I greatly enjoy many wonderful features of Central Park and other near-midtown Oklahoma City neighborhoods, and CommonWealth Urban Farms in my local community is my favorite. Its co-founders, Elia Woods and Allen Parleir, created numerous community gardens while working with at-risk youth, and now they are improving the community with native grasses, pollinators, vegetables and cover crops. Allen and Lia have decades of experience in environmental education; and they share a library of science-based books, such as 2020’s Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation that Starts in Your Yard, by Douglas Tallamy.

During my decades of community gardening in Central Park, I tried, unsuccessfully, to keep up with emerging environmental science. At best, I would learn from the experience and research of CommonWealth gardeners. It wasn’t until Allen and Lia loaned me Tallamy’s book that I realized what I had not understood about ecosystems. Belatedly, a light went on, and I started to grasp the science which explains the transformative, collective role that community gardens can and must perform. According to Tallamy, the “stewardship” that gardens embody may be “nature’s and thus humanity’s best hope.”

Creating ‘island biogeography’ in your neighborhood

In the book, Tallamy first builds on the legacies of Aldo Leopold and E.O. Wilson. Leopold “dreamt of a time when people humbly accepted their roles as citizens of the natural world rather than its conquerors.” Then, foreshadowing 21st century environmental science conclusions, he explained how wilderness is “a truly awesome and unimaginably complex machine that required all of its parts to function well.”

RELATED

Master gardener: Quit wasting money in your garden by Fred Schneider

Wilson explained the “infinite diversity of species that reside on Earth today, as well as the many imminent threats to their future.” He concluded that a “sixth great extinction” would devastate our world if we could not devise holistic approaches to sustaining the “living portions of our planet.” Wilson’s most achievable proposed solution was to “save half of the earth” by creating “island biogeography” where biodiversity could recover in corridors where plants, insects and wildlife could interact with each other. Since 83 percent of the United States’ land is privately owned, that goal was often seen as impossible.

Tallamy agrees that worthy efforts, such as protecting endangered species, preserving wilderness, and other conservation goals, are not enough to save our planet. However, he argues that one of humanity’s great destroyers of nature — our 164 millions of acres of urban and rural residences — could be a key to creating “biological corridors” which can become a home for the biodiversity that has been disappearing so rapidly. He dubbed these diverse spaces as the “Homegrown National Park.”

Tallamy explains that if each American landowner would turn “half of his or her lawn to productive native plant communities” then “millions of acres now covered with lawn can be quickly restored to viable habitat by untrained citizens with minimal expense and without any costly changes to infrastructure.”

One first step toward sustainable, biodiverse corridors is coming to grips with the costs of the pervasive monocultures of lawns, as well as the lost opportunities due to planting nonnative plants. But that requires educating people like me, who understood there are problems with invasive plants, but who were unaware of the new science on the downsides of planting beautiful Asian imports that don’t fit into our biodiverse environments. For instance, a decorative Japanese plant is likely to produce attractive berries during the seasons when Asian native insects and birds feed on them, but not when our birds need them before starting their annual migrations. Such exotic plants are “host-plant specialists” that have evolved to fit into the biosystems they come from but that don’t enhance food webs in Oklahoma yards.

Tallamy explains this “curse of specialization” where:

Animals benefit from the energy captured by photosynthesis only if they eat the plants, or eat something that ate the plants previously. And there is the rub: insects are the animals that are best at transferring energy from plants and other animals, and, unfortunately, most insects are very fussy about which plants they eat.

