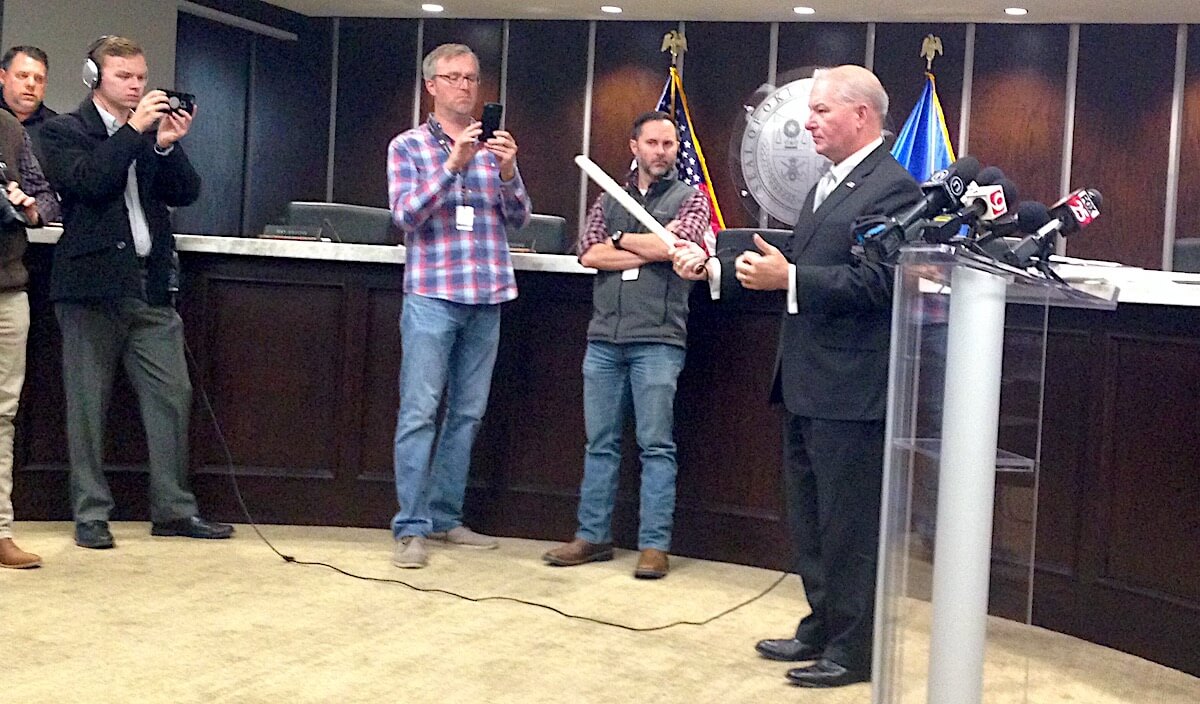

The Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office initiated its first body-worn camera program last week, with 40 new Axon Body 3 cameras designated for deputies in “divisions tasked with traditional law enforcement duties that involve a high frequency of enforcement contact with the public,” according to the OCSO’s policy statement.

As explained in the video above, issues regarding data storage have complicated law enforcement agencies’ body-worn camera programs for years, which is why Oklahoma County Sheriff Tommie Johnson III says his team selected a cloud-based storage vendor.

“When you talk about body cameras, the biggest expense is storage,” Johnson said. “The ability to store all of this information and this data, it’s a very large profile that it takes up. But the cloud allows us to expand as we need.”

Other common delays for the implementation of body cameras can include disagreement over operational policies and procedures. But after making body cameras a key priority during his successful 2020 campaign for sheriff, Johnson and his team have developed and launched a body camera program in less than one year.

“I’m just beyond proud that, within eight months, we made good on that promise,” Johnson said. “As part of running a campaign, you make these promises that these are the changes we will make. When we came in, a part of our command staff, a part of our vision, a part of those goals was to make sure that we got these body cam systems in for our guys to use, because our community deserves it and the agency deserves it.

When (and when not) to turn body cameras on

Embedded below, the new body-worn camera policy statement for the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office is nine pages long. It outlines the purpose of the program, procedures for use and the length of time various types of recordings will be maintained.

It also outlines when deputies can review footage during an investigation and establishes a protocol for requesting that portions of or entire recordings be redacted or deleted.

“Body-worn cameras provide objective recordings of events deputies encounter,” the policy states. “These recordings provide valuable evidence for prosecution, assist deputies with completing reports, protect deputies from false allegations, and hold deputies accountable for their actions.”

Earlier this month, deputies received training on how the cameras are configured and how they can be programmed to turn on automatically when a weapon is drawn, when an OCSO vehicle’s emergency lights are triggered and even when another person comes within a certain distance of a deputy.

