(Editor’s note: If you or someone you know is in need of help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text 741-741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor right away.)

By Zachary Van Arsdale and Brenda Maytorena Lara | News21

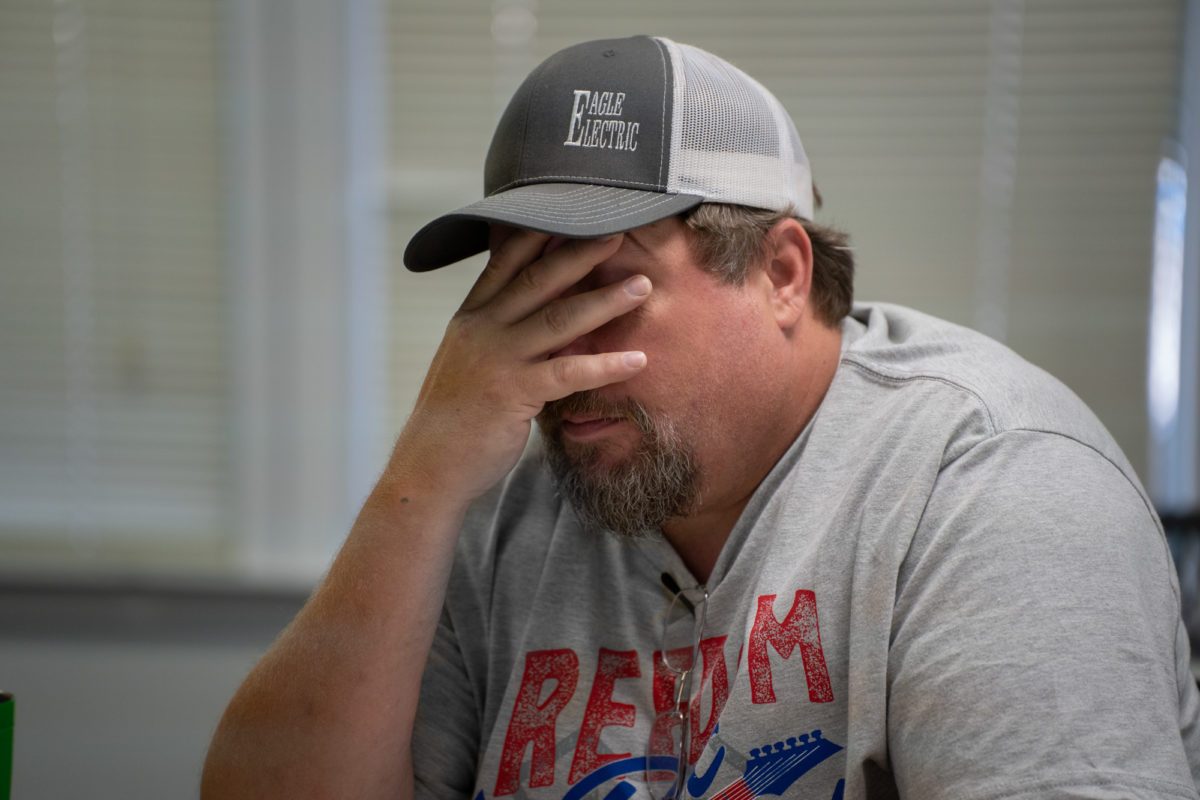

STUTTGART, Arkansas — Wayne Morgan winds his way through the clutter of chairs and hugs the other members of his Narcotics Anonymous group. He closes his eyes as they recite the Serenity Prayer.

Then he listens as others share their stories.

“I found home when I found this place,” Morgan said.

He lives a two-hour drive away in Stuttgart, Arkansas, 103 miles down the road from his addiction recovery group in Hot Springs. He visits most Sundays in his 2002 Mercury Sable that’s always on the verge of breaking down. He says it runs on prayers.

