not exist. Some of the simplest things — like the initial payrolls, certain IRS regulations, routine things like that — are all things that new businesses have to do, and that’s what we’ve been engaged in.”

Williams said his firm has dealt with contract issues ranging from phone service, the jail’s new commissary services and a host of pandemic-related issues, including providing legal input on some of the issues the trust debated.

“We’ve had some diversions,” he said. “In our meetings, we’ve had people who have differing viewpoints and some questions that they have raised, and they want answers to those questions. Then COVID came along, and there were many legal things associated with that.”

Williams said he expected the amount spent on legal fees by the trust to decline in 2021, and he said he hopes to reduce his firm’s involvement in the trust.

“This isn’t a good long-term situation for us to spend as much time as we did in this law firm working on jail activities,” he said. “It’s not good long term for the jail and for this law firm. We’re doing this work at a significantly discounted rate.”

Activists push for reform

As the trust moves forward, it will do so with plenty of scrutiny and vocal feedback from the public. Trust members have been shouted down, cursed at and accused of being racist and incompetent. These disruptions have become a regular feature of jail trust meetings.

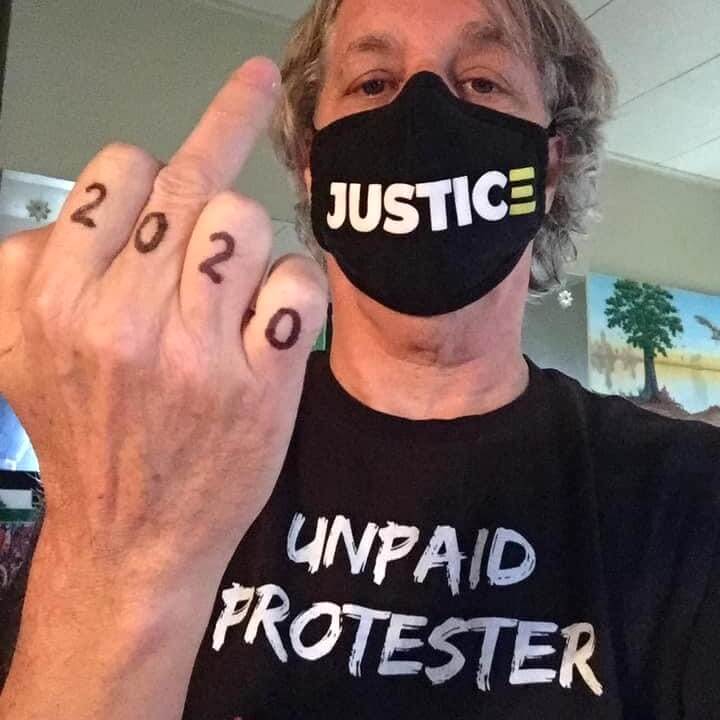

Mark Faulk is among a handful of criminal-justice activists who have regularly attended and sometimes disrupted the meetings.

Faulk has a long history of interest in criminal justice. He’s currently involved in an ongoing documentary film project on the subject, and he believes the Oklahoma County Jail deserves every ounce of criticism directed its way.

Faulk believes the trust’s very existence is illegal because voters never had a chance to select anyone on the trust. He also says most of the trustees lack the knowledge needed for the job.

“It seems like they’re really clueless as to what’s going on in the jail,” he said. “Frankly, I would question their credentials. Two billionaire women and people who don’t have specific backgrounds in managing the jail. How can we expect them to make the proper decisions as massive and unwieldy as the trust is?”

Faulk and the others aren’t shy about expressing those feelings. The way Faulk sees it, county government has always been a place where the voices of the people have not consistently been heard. If activists’ message is gruff and hurts feelings, so be it.

“I’ve been involved in organizing for 15 years now, and one of the techniques that is used in organizing is disruption of business as usual,” Faulk said. “The reason you do that is because the rules are set up to take away the voices of citizens. What they experience is nothing compared to the inhumane treatment at the jail.”

Faulk knows a little bit about that. He was among those arrested in Oklahoma City during demonstrations in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in late May. Faulk spent about 18 hours in the jail.

“It was the worst conditions,” he said. “I can only imagine what it’s like for people there long term.”

In August, Faulk and other protesters challenged trust members to spend a night in the jail, and Everest said she “absolutely” would do so.

So far, however, that plan has only involved an initial examination of the building. News 9’s Storme Jones accompanied Everest on that tour and produced a feature story about the jail’s conditions.

Everest initially agreed via e-mail to be interviewed for this story, but that interview did not materialize.

