Elliott Chambers grew up in the OKC metro, attended Mid-Del Public Schools and graduated from Oklahoma State University. During his time as a student and through his early professional life, he had “never heard of” the Commissioners of the Land Office and did not know of its constitutionally defined role in providing money for Oklahoma’s public education system.

“It’s a fascinating agency. We manage assets to get as much cash into the school system as possible,” Chambers, who has been the CLO’s executive since August, said after a Thursday board meeting. “It is an unsung hero, if you ask me, as far as education funding.”

During Thursday’s meeting, state leaders approved a longterm lease for a new Kay County wind farm, purchased a pair of north Oklahoma City office buildings, celebrated a high-water mark for the agency’s School Land Trust, and approved a settlement agreement with a twice-bankrupt petroleum company.

Chaparral Energy, Inc. will have to pay the CLO $657,355.72 to resolve its oil and gas lease debts with the important but enigmatic agency, which manages state land, owns commercial buildings and makes direct payments to school districts from a sizable trust fund.

That fund has “hit an all-time high” of $2.6 billion, Chambers told the board, which has five members: Gov. Kevin Stitt, Lt. Gov. Matt Pinnell, Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister, State Auditor & Inspector Cindy Byrd and Secretary of Agriculture Blayne Arthur. (Arthur was absent from Thursday’s meeting.)

“The trust as it stands today (…) we have that invested in the market and various different things: fixed income securities, preferred securities, [real estate investment trusts], lots of different types of assets under different portfolio managers,” Chambers said after the meeting.

He said the CLO uses 13 different money managers with investments in 16 different funds.

“We spend a lot of time making sure we agree with their decisions, and if we don’t we will reallocate it from this asset class or this portfolio manager to someone else because we don’t like what they’re doing or they’re charging too much. Any income generated from those assets goes into the distribution to schools,” Chambers said. “If I remember right, off the top of my head, that was just under $100 million for [Fiscal Year 2020]. That $100 million is paid out to the school system.”

In education funding terms, money paid monthly by the CLO to local school districts is “chargeable,” meaning every dollar distributed by the CLO results in another dollar being available for the overall state aid formula.

If that sounds complicated, it is, much like every other aspect of the agency. In addition to leasing land to agricultural operations, the CLO grows its trust’s corpus with oil and gas royalties paid by companies that produce on land leased from the CLO.

Chambers said “the bulk” of the $657,000 settlement with Chaparral Energy involves interest owed by the company on “incorrect royalty payments.” The CLO filed its claim against the company in 2016.

“Long story short, they kept punting the issue, and then they went into their second bankruptcy,” he said. “It’s one of those claims that we really needed to settle it, they really needed to settle it, so we ended up at a good place.”

Kay County wind farm project developing

When it comes to commercial properties and other land leases authorized by the CLO, the agency makes payments directly to school districts and higher education institutions. On Thursday, commissioners approved a new long-term commercial wind turbine power production lease with Duke Energy on about 3,764 acres of land in Kay County.

John Fischer, the CLO’s commercial real estate director, said the 50.5-year lease marks the agency’s second time working with Duke Energy, which won an April 5 public auction to lease the land. Duke Energy Renewables Wind, LLC was the only bidder, agreeing to the minimum first-year rent price of $15,055. During the project’s development phase, annual rent starts at $4-per-acre. Once the project is producing electricity, CLO will receive 4 percent of the gross revenues with a minimum royalty of $3,500 per megawatt annually.

“Unused acreages will be released from the contract,” the meeting’s agenda said. “Agricultural use will continue on all tracts throughout the term of this wind lease.”

‘Something that is going to pay a lot more rent’

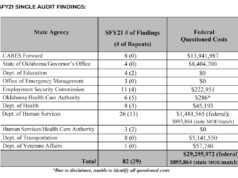

After a brief executive session Thursday, commissioners also approved CLO’s purchase of a pair of office buildings at 14201 and 14301 Calibre Drive in northwest Oklahoma City. Chambers said the buildings are about 42,000 square feet each.

“We heard that it is for sale, so we went and looked at it. We are looking to exchange a future intended sale into other properties. That other sale is for a square mile over by I-240 and Eastern (Avenue). The amount of cash we expect to get from that is just under $12.3 million. This purchase is around $10 million, and it’s a part of getting the $12.3 million and putting it into something else,” Chambers said. “[The buildings are] nearly fully occupied, which that’s what we’re going for. We want rent. So that rent, when it comes in, we pay it to the school system. So this was a way to take something that wasn’t paying as much rent and transfer it into something that is going to pay a lot more rent.”

