While tensions between state and tribal leaders still hung in the air during Wednesday’s half of the 2022 Sovereignty Symposium, a pair of criminal law panel discussions centered on justice system challenges faced by tribal nations after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma decision and what long-term success will look like.

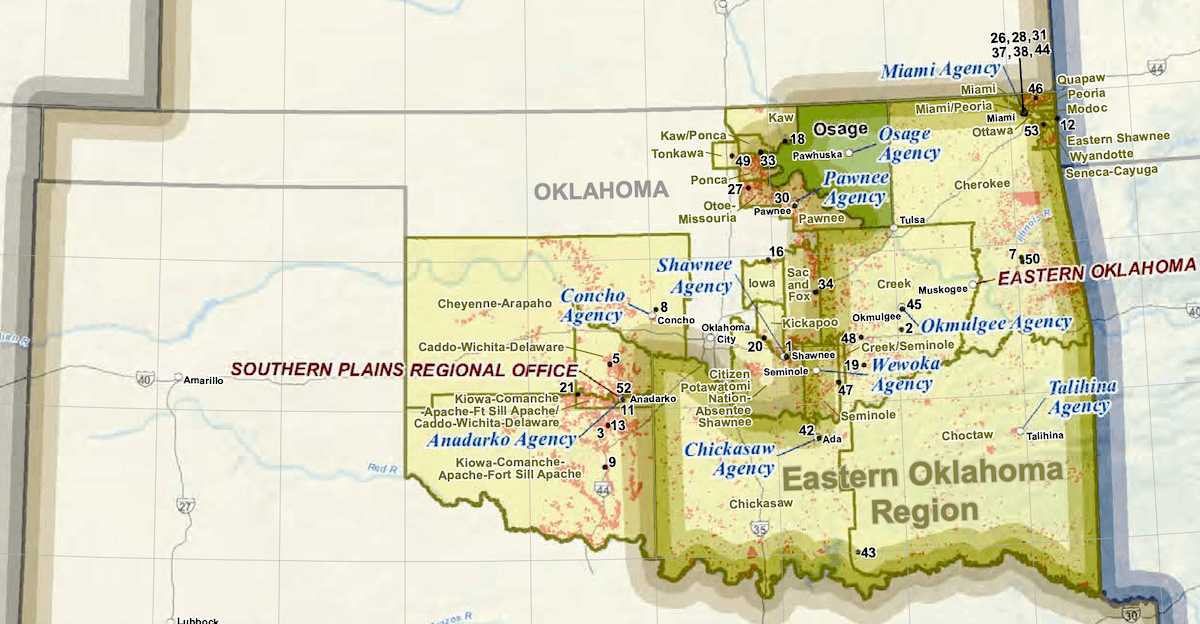

The Sovereignty Symposium is an annual conference featuring panels and ceremonies focusing on Oklahoma tribal and state relations, which have become more complicated following the SCOTUS ruling that functionally affirmed eastern Oklahoma to include a half-dozen Indian Country reservations.

Wednesday morning’s session featured a criminal law panel that showcased leaders from the six tribes whose reservations have been affirmed: the Muscogee Nation, the Cherokee Nation, the Chickasaw Nation, the Choctaw Nation, the Seminole Nation and the Quapaw Nation. Panelists spoke about the state of criminal justice in their nations.

Crimes committed by or against tribal citizens on reservations can only be prosecuted by the tribal nation or the federal government.

“It is a very important time that we are living in, a very interesting time that we are living in,” said Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr.

‘We are responsible for enforcing the law’

Tribal leaders all noted that the caseloads each tribe now has to handle have increased dramatically. The increase in cases has necessitated expansion and reform in tribal criminal justice systems.

“The number of cases that we currently have (…) we’ve increased by 800 percent (in the last year),” said Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton said.

Other leaders echoed similar figures about their caseload increases.

Chickasaw Nation Gov. Bill Anoatubby used his remarks to highlight his nation’s new Office of Tribal Justice Administration, which includes new staff in addition to the investigators and legal staff already on hand to process the additional cases on Chickasaw land.

“The law is made somewhere else. We are responsible for enforcing the law, and we’re responsible for doing the things necessary to get justice.” Anoatubby said. “So that’s what we’re focusing on. We’re not concerned about disagreements.”

Hoskin, the Cherokee Nation chief, also touted the expansion of his nation’s criminal justice capabilities.

“We have had a little over a year to build up a criminal justice system that, for the Cherokee Nation, is the largest in the state of Oklahoma, other than the state of Oklahoma’s (system), and we had a year to do it,” Hoskin said. “The state had more than a century to do it.”

Applause followed from the crowd when Hoskin paused and then said, “I think we’ve done well.”

Hoskin also asked for more money from the federal government to continue to expand the Cherokee Nation’s criminal justice system.

“This country ought to understand that there’s a cost, there’s a price to be paid, and the country ought to do it,” Hoskin said.

The Cherokee nation also plans to build a new courthouse and criminal justice building, which some originally thought would be a new jail.

Clinton Johnson, the acting U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Oklahoma, highlighted his own caseload increase and his office’s expansion in response.

Only tribal or federal governments can prosecute major crime cases involving a tribal citizen in Indian Country. State prosecutors no longer have jurisdiction when these conditions apply within reservation boundaries.

As a result, Johnson said the caseload in his federal district court has increased by “about 300 percent.”

