With the upcoming conclusion of the public health emergency declared for the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated 300,000 Oklahomans could become ineligible for SoonerCare, the state’s Medicaid program funded with federal and state dollars.

The federal public health emergency declaration is set to expire May 11, but one of its impacts will hit days earlier. Beginning April 30, the state of Oklahoma will begin disenrolling those who — owing to income levels or other variables — are no longer eligible to continue receiving Medicaid through SoonerCare. The unwinding period will continue through the end of the year.

Nationally, about 23 million people became eligible for Medicaid from February 2020 to March of this year when the continuous enrollment period ended, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Those who enrolled were allowed to note economic hardships related to the pandemic, most commonly the loss of employment benefits through their jobs.

KFF estimates that between 5 million and 15 million Americans will lose coverage during the Medicaid unwinding period.

Oklahoma Health Alliance for the Uninsured executive director Jeanean Yanish Jones said the unwinding adds to an already significant problem of uninsured people in Oklahoma. Even after the passage of State Question 802 in 2020 that expanded Medicaid to cover adults up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, a large number of people in the state lack health care insurance, she said.

“When we had Medicaid expansion almost two years ago, there was a myth that it solved all of the uninsured and health care access issues, and that’s really very far from the truth,” said Yanish Jones, whose organization supports dozens of free and reduced-cost clinics in Oklahoma. “We have about 535,000 uninsured people, not even talking about the ones that are unwinding. And we have an additional almost 100,000 people that are undocumented that are also uninsured. And then you add in 308,000 unwinding, you’re getting close to a million people that don’t have [health insurance], which is about a quarter of our state’s population. So, this really is a crisis.”

Officials spreading word about Medicaid unwinding

To limit the number of Oklahomans who will become uninsured following the Medicaid unwinding period, the Oklahoma Health Care Authority has started the process of contacting those who may not be eligible through mailings. The agency has published a 34-page document outlining the upcoming changes.

Oklahoma Health Care Authority CEO Kevin Corbett said the state will unwind its Medicaid enrollment from the pandemic slowly and as precisely as possible.

“At the time before December when the Consolidated Appropriation Act came out, the public health emergency and the determination of that tied everything together, including something we call continuous coverage where we have currently a number of members who are on SoonerCare that — based on our initial review — do not meet eligibility requirements today,” Corbett said. “Income levels are exceeding it and all of that. So what the Consolidated Appropriations Act did was decouple continuous coverage and said that will end on April 1.”

Corbett said the bill does offer some temporary relief for those who are facing the elimination of their coverage.

“One of the things they did with that bill that they didn’t do previously was we said we will continue the level of federal support throughout the unwinding period,” he said. “It’s about a nine-month period. On the old public health emergency, money stopped when it was declared over. The money will continue over nine months on a declining basis. Everyone that has participated in the Medicaid program will benefit from the continuous money they will receive throughout the unwinding period.”

Of those who exceed the Medicaid income threshold, Corbett said people who are single with no children under age 5 and those who have not used their benefit during the emergency declaration will be unenrolled first. Families with children and those undergoing treatment for illnesses will be the last to be unenrolled. He said the goal is to make sure as many Oklahomans stay insured after the process is complete at the end of the year.

“What I’m trying to balance is that we have no gaps in coverage,” Corbett said. “Even though it may not be SoonerCare coverage, [they may be eligible for] a health plan — an employer plan — because some might be employed today and have that available to them. Maybe (we help them find access through) the federal marketplace.”

Corbett said that about 80 percent of people his agency has determined “are over the income levels” make “substantially” more money than the Medicaid threshold.

“[That] suggests there are things that have occurred in their life that make other things available,” he said. “It’s that small portion that we want to make sure they have coverage.”

