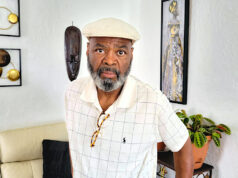

In 1988, Perry Lott was convicted of a rape and home invasion in Ada and sentenced to more than 100 years in prison. Thirty years later, in July 2018, after DNA evidence pointing to another man emerged, Lott walked out of a Pontotoc County courtroom a free man. Well, sort of.

The evidence that excluded Lott as a possible suspect emerged several years prior to his release, and he should have been sent home, free and clear, as soon as the truth about his case was known. Instead, it took years of legal wrangling, and even then he got out of prison on a compromised deal: Rather than drawing out the court battle even longer, Lott agreed to plead no contest to the charges and was released on time served. Despite the evidence of his innocence, Lott will be a convicted rapist for the rest of his days, ineligible for any compensation from the state of Oklahoma for his wrongful conviction.

Lott’s story and other high-profile cases where an Oklahoman’s guilt is called into question — such as with Julius Jones, Richard Glossip, Tommy Ward and David Payne — make it clear: Oklahoma’s court system has been an inadequate mechanism for dealing with questions of wrongful conviction.

Oklahoma has had dozens of folks cleared of their crimes and released from prison in the past, but in many cases it’s taken decades, and some came very close to execution. Only a lucky few have had hardworking attorneys advocating on their behalf as Lott did. Pro bono lawyers and innocence groups can take on only a small fraction of the cases brought to them by people behind bars who maintain their innocence.

Any number of legal advocates and defense attorneys in our state will tell you that our system is not designed to right wrongs after the initial trial.

Innocence commissions offer a better system

One path forward that Oklahoma should consider is the creation of a state innocence commission to review and investigate potential wrongful convictions. Such a commission would change the lives of the wrongfully convicted and demonstrate Oklahoma’s commitment to true justice.

The commission would be set up as an independent state body and would be tasked with investigating claims of innocence. Voting members would come from both sides of the aisle and could include former prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges and other criminal-justice stakeholders. There would be a formal process for vetting and evaluating the merits of innocence claims.

North Carolina has the only such commission in the country thus far, which provides a template for how Oklahoma’s commission could operate. Since 2007, the North Carolina commission has investigated more than 3,000 innocence claims and has exonerated 15 North Carolinians.

Looking forward

There has been commendable action on the issue of wrongful convictions in our state recently. HB 1551, by Rep. Kevin McDugle (R-Broken Arrow), passed a committee last year and is still eligible for a House floor hearing. The bill seeks to create a “conviction integrity unit” to investigate possible wrongful convictions among the state’s death row inmates. The unit would help shine some light on wrongful convictions and provide recommendations to the Pardon and Parole Board.

It’s a start, and the bill’s heart is in the right place, but the unit wouldn’t have the power to exonerate a wrongfully convicted Oklahoman, and ultimate power to free someone would be left in the governor’s hands during the existing clemency and commutation process.

On the other hand, the state is also at risk of taking steps backward. This session, Rep. John Pfeiffer (R-Orlando) is pushing HB 3903, which would actually bar the Pardon and Parole Board from hearing claims of innocence in death-row inmates’ commutation hearings, thereby reducing the ways for Oklahomans to escape unjust sentences.

Rather than adding layers to the existing criminal-justice bureaucracy, an independent, North Carolina-style innocence commission would have the teeth and structure to fairly and accurately evaluate innocence claims and take action where needed.

Creating such an agency will cost money, potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars per year. Those costs, however, would be offset every time an innocent person is released from our prison system. That’s a dollar-and-cents argument that may sway some.

The better argument: Regardless of the costs, our state needs to do everything we can to ensure the wrongfully convicted don’t spend another needless day behind bars.