In addition to money, many tribal leaders asked for people to come work in their criminal justice departments.

Cherokee Nation Attorney General Sarah Hill addressed recent law school graduates who might have been in the audience.

“Come to the Cherokee Nation, I have so much work for you to do,” she said, drawing laughter from the crowd.

Jeff Fife, the chief of staff for Muscogee Nation Principal Chief David Hill, said the nation’s criminal justice system expansions have been carefully considered.

“We’re working (…) to make a more inclusive criminal justice system,” Fife said. “The system we come from was always punitive. We’re being innovative. We believe there are other ways of adjudicating matters that help reintroduce people to our society and are not necessarily punitive in every regard.”

‘A promise made ought to be a promise kept’

Hoskin echoed comments that he made at last year’s Sovereignty Symposium.

“The McGirt case is about one central idea,” Hoskin said.” And that is that the government of the United States ought to keep a promise to Indian tribes.”

Despite the Supreme Court’s affirmation that Congress never disestablished the reservations in eastern Oklahoma, Hoskin noted that tribal sovereignty still has vulnerabilities.

“As strong as we are, as proud as we are of the progress that we have made in this state, in our nations, there is still a legal vulnerability,” Hoskin said. “And that is that the courts can make different decisions.

“We still have people walking into court asking that those promises be broken.”

Hoskin indirectly criticized Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, who has been blunt in his desire to overturn or limit the McGirt ruling’s jurisdictional impact.

“So when you hear tribal leaders from time to time stand up and proudly talk about what we’re doing, or stare down political leaders (…) you can understand why, on behalf of our people, we do that,” Hoskin said. “We know what this country has done to suppress some of the most powerful and effective governments this continent has ever seen.”

The morning panel also featured Trevor Pemberton, Gov. Kevin Stitt’s general counsel. Pemberton said Oklahoma has a history of state governors being opposed to tribes, saying that “each governor, regardless of their name, becomes the face of opposition to or conflict with competing sovereigns,” including tribal leaders.

Pemberton went on to use examples of other disagreements between state governors and tribal leaders in an apparent effort to normalize the current conflict.

“I have little doubt there will continue to be some disagreements the state will have with the tribes and vice versa,” Pemberton said. “That’s natural.”

Other panelists pushed back on this assertion.

“The tribes have approached things with a fundamental commitment to the rule of law,” said Stephen Greetham, senior counsel to the Chickasaw Nation.

Hill echoed the same sentiment.

“Gov. Stitt doesn’t have to like the decision in McGirt, but he has to accept the rule of law, as all people in this country must,” she said.

Greetham pointed out that, in the examples Pemberton used, tribal leaders worked through the conflicts. Now, he said, things are different.

“We don’t have any communication, any meaningful, substantive communication at the highest levels of state government,” Greetham said.

Moving forward, Greetham suggested that instead of fighting the courts, “the state of Oklahoma needs to be honest with itself about challenges on its side because none of [the tribes] are going anywhere.”

‘We’re all fighting for the same things’

Wednesday afternoon’s criminal law panel focused on the historical context for the McGirt decision and current related litigation.

University of Oklahoma law professor Taiawagi Helton spoke about the history of Indian law to show how the McGirt decision is just the latest court case reaffirming tribal sovereignty in the face of state opposition.

“There was a lot of resistance (in the 20th century) to the idea that there were tribal sovereigns in eastern Oklahoma,” Helton said. “And so as a result of that sort of disbelief (…) the state really kept pushing against an idea of tribal governance.”

Despite that, federal courts continued to affirm tribal sovereignty with cases in the 1970s and 1990s, Helton said. Now, the McGirt decision and related cases are the latest to do so.

Oklahoma County chief public defender Bob Ravitz highlighted some cases currently moving through courts related to the McGirt decision.

One of these cases, Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, is being pushed by the state to allow for “concurrent jurisdiction” for crimes committed against Indians by non-tribal citizens in Indian Country.

“This is gonna be a very close case that will affect tribal rights in every state in the union,” Ravitz said. “It totally imposes on the sovereignty of Indian tribes.”

Ravitz also said that the state seeking to take more power in this way is not new.

“I think some of us remember in history that states abusing Indian victims in their laws and depriving them of their property was something that occurred on a regular basis,” he said.

Ravitz referred to tribes being given money and jurisdiction to handle domestic violence cases because Oklahoma has “horrible” programs.

With the SCOTUS decision pending in the Castro-Huerta case, Ravitz said tribes could lose federal funding because, “Oh, the state will take care of that.”

Kay County District Attorney Brian Hermanson was critical of tribes’ abilities to handle the increased prosecutorial caseload after the McGirt decision.

“I don’t think there’s any question in my mind that there will be many cases that will go un-prosecuted under the system that we have under McGirt,” Hermanson said.

Later, when Muscogee Nation Attorney General Geri Wisner spoke, she called for unity and a recognition that everyone is working toward a common goal.

“What I’m hearing a lot of is an ‘us’ and ‘them’ kind of concept,” Wisner said. “When in reality, it is ‘we.'”

Wisner’s statement drew cheers from the audience.

Wisner went on to say that safety and peace are “common goals and ideas worth fighting for.”

“We’re all fighting for the same things,” she said.

The 2022 Sovereignty Symposium continues with more panel discussions and ceremonies scheduled throughout today.