First letters went out in February

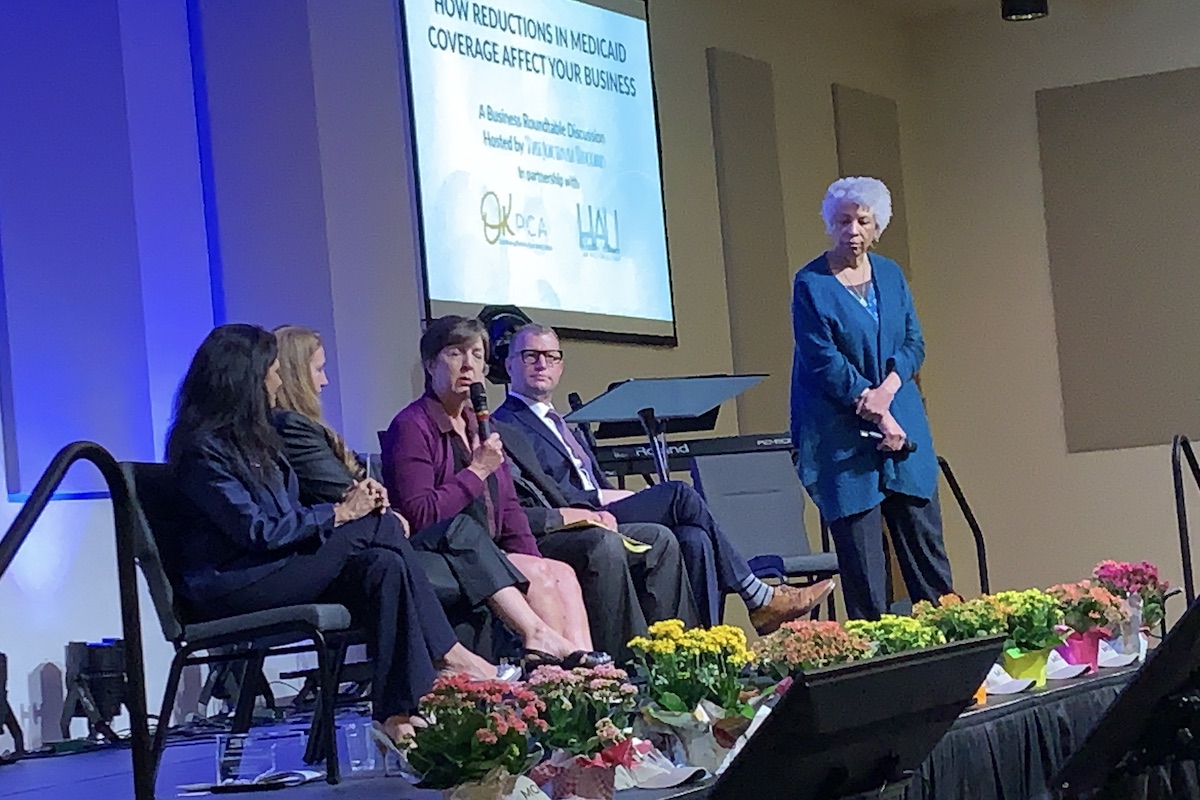

State Medicaid director Traylor Rains said the state began the unwinding process by sending out a letter to those who may be ineligible in February. Those letters were on purple paper.

“We wanted to make sure the letters stood out,” Rains said at a recent roundtable discussion on the Medicaid unwinding hosted by the Oklahoma Health Alliance for the Uninsured and The Journal Record.

Rains said those in Oklahoma’s Medicaid program — called SoonerCare — have been receiving benefits for the entirety of the pandemic no matter their employment or income status. Only those who died, unenrolled themselves or moved out of state saw their coverage end during the pandemic. In March, a second letter went out targeting those who were now considered ineligible for SoonerCare and were required to start a renewal request.

“We’re working with around 300,000 individuals,” Rains said. “Our federal partners have given us some broad guidelines for us to work within as we begin our unwinding, but we knew right away that we wanted to take a very compassionate and efficient approach to how we unwind the population and do these unenrollments.”

Part of that includes connecting those who will lose Medicaid with other options.

“We started running this population through various systems and queries to see who these folks are,” Rains said. “Have they ever used SoonerCare since they’ve been enrolled? What are their needs? Do they have chronic conditions? Are they receiving a lot of services through pharmacies. Do they have chronic conditions? We were able, through this process, to create a needs-based system for how we are targeting our nine-month unenrollment period. We chose nine months because we think it’s a realistic time frame to work with.”

Groups help navigate process

Legal Aid Services Oklahoma is also assisting those who face the loss of SoonerCare. Executive director Michael Figgins said the organization is available to help Oklahomans navigate the unwinding process. He said clients who use LASO often face income challenges.

“The clients that LASO sees, they are weary, they are exhausted, they have lots of fears,” Figgins said at the roundtable discussion. “They fear eviction. They fear tooth rot. They fear death. All too often I hear about loss, something being taken away from those who have very little to begin with.”

Figgins said those affected will come from all over the state and lack a backstop to prevent them from losing health insurance. The state currently has about 1.3 million people enrolled in SoonerCare.

“About one-fourth of them are at risk of losing SoonerCare,” Figgins said. “We are hoping that many of them reapply and many of them will be eligible. But until then, we’re still dealing with the unwinding, which sounds like a Stephen King novel. It sounds scary, and it is scary. There’s no safety net. Whether you live in urban Oklahoma or rural Oklahoma, you are going to be impacted.”

Figgins praised OHCA’s efforts to raise awareness about the unwinding of SoonerCare for those affected, but he said some of the responsibility rests with employers.

“The state is doing wonderful things,” Figgins said. “The state is responsible for all of the information that is going out. The applications, the renewal documents are in multiple languages. They are accommodating people who may not speak English and may not be able to hear or have issues with other disabilities to get the word out so everyone knows. They’re being told multiple times. As an employer, I need to do the same thing.”