Lewis Stiles Gannett (1891-1966) was a columnist for the New York Herald Tribune who took his wife and teenage son on an automobile trip across the country in the summer of 1933.

The family car had no radio or any of the dashboard distractions so common nowadays. The Gannetts had a copy of Carl Sandburg’s American Songbag, and they tried a bit of harmony, but nobody could read music, and their efforts at vocalizing failed miserably.

Some sort of diversion was essential, however, because, as Gannett observed, “There is a lot of country to cross in the United States, and not all of it is exciting.” Suggesting, of course, that before it was “flyover country,” Oklahoma “driveover country.”

The Gannetts solved their entertainment problem by picking up hitchhikers, despite several warnings they had received from acquaintances: If hitchhikers don’t hit you in the head and steal your stuff, they will sue you for some injury they sustained from riding in your back seat.

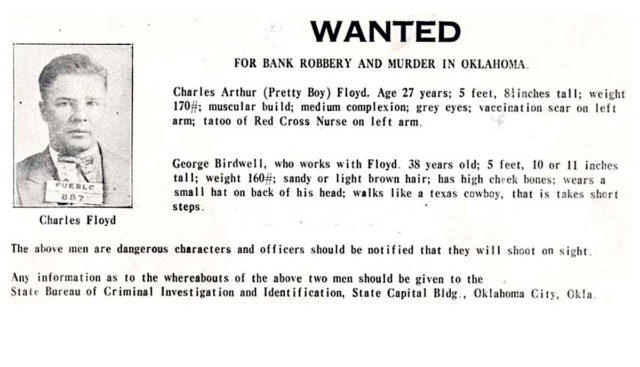

Nothing criminal occurred, but there was plenty of talk about criminality. As the Gannetts neared Oklahoma, the hitchhikers told them all about Pretty Boy Floyd.

The mysterious reputation of Pretty Boy Floyd

Born Charles Arthur Floyd in rural northern Georgia in 1904, he was Charley to family and “Choc” to friends with whom he drank enough Choctaw beer to warrant the cognomen. The Floyd family moved to Akins, Oklahoma, in Sequoyah County, and Charley worked in cotton fields.

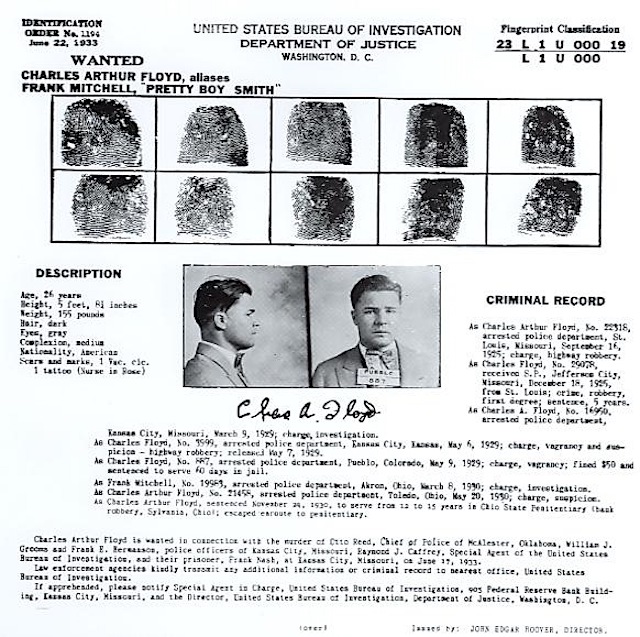

After hitting the road as a hired hand for wheat harvests at age 16, he was introduced to bootlegging and other criminal enterprises, serving four years in the Missouri State Penitentiary for a payroll robbery and embarking on other heists after his release. Various stories exist about how he came to be known as “Pretty Boy,” but there is no doubt that he hated the name and would not answer to it.

The hitchhikers encountered by the Gannetts called him “Pretty Boy” and knew all about Floyd, a noted bank-robbing outlaw with a mixed reputation among the public. Some people said Floyd was a Robin Hood-esque figure who would not purloin the deposits of a struggling farmer. Others said he was selfish and paid no mind to whose money he stole.

Law enforcement officials could not lay hands on Floyd, but the hitchhikers the Gannetts encountered knew exactly where he was — or so they said — but no two seemed to agree. He is in a cave over there. No, he has a hideout over here. Etc., etc., etc., said the King of Siam.