The OCSO’s body-worn camera policy statement lists instances when the cameras shall be activated:

- Voluntary contact / consensual encounter;

- Prior to any investigative detention, mental health detention, traffic or vehicle stop, motorist assist or custodial arrest;

- Prior to a use of force;

- Prior to initiating any Code 3 (lights and sirens) or emergency response;

- Prior to exiting the OCSO vehicle on a call for service;

- While involved in any vehicle or foot pursuit;

- When conducting a standardized field sobriety test or drug recognition expert (DRE) evaluation, or while reading the Oklahoma implied consent warning;

- While transporting, guarding or coming into contact with any person who becomes uncooperative, agitated, combative, threatening or makes statements related to his or her arrest / protective custody;

- For the purpose of documenting a dying declaration;

- When directed by a supervisor.

The policy notes that deputies also may choose to activate their cameras “anytime the deputy deems it appropriate to record for official purposes, except as prohibited by this policy.”

The policy specifies times at which cameras shall not be activated or shall be deactivated:

- During a conversation with any supervisor or investigator after an incident has been resolved;

- During activities, conversations or meetings with law enforcement employees while not on call or incident;

- During planning or briefing with the tactical unit or bomb squad at any time;

- At the conclusion of a call or incident;

- While maintaining a secured crime scene after an incident has been resolved, if approved by a supervisor.

The policy provides rules for activating body-worn cameras in health care facilities and for uploading recordings to the OCSO cloud system, which “shall be completed no later than the end of the deputy’s shift.”

“If a deputy does not make a complete recording as required or interrupts a recording, the deputy will document the circumstances of such action in the appropriate report,” the policy states. “The use of a body-worn camera does not alleviate the responsibility for a deputy to complete a detailed report related to their involvement in an incident as required by written directives.”

When should footage be reviewed?

One component of the OCSO’s new policy mirrors an Oklahoma City Police Department protocol that an independent consultant recently recommended changing. That OKCPD policy currently allows officers to review body cam footage of critical events prior to making their official statements.

Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater calls that policy “problematic” for any agency, and he said he was glad to see OKCPD Chief Wade Gourley voice support for the recommended change.

“This is one of the most frustrating things about body cameras that affects a lot of the investigations of police officers that we look at,” Prater said. “The problem with [prior review of footage] is you may have an officer who is completely legitimate in their use of deadly force. You want that officer to make a statement based on what they believed at the time, what their perception was and why they used deadly force.”

Under its new body-worn camera policy, OCSO deputies “will be allowed to review his or her body-worn camera recordings or the portion of another deputy’s recording” for purposes of assisting with investigations, prior to testifying in court and “before making any statement or being interviewed.”

“If the deputy is the subject of an administrative investigation, he or she may have an employee representative/legal counsel present during the review,” the OCSO policy states. “If the deputy is the subject of a criminal investigation, he or she may have legal counsel present. If requested by the deputy, employee representative or legal counsel, the review of the recording shall be conducted privately so that the event may be discussed.”

Like Johnson, Prater formerly served as an officer in the Norman Police Department. Now Oklahoma County’s district attorney, Prater said he believes law enforcement officers should make their initial statements about critical events prior to reviewing their body-camera footage.

“What you get is you have an officer who goes into a room to view their body camera video before they make a statement to homicide detectives, and their memory does not match with what they’ve seen on the camera,” Prater said.

That can cause law enforcement officers “to morph their statement and try to make it conform with what they saw, even though they remembered it differently,” according to Prater.

“That makes it look like it’s a dishonest statement, even though they may not have intended in any way to be dishonest,” Prater said. “That’s just human nature: ‘I know what I remember about the event and things were happening really quickly, but when I saw my body camera that’s not what I did, and in my statement I need to have my statement more conform with what I saw.'”

Prater said the human brain can react differently during “critical incidents” and does not always collect data in a linear manner.

RELATED

‘A long time coming’: More Oklahoma communities implementing police body cameras by Heide Brandes

“You’re in a flight-or-fight mode, you have the cortisol and the adrenaline and everything going through their body, and parts of your brain actually shut down. Some of those affect your memory,” he said. “So we know that officers are not going to remember everything. Yet when they go in and they watch their video before they even give a statement, it completely alters what they are willing to say about what they remember, and so it hurts them.”

Prater said that, as a prosecutor, he understands if an officer’s statement “doesn’t exactly make sense” after a critical event because “we can all understand the stress of that moment.”

“But what is difficult to explain is when they go in and they start to talk about things that it doesn’t seem like they are being honest about what they are remembering, because they have just seen their video,” Prater said. “So that is really problematic.”

Prater said departmental policies should instruct officers to make their initial statements, then review the body-camera footage and ultimately make a clarification if necessary.

Since the OCSO’s body-worn camera program is brand new, only time will tell whether policy adjustments will be made.

“This is a practice that is commonly used by police departments throughout the country, and we will make changes to it as we see fit,” said Aaron Brilbeck, the OCSO’s public information officer.

For now, Johnson said his agency is simply excited to deploy the technology and “document exactly what happened” during incidents.

“This gives clarity to situations where many people may be unsure of what happened,” Johnson said. “This is that added level of protection, and the deputies understand that now.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office body cam policy