View from the trust

Generally speaking, the displays at meetings have not been well received by the trust. Calvey regularly stares down at his phone when citizens speak during meetings. Because of meeting rules, trust members are not allowed to have an exchange with citizens who speak. It’s a one way street.

Trustee Ben Brown, a former state senator, said he agrees with much of what the protesters say, but he doesn’t like the way the meetings have unfolded.

“I have long been interested in criminal justice reform, and for me at my late age, this was an opportunity for me to help with reform,” Brown said.

During one meeting, Brown was called a “racist motherfucker” by activist Jess Eddy. Brown said he believes the protests have often slowed down the work of reform.

“It’s a slow process anyway, that has frankly been made more difficult by the people who have been crowding into the trust meetings and raising hell,” he said. “I’ve been really frustrated with them.”

Trust member Sue Ann Arnall, who runs the Arnall Family Foundation, said some of the words hurled at the meetings have been hurtful, but she added that they often still have value.

“Some of the issues that have been brought up are issues I wouldn’t have been aware of,” Arnall said. “I felt like the way they were brought up wasn’t productive, but the fact that they were brought up was productive.”

Incremental progress

Carrie Blumert is not a member of the trust, but as a county commissioner she is legally required to inspect the jail in person on an annual basis, which she did most recently in December.

Blumert said that, although there have been many bumps in the road for the trust, the jail has also seen some improvements since the body took over in July.

“I’m very encouraged and pleased with the progress they’ve made since taking over,” she said. “They have a pretty strict protocol for quarantining detainees (for COVID-19) and not mixing them with the general population.”

She said she has been particularly impressed with changes in training for detention officers.

“The whole mindset is different,” Blumert said. “They’re not encouraged to practice use of force. It’s more about self defense and de-escalation. Before, when it was run by the sheriff’s department, all of the staff went through law enforcement training, and a lot of them were deputies who had been taught use of force.”

Related:

Watch News 9 reporter Storme Jones’ story about conditions at the Oklahoma County Jail.

Blumert praised jail administrator Greg Williams, who is tasked with putting the trust’s policies into action. She said many of those improvements, such as getting rid of Styrofoam containers and changing food vendors, don’t get much attention.

“It’s not flashy things. It’s a lot of quick, short things that can make a difference,” she said. “The bigger things are going to take a while. But, while I’m encouraged, that doesn’t mean there aren’t major changes to be made.”

Brown also praised Williams and agreed that the trust has made some clear improvements.

“I think we really have made significant progress,” he said. “I think the culture is changing now, and I think Greg and his staff are implementing changes that foster more humane treatment of people. We have a long way to go, there’s no question about that. But we also have to acknowledge that some of the things that need to be done are really beyond our capacity.”

Former Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office legal counsel Danny Honeycutt sat on the trust as a member representing the department on behalf of former Sheriff P.D. Taylor. (New Sheriff Tommie Johnson assumed office Jan. 4 and was in attendance at the trust’s first meeting of 2021.)

Honeycutt said the trust’s progress has been hindered by its members.

“I wish we were further along than we were,” Honeycutt said. “I think if we were providing Greg Williams clearer instruction from one voice of the trust rather than nine individuals pulling him in different directions with different sets of expectations, I just think we’re putting him in a difficult a spot.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

The road ahead

As its raucous first meeting of 2021 proved, the Oklahoma County jail trust has a ways to go before it reaches smooth waters. But the trustees are hopeful that the year ahead can be productive.

Arnall wants to continue to explore the idea of adding a jail annex, which would allow for the medical ward and lower-risk inmates to be kept outside the main tower.

“I still would like to build that annex,” she said. “I do not want a new jail. I’m so afraid if we build one for 2,400 instead of 1,200, they will fill it. I’d also like to increase the number of detention officers so we don’t have to have people in cells for 18 to 20 hours a day. It’s cruel and inhumane to keep people confined for that length of time.”

Brown said one of the greatest challenges the trust faces is not political controversy, but rather the material condition of the jail.

“I think conditions are better,” he said. “But that’s limited somewhat to the physical condition as it is. The use of the COVID money on some repairs made to the heating and air system were good. There were parts of that jail that hadn’t seen fresh air in years. That is being repaired. The sewage system that’s broken is being repaired. But there’s still a lot more to be fixed.”

For Ekwerekwu, perhaps the most important goal ahead is re-establishing public faith in the trust’s mission.

“We have to get back to the principle of transparency,” she said. “I don’t know that we’ve ever operated within that. We have to get committed to that principle and being honest about every single thing that is going on in the jail.”