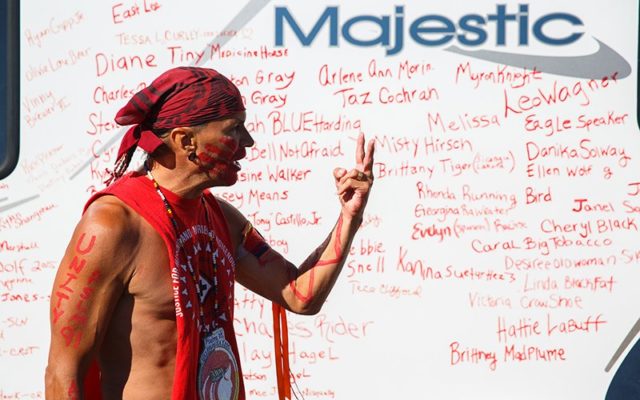

WASHINGTON — Duane Garvais-Lawrence pulled into Washington, D.C., on Friday, ending his second annual coast-to-coast trip to bring attention to the problem of missing and murdered Indigenous women — a trip he hopes he does not have to make again.

“The blood on this RV (…) is on America’s conscience,” Garvais-Lawrence said of the red names of victims written on the side of the vehicle. “Enough is enough.”

Garvais-Lawrence left Washington state on July 18 and has spent the months since driving from reservation to reservation as part of his MMIW Bike Run USA. At each stop along the way, he and others who joined him on the trek would bike, run and pray to raise awareness of the issue. At each stop, they would add names of victims to the side of the motor home in red ink.

This story was reported by Cronkite News, a news division with Arizona PBS. CN is partnered Gaylord News, a Washington reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Oklahoma.

Even as Garvais-Lawrence starting on Sunday to make his way back to Washington state in his RV, people were seeking to add names of victims, including two from Oklahoma: Cherokee citizen Audrey Dameron (missing since 2019) and Cheyenne and Arapaho citizen Ida Beard (missing since 2015).

“There are probably few American Indians that haven’t been touched by MMIW,” said Patricia Hibbeler, chief executive officer for the Phoenix Indian Center and a member of Arizona’s Study Committee on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

“If it’s not somebody in our family, we know of someone — or relative of someone — that sadly has been murdered or missing,” she said.

‘There are a lot of problems with the data’

The committee Hibbeler served on was created by lawmakers in 2019 to “conduct a comprehensive study to determine how this state can reduce and end violence against indigenous women and girls.” It painted a grim picture of the situation.

More than 80 percent of Native American women, or more than 1.5 million people, have experienced violence in their lifetimes and 56 percent have suffered sexual violence, the report said. One in three had experienced violence in the past three years.

Indigenous women were 1.2 times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to experience violence in their lifetimes and 1.7 times more likely to have experienced it in the previous year.

But the first problem for advocates is that no one fully understands the size of the problem.

“There are a lot of problems with the data,” said Hibbeler, adding that missing indigenous people are underrepresented and underreported by law enforcement and government agencies across the country.

Arizona Rep. Jennifer Jermaine (D-Chandler) said part of the problem is that police do not always identify victims as Native American. Or they are reluctant to ask.

“We don’t have an exact number because there’s racial misclassification in the databases (kept by law enforcement),” said Jermaine, who chaired the study committee.

The report also found that more than half of family members and survivors did not think law enforcement agencies across the board — federal, state, local or tribal — were helpful in their cases. Hibbeler said racism plays a large role in how aggressively police respond to MMIW cases.

Police response is a concern for Raymond Cavanaugh, a citizen of the Spirit Lake Nation in South Dakota, who joined Garvais-Lawrence a couple of weeks ago, biking and running in several Indian reservations before arriving in D.C.

“Officers are shorthanded on the reservation,” Cavanaugh said Friday. “There’s usually only one officer responsible for the safety of thousands of people.”

Cavanaugh, Garvais-Lawrence and others met Friday with Bryan Newland, the assistant secretary for Indian affairs at the U.S. Department of the Interior, to discuss ideas to support the MMIW movement. Those ideas ranged from law enforcement accreditation and increased resources for tribal police to policy changes that would not count losses in MMIW cases against an attorney’s prosecutorial record.

Jeff Stiffarm, a tribal council member from the Fort Belknap Indian Community in Montana, said another possible solution would be to lift the 48-hour waiting period before a person can be reported missing.

“Law enforcement waits 48 hours before they consider someone missing,” Stiffarm said. “But a lot can happen in those 48 hours, and that’s why they’re never caught.”

Jermaine said that change came to Arizona this week, with a new law that does away with the 48-hour waiting period when it comes to missing children of any race, gender or ethnicity.

Under the legislation, police stations that receive a missing child report are required to file it to state and national databases within two hours and follow it within 30 days with more detailed information, including recent photos and dental records, when possible. Authorities are not allowed to remove the information from any database until the child is found or the case is closed.

“This is a significant shift in how these cases have been approached in the past,” Jermaine said. “The waiting period can play into cases going cold.”

She said there have been other recent breakthroughs. On Thursday, Jermaine said, police in Fort Worth, Texas, arrested a suspect in the disappearance of Tanya Begay, who was last seen on the Navajo Nation in 2017. For years, law enforcement had no leads in her disappearance.

Hibbeler said there are other hopeful signs, if for no other reason than people are now paying attention to the issue. In addition to the study group, she said, the Phoenix Indian Center offers awareness sessions throughout the year and classes on making red-ribbon dresses in remembrance of missing women.

Garvais-Lawrence created a GoFundMe account to raise funds to help families and groups that he met along the way. He said he supports other awareness efforts because the issue is so important.

Too important, Cavanaugh said, to stop pushing on the issue.

“You wouldn’t want your body wrapped and dumped somewhere,” he said. “These families want justice and we must get it.”