A few years into his time at Edmond Public Schools, Daniel Khosrou Nayeri navigates the fifth-grade lunch hour without money in his account, selects the seat on the bus with the least risk of being heckled, and takes the most inconspicuous route home from Will Rogers Elementary.

“All Persians are liars and lying is a sin. That’s what the kids in Mrs. Miller’s class think, but I’m the only Persian they’ve ever met, so I don’t know where they got that idea.”

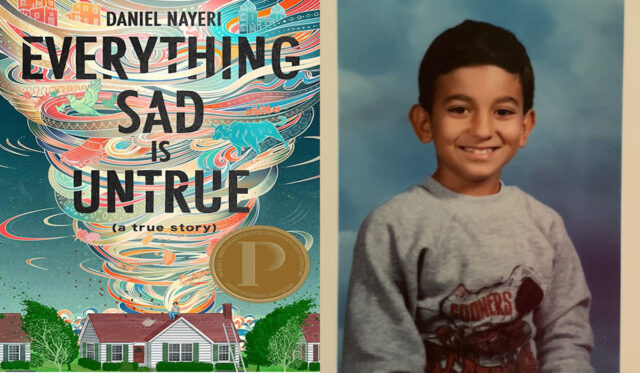

Originally from Iran, Nayeri arrived in Edmond in 1990 after his family fled owing to a fatwa issued against his mother. Two decades later, Nayeri is the author of a book — Everything Sad is Untrue: (A True Story) — that drops the reader into the middle of his childhood and narrates his experiences from his 12-year-old perspective.

As can be the case with pre-teen storytellers, Nayeri barely stops to take a breath. Throughout the book, he speaks directly to his fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Miller. He stops only to make sure Mrs. Miller is still listening, and while he is terrified he won’t be believed, Nayeri is even more afraid that he’ll lose his grip on his own story. Memories, or the lack of memory, about his grandfather “Baba Haji” inspired Nayeri to write the book.

“I haven’t been careless with [the memory of Baba Haji]. My heart clenches it like a fist. Like gripping a ball bearing as hard as you can,” Nayeri writes. “The fingers dig into the palm and you don’t even know if it’s still in there. The knuckles are white and you’re afraid it fell out and you didn’t even notice. You’re just clenching nothing until your nails cut into your palm and you bleed.”

Learning to play Nintendo and talk like an Okie

If anything, Nayeri hopes the reader will remember Jim and Jean Dawson, whom he describes as “so Christian” that they sponsored a refugee mom and two kids they had never met.

For six weeks after their arrival, Nayeri, his sister, Dina, and their mother lived in the Dawsons’ Edmond home. Nayeri recalls his early days in Edmond, eating sandwiches and Pringles and playing their grandson’s Nintendo.

“A refugee is someone who isn’t allowed back into their home country, and that’s certainly how I felt,” Nayeri said in an interview. “I still hope I can go back someday – though, at this point, it would only be to visit.”

In his book, Nayeri offers vivid details of navigating life in Edmond as a transplant from halfway around the world. He refers to adults as “grownies.” Some grownies just nod their heads and smile nervously when he answers their questions about where he’s from. A classmate dubbed Brandon Goff (not his real name) plays the role of villain that every good story needs, and he must be avoided. Kyle is Nayeri’s best friend. (His actual name is Blake, and the two remain best friends today.)

Observation became a necessity for Nayeri’s social survival.

“It’s easy to tawk lahk one them Okies. Just gotta loosen yer jaw a bit ’n’ never let yer teeth touch,” he writes. “Mostly, it’s slow and comfortable, imaginin’ you own a house and it has a porch and yer sittin’ on it.”

He refers to Edmond as the jewel of the Interstate 35 roadway. In jest, he writes: “Some people say Edmond, Oklahoma, looks like Italy in the springtime. Some people are idiots.”

Nayeri: ‘A patchwork story is the shame of a refugee’

Nayeri’s mother was a doctor who had a medical practice in Iran. He does not recall the specifics of where his mother worked once in Edmond, but he knew she spent long hours next to conveyor belts.

“I have never seen her not working. People in Oklahoma think this must be how refugees are — never sitting, never sleeping, like they have no knees and no dreams,” Nayeri writes.

The book is anchored in his day-to-day life as a 12-year-old boy, but it jumps to stories passed down through generations that tell of his royal lineage. These sections read like an epic.

“In Oklahoma we are the opposite of kings. Everything we own is inside a hard gray suitcase. It is mostly coats and papers,” Nayeri writes. “There is one squished shoebox full of photos that my mom guards, and cries over when she thinks we’re asleep.”

He has many memories.

At the encouragement of the grownies, Nayeri’s stuffed animal, Mr. Sheep Sheep, was “set free” in a field near an airport in Iran. (They knew Mr. Sheep Sheep would be cut open or confiscated by airport security, and they wanted to spare Daniel the trauma.) At preschool age, Nayeri experiences the turmoil of leaving his beloved companion in the dirt, and he notices that his father does not have a bag like the rest of them. Suddenly, he learns his father will not be fleeing the country with them.

“A patchwork story is the shame of a refugee,” Nayeri writes.

In Oklahoma, he finds solace at the Edmond library, surrounded by stories. On Saturdays, Nayeri and Dina are dropped off while their mother goes to work. Nayeri develops a strategy for passing days at the library, which offers access to a wide range of content, from pop culture to poetry.