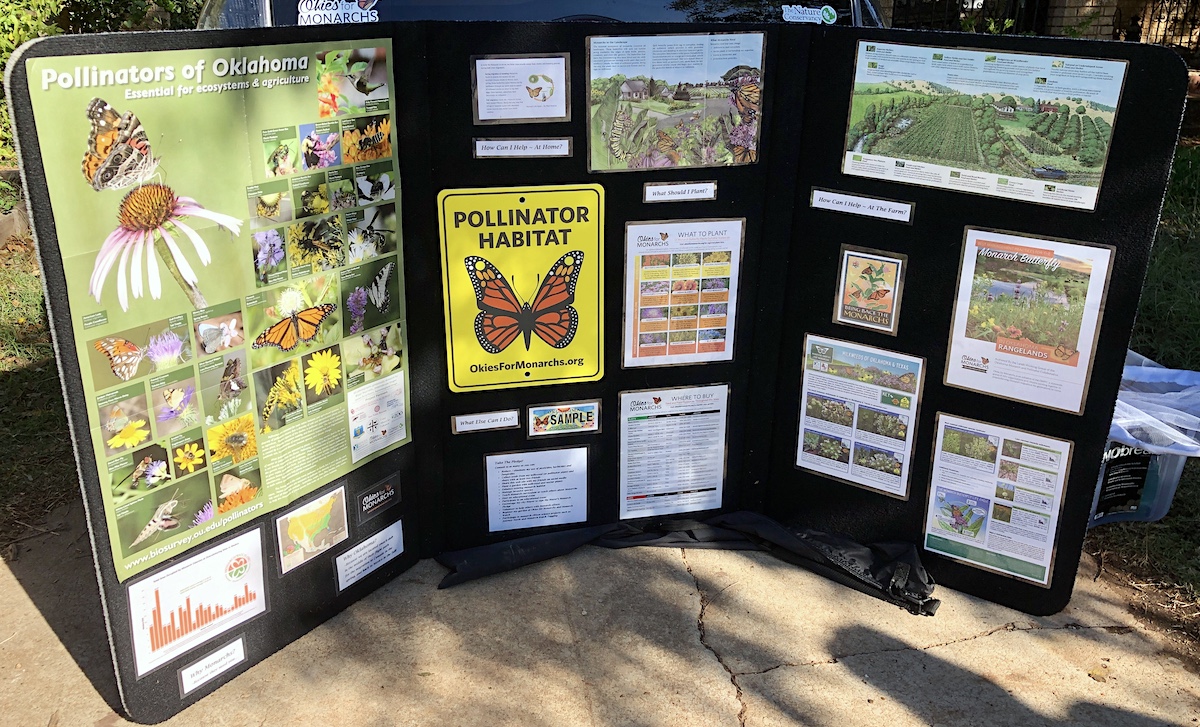

So, Tallamy seeks environmental education that explains the role of extremely productive “keystone” species, such as domestic pollinators, milkweed and oak trees. Bringing young people into the conversations is crucial to raising consciousness, and hands-on lessons, such as building caterpillar pupation sites, are great ways to capture students’ attention. In fact, when Tallamy spoke in Oklahoma City in June 2020, he stressed the importance of protecting and nurturing caterpillars. (He is scheduled to return in February 2022 to speak at the Oklahoma Native Plant Society.)

An unprecedented number of bees

Hopefully, a younger generation of gardeners will help us with these tough and necessary conversations, such as the need to shrink our lawns, remove invasive species, and stop the spraying of pesticides and fertilizers. After all, they are growing up in a time of unprecedented wildfires, floods, hurricanes and the melting of the Arctic ice. In October 2020, Oklahomans experienced an unprecedented ice storm that overwhelmed the electric grid. This year, we faced extreme winter storms, thunderstorms and tornadoes. The urgency of the moment is not lost on our kids.

This spring, as I started to wrestle with the questions raised by the invasive species that took advantage of previous community gardens, my wife, Jocelyn, only planted the native species she purchased from CommonWealth Urban Farms. The results were amazing. These plants attracted an unprecedented number of bees, Monarch butterflies and other pollinators.

Tallamy describes New York City’s High Line gardens as the type of success story that should be emulated. CommonWealth Urban Farms is an example of how Oklahoma City neighborhoods could become recognized for collective action to nurture corridors of biodiversity. If New York City can become the “greenest big city on earth,” then Oklahoma City can learn from it, Tallamy’s book, and Commonwealth Urban Farms. If we do, we will become a comparably biodiverse city where young people are intimately connected to nature.