In September, Silo Public Schools Superintendent Kate McDonald had hopes that voters would approve a $33.5 million bond issue for constructing a new “state-of-the-art” high school to replace the district’s current 1970s building, which she says the school has completely outgrown. Teachers, students and their parents were tired of splitting rooms in half and using storage areas for classroom space.

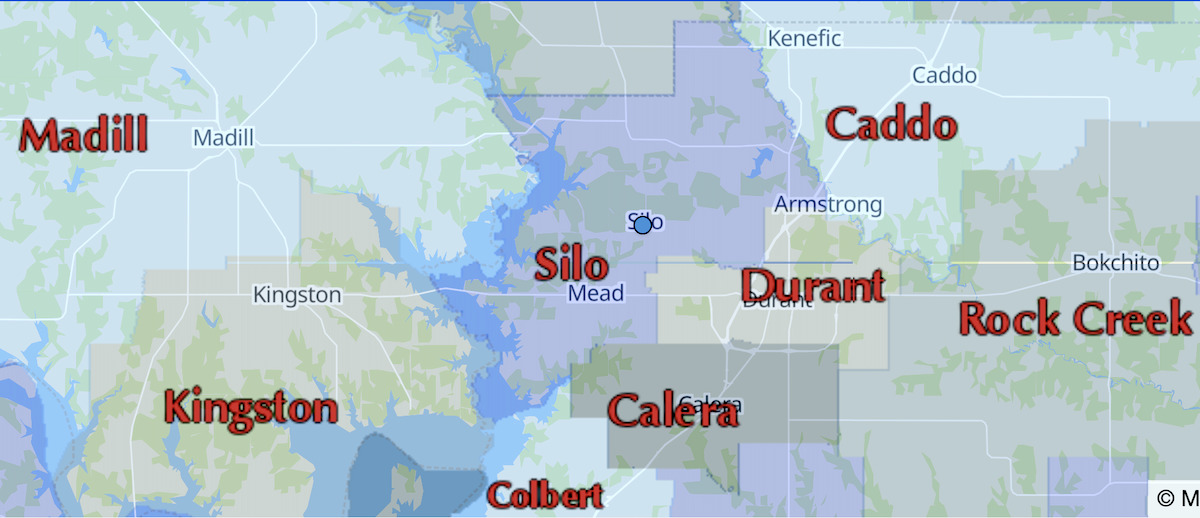

Located outside of Durant, the district had its first bond issue in two decades approved by voters in 2017, with $11 million going toward a new elementary school. However, the September bond issue failed after only 31.5 percent of ballots were cast in approval.

“We’re paying for the issues of not passing one for 20 years,” McDonald said. “We’ve done great things, and we have awesome teachers. The facility isn’t everything in education. It’s what you put into that facility and the people you put in there. But, still, our kids deserve to have that. There shouldn’t be any difference when you drive five miles to another school. Our kids are great kids, and they deserve that, too.”

School districts in the state present bond issues on election ballots for voter approval. Issuing bonds, which are bought by private investors, can provide districts up-front funding for school site improvements, technology purchases and transportation upgrades. Districts pay off their bonds over time with local property tax revenues. State law requires that bond issues receive at least 60 percent of the vote in order to be approved.

A total of 99 Oklahoma school districts placed bond propositions on election ballots in 2021, and 79 districts have had at least one of their presented propositions approved by voters. But getting a bond issue approved by voters can be a complicated endeavor that depends on extensive planning, the right messaging and voter turnout. When school bonds fail, the effects of rejection can linger.

“You can look at communities that haven’t passed bond issues, and there’s a consequence to it,” Elgin Public Schools Superintendent Nate Meraz said. “Their buildings are old and not up to date. Morale is a key issue. If you’re showing up to a building that looks like it’s being bandaged up all the time, it can impact morale and the whole feel of the community.”

Meraz also said that once school bonds fail in a district, it can be hard to catch back up.

“I took over from a very savvy superintendent. We’ve kept this thing going,” Meraz said. “We don’t ever want to get to the point where people relax and think that we can just sit on our heels.”

‘We can’t outrun the growth that we’re seeing’

A total of 1,280 ballots were cast in the September bond issue election for Silo Public Schools. According to the Bryan County Election Board, 5,048 registered voters reside in the Silo district. McDonald said she believes the bond proposal was hurt by inaccurate social media messaging from opponents.

“We’ve had a lot of people who have no ties to our community that wanted to speak out against the bond who don’t bring their kids to our school,” McDonald said. “That was a big hit to us.”

McDonald said some people simply weren’t willing to pay the more than 20 percent property tax increase the bond proposal would have caused.