Nayeri makes the acquaintance of Helen Brown, the librarian and kindest person he had ever met. He is astonished when she says he can check out 35 books at a time and keep them for two weeks. His time at the Edmond library, in the company of books, would prepare him to make a career out of storytelling.

‘I realize just how world-class my education was’

Before arriving in Edmond, Nayeri was trilingual. The family fled Iran and sought asylum in Dubai and Rome before settling in the United States. Along the way, Nayeri’s mother ensured her children were educated. Nayeri entered the Edmond Public Schools system as an 8-year-old.

Though his early days in Oklahoma were not without struggle, he speaks highly of his experience in Edmond Public Schools.

“I still wear my [Edmond Memorial High School] ball cap with pride. The older I get, the more I realize just how world-class my education was,” Nayeri said. “Last summer, I drove my son by the school, pointed out all my favorite spots, and sang our fight song for him.”

After graduating, Nayeri went to New York University and studied writing.

Today, Edmond Public Schools has 334 immigrant students and 95 refugee students enrolled. Andrea Wheeler, the district’s educational services coordinator, said that in 2021 the district prepared to accept an influx of refugees from Afghanistan when thousands fled the country after the Taliban seized back control, almost two decades after they were ousted by a U.S.-led coalition. The district formed a committee to provide cultural sensitivity training and materials for teachers who would welcome refugee students in their classroom.

“We encourage educators to be aware of the stories and be conscientious of their reactions,” Wheeler said.

A key figure in Nayeri’s book, Mrs. Miller was the name of an actual EPS teacher who has since died, but her character serves as an amalgamation of several teachers Nayeri had during his time in school. Overall, Mrs. Miller attests to a teacher’s power in the life of a student.

“I was awfully grateful to my teachers for not making me the subject of special attention,” Nayeri said. “I often found myself unsure of the instructions on a project, and I wouldn’t have dreamed of raising my hand to ask. I’m thankful I had the sort of teachers who came by discreetly and helped me out.”

Nayeri speaks highly of Edmond and his home state.

“I am convinced that Edmond, Oklahoma, is one of the best places for anyone to end up,” Nayeri said. “Edmond was the kind of high-trust community that seems almost too good to have ever been true. Of course, there are knuckleheads like some of the kids in my book — including myself — whose behavior would scandalize the internet’s sensibilities. But there are too many good people to count.”

Nayeri’s family had various living arrangements in Edmond, from the Dawson home to the Brentwood apartments and later a neighborhood home. He tells a story of being outside in the pouring rain, nailing down shingles during a tornado warning. The family had no concept of how to deal with the situation, and the scene is creatively illustrated on the cover of Everything Sad is Untrue with a vortex of other symbols from the story.

“You probably don’t know this, but Oklahoma is called Tornado Alley, and also the Buckle of the Bible Belt, which means it’s a great place to hide,” he writes.

‘I don’t know that many people who want to be getting without also giving’

These days, Nayeri lives with his wife and son in New Jersey. He is a publisher and author of several books for young readers. He has been a writer for several short films, a miniseries and a film in pre-production. Earlier this summer, he announced a film and television production company called PlotNaut.

Did you know?

Released in 2020, Everything Sad is Untrue: (A True Story) has won the Michael L. Printz Award, the Christopher Medal, and the Middle Eastern Book Award.

Most recently, Nayeri published The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams, and he has announced plans for a new book to be released in the fall of 2025 under the title: A Knot is Not a Tangle. He called it the story of an Iranian boy who learns to see beauty and purpose in the imperfect while weaving a new family rug with his grandmother.

For young refugees and immigrants currently acclimating to American schools and new communities, Nayeri’s words may impart a necessary comfort in an uncomfortable world.

In recent years, EPS employee Erica Fain has created bags with various resources for immigrant and refugee families. She observed a valid fear and misunderstanding of weather among these families.

“I created a map so refugee families know where they are,” said Fain, Edmond Public Schools’ English language learners content specialist. “I think about them watching the weather or a tornado warning and having no idea where they were in proximity to the actual tornado.”

Nayeri says he is not at all surprised that Edmond Public Schools leaders have raised the standards and are intentional about their relationships with refugee and immigrant students.

“I don’t remember any resources in the sense of formal ESL courses, acclimation programs, or anything like that,” Nayeri said. “Churches remain the best source in a community like Edmond for that sort of personal connection and help. We certainly had that.”

Nayeri asserts that connections do not have to be complicated.

“The answer to almost all social awkwardness is a ball. Helping kids recognize that they can share an interest, whether or not they speak the same language, is a gigantic step toward helping both parties understand how to make friends,” Nayeri said. “These things require almost no language or sensitivity training and would do wonders to help a refugee kid across all the other metrics that adults care about.”

He said that forming connections is also a two-way street.

“I also think well-meaning people will consider all the ways they can help a refugee while missing the opportunity to ask how the refugee could help them,” he said. “By that I mean being useful to someone, bringing their talents to bear, or sharing some part of themselves. These are all moments that, generally speaking, people appreciate. I don’t know that many people who want to be getting without also giving. I think if someone was so inclined, they’d be most helpful to facilitate that sort of exchange.”

When offering advice to a refugee or immigrant student, Nayeri now speaks with conviction.

“Someday, all your weaknesses will be strengths,” he said. “The difficulties you encounter now will become the skills you cherish about yourself in the future. Someday will not be soon.”