“Every day I choose to come here is a day that is saving my life, but it’s another day I’m going in the hole,” said Morgan, who is recovering from substance-use disorder.

He was 56 days sober.

“It’s another day that I’m not making a house payment. It’s another day that I’m not saving up for a car or paying off credit card debt.”

Morgan is among millions of Americans with mental illnesses such as substance use, depression and anxiety, for whom the government and community resources grew more scarce during the pandemic. Poor people, those living in rural areas and those belonging to racial and gender minorities had even worse outcomes.

“Prior to the pandemic, many people were living with mental health issues, including about 1 in 10 adults that reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder,” said Nirmita Panchal, who is a senior policy analyst at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number rose during the pandemic to 1 in 3 adults. Morgan said he could probably name 50 people he knew who died due to substance use last year.

“A lot of addicts died last year, a lot. And it’s because that one-on-one interaction wasn’t there,” he said. “And I could have very easily been one of them.”

‘Nobody’s an endless ATM’

Money was a problem before the pandemic, with patients having difficulties finding providers in their insurance networks and mental health professionals having high out-of-pocket costs. The economic strain caused by COVID-19 on individuals was especially prominent in states where Medicaid wasn’t expanded, according to the Kaiser Foundation.

In January 2021, 8.5% of Americans reported not receiving counseling or therapy even though they thought they needed it, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. The less money someone made, the less likely they were to receive therapy.

Morgan’s access to treatment for substance use disorder is mostly possible because of his family, friends and community. Medicaid provides access to medicine for his other mental illnesses, and he lives with his nephew because his own house is close to foreclosure.

His nephew sold Morgan the 2002 Sable, which used to belong to his grandmother, for $80. His local Celebrate Recovery group covered the cost of his registration tags and the first month of insurance on his car.

The bills keep coming. The pandemic halted gig work like home remodeling. Morgan spends $100 in gas each week to get to rehab in North Little Rock, plus another $40 every week to make it to his Narcotics Anonymous support group in Hot Springs.

“You reach out to your family and your friends and they help, but at some point that’s going to end because nobody’s an endless ATM,” Morgan said.

The disappearance of 12-step groups

Morgan’s 12-step meeting went from seven days a week to one day a week at the beginning of the pandemic. Now, his meeting has returned to seven days a week, but Morgan only makes it on the weekends, when he has enough gas money to travel the distance.

Many 12-step and other recovery groups in the U.S. either shut down, limited their in-person meetings or eventually went online during the pandemic, experts say. Organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous depend on donations from members.

“When there was no one coming through the doors to put the money in the basket, then those 12-step programs kind of died,” Morgan said.

In Memphis, Tennessee, the Shelby County Health Department noted a spike in drug overdoses from April 6 to May 30, 2020 — with 721 drug overdoses, 103 of them fatal, reported in the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program. In 2019, there were 58 fatal overdoses reported from April to May.

“When it first happened, it was just simply people not letting people into their (treatment) facilities,” said Mike Godfrey, the clinical director at Incura, a rehab clinic in North Little Rock. “I talked to my friend who worked at the state hospital, and he said, ‘We just quit letting people in.’”

Donation-based, member-run groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and NA couldn’t help, either, in the beginning of the pandemic.

“Not only did that make it more difficult for people already in recovery, people trying to get into recovery didn’t have a readily available meeting room they could walk into,” said Josh Weil, an overdose-prevention specialist for Shelby County.

Weil’s own AA meeting went from 50 members to five as the group met on Zoom.

“For a new person, I don’t think it’s sufficient to really get the message across what’s going on, sitting and watching people on screen talk about their experience,” Weil said. “It just wasn’t the same thing.”

The fast, slow connections of telehealth

Telehealth isn’t always an answer, even though for many it’s fast, efficient and often affordable, eliminating the need to travel long distances or take more time off work.

Telehealth also can connect specialists to people who live in medical deserts. There’s an average of one psychiatrist for every 30,000 rural Americans, most of whom receive mental health care from their primary doctors.