With more than two dozen bank robberies attributed to him (with varying credibility), Floyd achieved notoriety in national media during the Great Depression and became a folk hero for the poor and disillusioned, although his 1932 shooting of the popular lawman-turned-bounty hunter Erv Kelley dampened the enthusiasm of some Floyd fans.

The New York Times referred to Floyd as a “southwestern desperado,” a “long-hunted outlaw,” the “notorious Oklahoma outlaw” and the “Oklahoma machine gunner,” among other titles. Arkansawyers and Texans took exception to Floyd’s identification with Oklahoma. He was from Arkansas, some from that state claimed. Some Texans said he was from west Texas. Others south of the Red River said he was no Texan but a Chicago gangster, maybe even a foreigner, going by an alias and living on the real Pretty Boy’s notoriety.

Gannett wondered if all this contradiction might lead to the same sort of “history” that was emerging about Jesse James and Billy The Kid. Did anybody really know anything when it came to outlaws and their supposed deeds?

During the trip, Gannett wrote columns about the West and sent them back to the Herald Tribune. And, in 1934, he published them in a book entitled Sweet Land, illustrated by his wife, Ruth. The book is of interest for several reasons.

The summer of 1933 was the occasion of the so-called Kansas City massacre, wherein a number of law enforcement officers and FBI agents were killed, along with the prisoner they were transporting. Pretty Boy Floyd was named as one of the shooters, although questions about his involvement linger to this day. By 1934, the details of Floyd’s purported involvement — as reported by lawmen and newspapers — were known far and wide. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had made Floyd a public enemy and the object of Hoover’s personal crusade. But none of that made it into Sweet Land.

Hitchhikers had assured the Gannetts that they had nothing to fear from Floyd, should they meet him. Floyd only shot sheriffs, they said. Never tourists. That Kansas City business would have muddied the waters, Gannett may have concluded. And what a yarn. Floyd only shot sheriffs in the head, supposedly. The list of victims was a long one, some said, and Gannett’s informants told him Floyd had only ever missed once.

That is not history. It is folklore. And in 1944, that particular Gannett hitchhiker story appeared in B.A. Botkin’s A Treasury of American Folklore. Botkin had ties to Oklahoma and may have selected the most outrageous and unbelievable of the Floyd stories for the sake of the state’s reputation. But Gannett had indicated that while Oklahoma was “driveover country,” it was also “don’t stop country.” Describing accommodations and cuisine experienced by the family, Gannett wrote, “Only once did we meet really bad cooking — in Chouteau, Okla. — and we took our chances ….”

As should we all in diners near where sheriff-shooting bank robbers dwell.

An uncertain end for Pretty Boy Floyd

Floyd died 87 years ago today in 1934, shot and killed while on the run from the FBI and local law enforcement in East Liverpool, Ohio. The exact circumstances of his death are almost as muddy as the picture of his life.

Following the Kansas City massacre in June 1933, Floyd was believed to have fled to New York state for more than a year. Newspaper columnists reported rumors that he had undergone a face lift to disguise his identity, perhaps a planted story to relieve pressure on law enforcement who could not seem to find him.

In October 1934, Floyd and an alleged accomplice in the Kansas City massacre were spotted in eastern Ohio, possibly while embarking on a return visit to Oklahoma. On a farm in East Liverpool, Floyd died at age 30. The official online FBI account of Floyd’s death omits details about who shot Floyd, claiming he had been hit twice and died 15 minutes later as agents waited for an ambulance. G-Man Melvin Purvis and his team were celebrated for stopping Floyd and his accomplices.

But in September 1979, an 84-year-old retired East Liverpool policeman named Chester Smith said in Time Magazine that he was one of six officers accompanying Purvis that day and that he had spotted Floyd attempting to escape through a cornfield. Smith said he dropped Floyd with two shots from his rifle and then disarmed him. Smith said Purvis ran up and demanded to talk to Floyd, who cursed at him. Smith said Purvis instructed another FBI G-Man to “fire into him” with a Tommy gun.

Subsequent public discussion ensued in 1979, with the FBI calling Smith’s claim a lie. More folklore, perhaps? A final, postmortem question mark to hang over the Akins gravestone of a man whose large legend always overshadowed any ability to find the truth?

The question, of course, is what does an 84-year-old man gain from telling a lie?