“I did have a lot of the older people in our community, who we treasure and we want to take care of, as a coalition call us after the election and say, ‘We know that you need that, we just don’t want to pay for it,'” McDonald said. “That’s hard for us. How do you overcome that when it’s the only way in Oklahoma we have to do such a project? We’ll never save the money in our building fund to build a building like that. We just won’t generate those kinds of funds through our county. We don’t have a city sales tax, we don’t have a town — we’re just a district outside of Durant.”

McDonald said the district had a 2012 enrollment of about 780 students, but current enrollment sits at about 1,100 students. As more job opportunities and housing become available within the area, McDonald expects the growth to continue.

“We needed everything in that bond issue. We needed a cafeteria, we needed a gymnasium and, of course, we needed those classrooms,” McDonald said. “Right now, our 7th through 12th grades are in the same building, and we’re packed to the brim. We have classrooms that we split in half to make two classrooms out of one.”

McDonald said the district will look into proposing the projects again in separate packages for future elections, which could end up costing taxpayers more as building costs increase.

“With it not passing, that’s a huge hit to our school. We needed it now, not later on down the road. We needed it right now,” McDonald said. “Now we’re looking at having to break the bond up and run it in pieces. We can’t outrun the growth that we’re seeing.”

In 2016, a comprehensive school bond issue totaling about $45.5 million for Elgin Public Schools narrowly failed by receiving only 53.35 percent of the vote. The funds were slated for the construction of a STEM classroom, a new agricultural technology building, a performing arts center, air conditioning for the high school gym and other athletic improvements. The bond proposal was projected to raise local property taxes about 11.8 percent.

“The bottom line is, it’s money — people’s tax dollars,” Meraz said. “I think, psychologically, there’s certain percentages that are just too much.”

Meraz said administrators had put a lot of work into preparing the initial bond proposal, holding informational meetings and sending surveys to give community members an opportunity for feedback.

“You do all that and then it fails, but it doesn’t fail miserably, so that lets you know that there are some things (in the bond issue) that you can probably hone in on,” Meraz said.

‘Band-Aid on a pig’: Prank affects Atoka bond proposal

Situated in southeast Oklahoma, Atoka Public Schools watched a $13 million bond proposition fail in September. With only 488 ballots cast, the proposal received about 42.39 percent of the vote. According to data from the Atoka County Election Board, 2,296 individuals are registered to vote in Atoka Public Schools elections.

Atoka Superintendent Jay McAdams partially attributed the failure of the measure to some community members being upset by the district’s reaction to a senior prank last year.

“We had about a third of our high school graduating senior class, right before graduation, break into the school,” McAdams said. “They didn’t really tear up anything, but they broke into the school and did a lot of things. They called it a senior prank, but once they broke into the school, they kind of made it a situation. So, I had about 33 kids that we didn’t let walk across the stage. I think part of it was the backlash on that. A lot of the parents and some of the people felt like maybe that was too harsh of a punishment. I think there was some carryover on that.”

McAdams also noted that he felt he could have done a better job with messaging surrounding the bond issue.

The proposed bond funding for Atoka Public Schools would have gone toward a multi-purpose center with an esports arena, STEM labs and a new career tech facility for plumbing and HVAC technicians. It would have also funded the installation of accessible seating at the football stadium and the district’s aging gymnasium. McAdams said the bond was not projected to increase taxes owing to prior bonds being paid off. McAdams said it marked the first time he could recall seeing a bond issue fail when it did not feature a property tax increase.

“We’re kind of the leaders in southeast Oklahoma on esports,” McAdams said. “One of the things we’ve done with our esports courses is that we require our kids to go through the coding and some other classes, like robotics, in order to be part of the esports, which goes along with our STEM and our aviation.”

McAdams said the multi-purpose center was planned to have a STEM lab on one end, an esports arena, a basketball gym, practice space for cheerleading and a Career Technology Center.

“We were really trying to tie everything together with this facility,” McAdams said. “Our current gym we have is 40-something years old. I ended up having to spend about $30,000 worth of repairs on that, just to make it where we can still continue to use it. We probably have to spend another $100,000 on that facility for a new roof.”

McAdams said the funds needed to repair the gym ended up coming out of the district’s building fund, which receives a total of about $125,000 a year and doesn’t go particularly far at a district with a student population of a little less than 1,000.

“Now I need to find a way to generate and do a lease purchase on replacing the roof on it, but we’ll do what needs to be done,” McAdams said. “Eventually, they’re going to have to run something. Because all we’ve done over in the old facility is basically put a Band-Aid on a pig. We’re going to do the best we can to keep our facilities up and clean and functional. But we have some issues over there that are going to be a constant expense.”