“To actually find a licensed therapist here, it’s tough,” said Chris Johnson, a farmer in Cheyenne County, Nebraska. He had to drive more than two hours a week to speak to a therapist before switching to phone sessions. “There’s only a handful and I’d say the mainstream medical community, from what I’ve seen, is not great at that.”

There are disparities in tech access in rural areas and for people of color. Rural areas are 11% less likely to have broadband when compared to metropolitan areas, according to the State Health Access Data Assistance Center.

Also, households with a Medicaid recipient were 9% less likely to have internet access fast enough for video telehealth visits.

In Morgan’s home state of Arkansas, Medicaid does not reimburse telehealth visits over a phone call only, requiring telehealth visits to be conducted with audio and visual communication. Rules regarding coverage of audio-only telehealth visits vary by state, with only 18 states requiring coverage.

And a computer doesn’t always connect to quality treatment.

The Mayo Clinic, in an October 2020 review, said telehealth is gaining traction for outpatient treatment, but many people with substance use disorder rely on in-person interactions.

“This has widened an already large gap between patients with substance use disorders … who need treatment and those who have actually received treatment,” the review says.

Shortcomings in racial, cultural treatment

Language and cultural barriers have impacted treatment for Latinos, other people of color and the LGBTQ+ community.

“There’s a lack of resources, a lack of bilingual, bicultural therapists,” said Noemi Legaspi, a counselor in Woodburn, Oregon, where five out of 10 people identify as Hispanic. “There are people who are bilingual, but it’s not the same, especially when it comes to counseling.”

Latino adults reported symptoms of depression 59% more frequently than non-Latino adults and reported suicidal ideation four times more than white and Black adults, according to a 2021 study published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Gay, nonbinary and transgender people lack support systems that are LGBTQ+ friendly across the U.S., especially for youths. The pandemic has highlighted a widening gap of mental health disparities between LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ individuals.

“During the pandemic, it was difficult because I was around people who I couldn’t really talk to,” said Angelica Butler, a Black trans woman in Memphis. “They shake their heads when they see me. Or (I’ve) been around folks that, every time I come around them, they side-eye me — trying (to) wonder what I am, and stuff like that. Made me feel uncomfortable, ’cause I really couldn’t just be home, like — I needed my (community).”

Butler lived and worked at Estella’s Home Care Inc., a supportive living center, when the pandemic started. She cycled in and out of the hospital because of suicidal ideation but could never get an appointment with a psychologist because of the long wait.

Eventually, Butler found My Sistah’s House, a nonprofit that provides emergency housing and resources for transgender and gender-nonconforming people of color.

“I finally found where I belong … for me, My Sistah’s House is a home. I feel welcomed. I feel loved,” Butler said.

Facetime to face-to-face time

Morgan, who attempted suicide three times before he turned around, said he finds home in the members of the recovery community through groups like NA and Celebrate Recovery.

“I lost a lot of things, connections with people. A lot of friends are gone … We’ll just never get to see their faces again, and it’s from the isolation that COVID caused,” he said.

Support groups are reopening and meeting in-person. Congress has introduced House and Senate bills to make Medicare coverage of telehealth permanent and lift geographic restrictions.

Mental health, and moves to remove its stigma, is also gaining more attention as athletes like Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles prioritize mental health over performance. Organizations such as the Confess Project train barbers to help clients open up about their mental health.

Morgan’s rehab group therapy, NA and Celebrate Recovery groups and the return to in-person support are all helping his recovery.

“When you feel like your tank might be running empty, somebody comes along and fills it up,” Morgan said.

In his NA group in Hot Springs, the hour is almost up. Tags to mark milestones in their recovery are handed out.

The members stand, form a circle shoulder to shoulder and wrap their arms behind one another’s backs. Each extends one foot into the circle to symbolize those who are still suffering.

Once again, they recite the Serenity Prayer.