It has been estimated that up to 1.2 billion people will be displaced by climate change worldwide by 2050. That means the number of refugees coming to the United States will likely explode, changing immigration from a challenge that has solutions to a predicament over which we have much less control.

In Oklahoma, we don’t have a stellar record in our treatment of immigrants, particularly those who are persons of color. For instance, a dozen years ago, Oklahoma passed what was, at the time, considered the strictest anti-immigrant legislation in the country, making it illegal to even offer a ride to someone suspected of being in the country illegally and allowing police to check people’s immigration status.

During my career as a teacher in Oklahoma, I often saw Latino students being treated poorly because of their race and stereotypes about immigrants. Yet I also saw instances of peace-making across racial lines brought about by honest and open communication. This approach can serve as an example for us as we look toward the mass migrations of the future.

Learning from young people

When I taught at John Marshall High School in the 1990s, many of my immigrant students and their parents said they had been welcomed in elementary school. But things fell apart in chaotic middle and high schools. They faced harassment from a small minority of students — many of whom had suffered their own traumas. (It was an instance of “hurt people hurt people.”) The immigrant students would keep their heads down in the hallways, pretending not to hear the taunts directed at them.

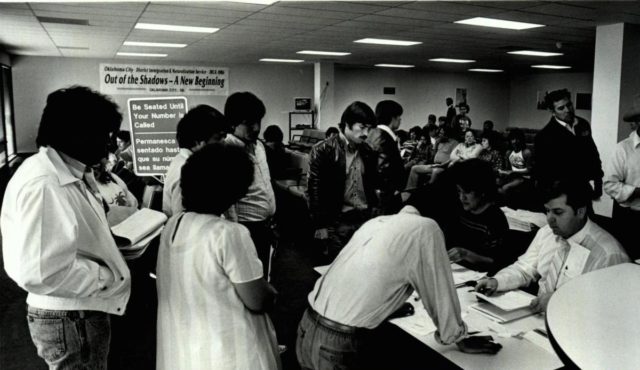

After the Oklahoma immigration law virtually invited police to stop Hispanic people at random, an immigrant student disappeared for three months. He later told the class that his family had been stopped by a policeman who promised to not turn them over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) if they got on their knees and begged. Many of his family members complied out of desperation, but they were deported anyway.

Yet, even in this tense atmosphere, there were examples of a better way of being. For instance, a turning point occurred when a white student driver accidentally hit a Black middle school student who had unexpectedly run across the street. The incident stoked racial tensions in the school that day as rumors began to circulate. But a student whom I’ll call Manuel — a Mexican immigrant who played on the football team — took it upon himself to investigate the facts and share the information with his teammates, who helped spread it through the school. Within hours, thanks to these cross-racial conversations, suspicions were quelled and the situation was much calmer.

A few weeks later, we were watching the climax in the movie Lone Star, where an immigrant survived the Rio Grande crossing, and her rescuer held out his hand, saying “Welcome to Texas.” The entire class was close to tears when a Black student with a special education IEP reached across the aisle, shook hands with his previously-deported classmate and said, “Welcome to Oklahoma.”

The importance of human connection

The state of Oklahoma, and the country as a whole, could take a lesson from these young people. In recent months, we’ve been seeing the heartless side of political and cultural tribalism, as governors from three states have used immigrants as props in political theater by shipping them to Northern cities and leaving them stranded there.

The resentment of newcomers is often seen as a natural result of the collapse of farms, economies and even life expectancy in “Trumpland.” But Ruth Conniff’s recent article Middle America: Getting Away from Toxic Partisanship, from The Progressive Magazine, offers another way to look at the situation.

In her article, Conliff describes driving around rural Wisconsin before the November midterms. She saw plenty of Donald Trump banners, but, talking to local dairy farmers, she also discovered more nuanced views of immigration.

Some of these farmers would regularly drive their Mexican workers down to Mexico to visit family and friends. So they got to see the workers’ tight-knit home communities and appreciate the investments the workers were making in those communities. Because they made this human connection, Conliff observes, these dairy farmers respected the “honorable work” of immigrants, which created an “antidote to toxic partisanship.”

Change can be frightening, but we don’t have to let our fears keep us from continuing to share the American Dream. And if we learn to respectfully communicate with all our diverse neighbors, we can all unite to deal with our planet’s greatest challenges.