McAdams said presenting the bond issue again at a future election was a topic of conversation at a board meeting after the bond’s failure, but he doesn’t know exactly when the district will try again.

“You have to wait six months before you can run it again. I just think right now some things need to settle down and we need to start putting our game plan together,” McAdams said. “Before we run it again, we need to make sure we have all our ducks in a row in exactly how we’re going to attack it.”

This year, Sallisaw Public Schools attempted to re-present a $3.5 million bond issue on the October election ballot that had failed months prior. In March, the proposal received only 51.85 percent of the vote, with 1,190 ballots cast.

The bond proposal would have raised property taxes by about 6.93 percent and would have allowed the district to match a $3.5 million Federal Emergency Management Agency grant to build four storm shelters on the district’s campuses. However, the ballot measure saw even less voter support during the October election, with only 48 percent of ballots cast in favor of the bond issue and 1,398 ballots being cast.

Sallisaw Schools Superintendent Randy Wood told the Sequoyah County Times in October that if the bond issue failed a second time, it would “go away.”

For Elgin Public Schools, the 2016 bond’s failure prompted school administrators to head back to the drawing board and back into the community to figure out how to get the proposition approved by voters in the near future. Those discussions led the district to remove some athletic items from the bond, such as field turf, which was eventually paid for out of the district’s building fund.

“If you’re talking about hot-button issues, that’s one of them. People feel strongly either way about that,” Meraz said. “If you’ve got so much on athletics and extracurriculars that it’s starting to be detrimental to the whole bond surviving, you make some cutbacks.”

Meraz said carving down the bond issue decreased the projected tax increase to about 10.5 percent. Meraz said district supporters also looked more closely at voter rolls and emphasized to residents that school bond propositions require a supermajority of 60 percent of the vote in order to be approved.

“Strategy-wise, you’ve really got to make sure that everyone you thought would be a ‘yes’ voter got out and voted,” Meraz said. “You’ve got to make sure that people who are supporters aren’t taking these for granted and that they get out there and cast their vote.”

Ultimately, Elgin Schools ended up presenting the adjusted $36.9 million bond proposition on the March 2017 election ballot, where it was approved by voters with 61.43 percent support. The result has been the addition of the performing arts center, an athletic fieldhouse sitting by the north end zone of the football stadium, a state-of-the-art agricultural education building, classrooms and safe rooms.

“If you came out here today, I would brag about how beautiful and modern our campus is,” Meraz said. “But, these things like a performing arts center that seats over 1,000 people, we didn’t have that before.”

‘It’s the most pure form of local government’

McAdams attributed lower voter turnout for Atoka’s recent bond election to the fact it was the only item on the ballot. He said he felt the district could have done a better job at getting messaging about the bond issue out to community members.

“In the past, I’ve basically gone door-to-door to say, ‘This is what we have, this is what we need, this is what we’re going to do with it,'” McAdams said. “My mistake was, I felt like we’d done enough to where these people would really be very supportive of the school. I don’t think I got enough information out to everybody about exactly what we were going to do.”

A bond issue for Strother Public Schools failed in October when 77.95 percent of ballots were cast in opposition. However, only 331 total ballots were cast in the election. Voter data provided by the Seminole County Election Board shows 1,163 registered voters eligible to vote in bond elections for Strother Public Schools.

In some instances, low voter turnout has yielded positive results for school districts. Crutcho Public Schools, in east Oklahoma City, saw voters approve a bond issue in February with 93.75 percent of the vote. However, only 16 total ballots were cast in the election for the $920,000 school bond. As of Oct. 25, 880 voters are registered in the Crutcho district.

The district has a history of low voter turnout for bond elections. In 2013, Crutcho Public Schools was the subject of a Washington Post article after it had a $1 million bond issue approved with only five total ballots cast. In 2010, Crutcho had another $1 million bond issue approved with a total of 14 ballots cast. More recently, in 2017, a $820,000 bond issue was approved by receiving 67.86 percent of the 28 ballots cast in the election.

“I always say it’s the most pure form of local government,” said Meraz, the Elgin superintendent. “It’s a very pure and working form of government, because it’s right here. People can walk into my office, and they do sometimes, and voice displeasure. It’s not like we’re sending our dollars to D.C. or something. If you get out there and look at it, you’re paying some good taxes in the Elgin Schools. But we appreciate it, and it’s why we’re able to do the things we do and have the facilities we do. It’s not magic that makes this happens. It’s people contributing their tax dollars to make this a really great community.”