With legislation pending, CLO still deciding custodial bank contract(s)

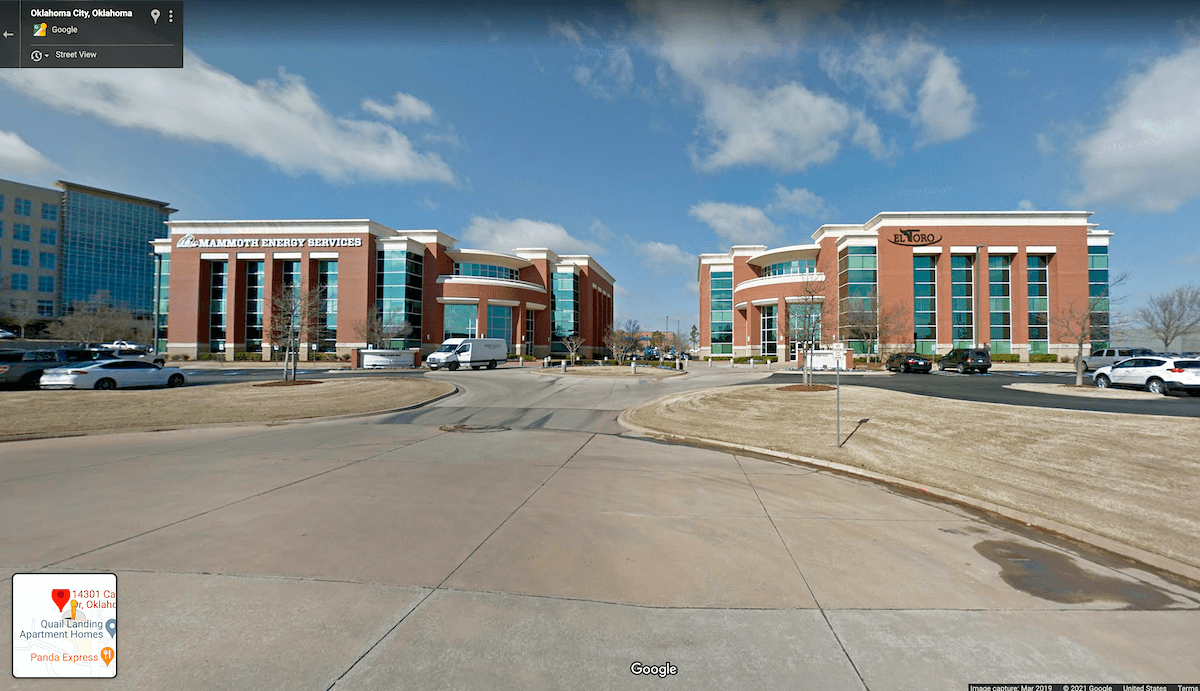

The CLO currently contracts with Bank of Oklahoma to be the “custodial bank” for its extensive financial interests, but state law currently requires the CLO to issue a new RFP every five years. That occurred earlier this year, and Chambers said Thursday his agency is still considering the applications of the four financial entities that submitted bids.

“We are fortunate. We got a lot of strong proposals,” he said. “We haven’t made a decision firmly yet, but we’re analyzing it.”

That selection process could be delayed until after the CLO sees whether its request bill, HB 2870, passes the full State Senate and is signed into law by Stitt. The bill would authorize the agency to use more than one custodial bank at a time, and it would extend the time between required RFPs from five to 10 years.

“As the trust expands, as it gets more complex, just over time (…) we have different needs — more needs than we’ve had in the past. So I want to be able to go to different custodial managers for different things. Whether it’s what we’re doing from a trust perspective for the cash coming out of the $2.6 billion or the commercial real estate portfolio, things like that. So that provides us flexibility,” Chambers said. “Going from [five years to 10 years], we get stronger interest, stronger bids, better terms from folks if they think that they have a stickier relationship with us. However, we still have the ability to say, ‘This isn’t working’ and move on.”

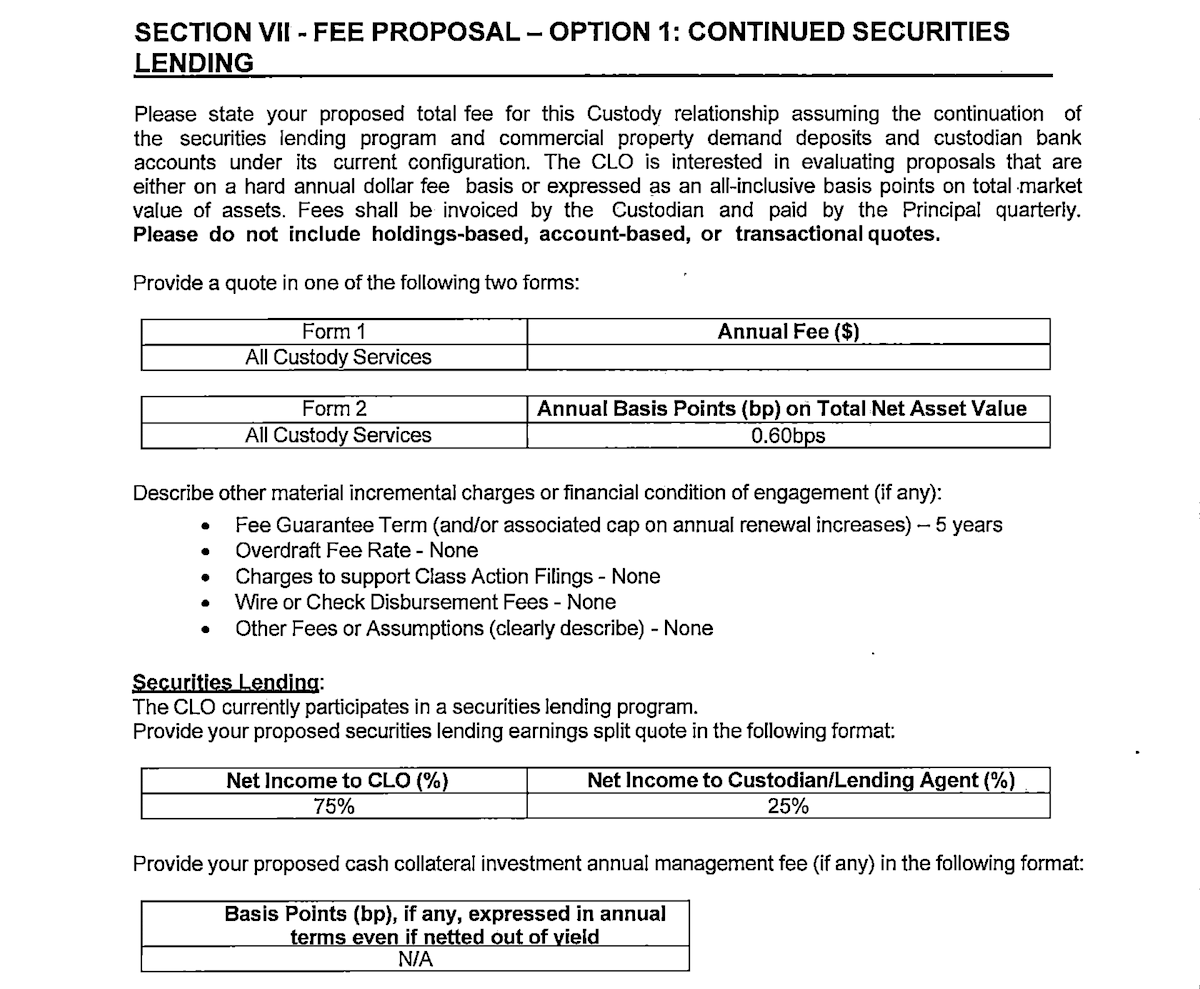

The CLO’s current custodial contract with Bank of Oklahoma is linked below, and it describes its fee structure on Page 127: The bank receives 0.6 basis points on total net asset value, which would equate to only $156,000 on a $2.6 billion trust corpus.

But the same page notes the income breakdown for the CLO’s securities lending program, which involves loaning securities to other investors or firms. Under the terms of the CLO’s 2016 contract with BOK, the bank retains 25 percent of net income and the CLO receives 75 percent.

Page 127 of the 2016 master custodian agreement between the Commissioners of the Land Office and Bank of Oklahoma lists the fee schedule. (Screenshot)

Page 127 of the 2016 master custodian agreement between the Commissioners of the Land Office and Bank of Oklahoma lists the fee schedule. (Screenshot)Current Commissioners of Land Office master custodial bank contract