The last two survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre sat before the Oklahoma Supreme Court today as their attorneys argued against the dismissal of their public nuisance and unjust enrichment claims filed against the City of Tulsa and other state actors for their role in the 1921 massacre.

“The question before the court is very simple, straightforward and procedural in nature,” said Damario Solomon-Simmons, the lead attorney for survivors of the massacre. “We want this court to reverse the trial court’s decision and remand us back to start discovery as soon as possible, as time is of the essence for these two 109-year-old survivors who are with us today.”

Since 2020, Solomon-Simmons has represented Lessie Benningfield Randle and Viola Ford Fletcher, the remaining survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, a two-day conflict in the middle of 1921 that left an unknown number of people dead, predominantly in the Greenwood area, which was one of America’s must affluent Black communities before white mobs burned it to the ground.

The two survivors’ lawsuit argues that the City of Tulsa, the Tulsa Regional Chamber, the Tulsa County Board of Commissioners, the Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office and the Oklahoma Military Department all contributed to a public nuisance for their roles in the massacre. In 2023, Tulsa County District Court Judge Caroline Wall dismissed the lawsuit with three orders that survivors appealed to the Supreme Court.

With Benningfield Randle and Ford Fletcher seated to his left for Tuesday’s nearly 90-minute hearing, Solomon-Simmons hammered home a long-standing criticism in Tulsa’s Black community.

“You have defendants who have never ever been held legally responsible for the massacre, and to this very day these defendants deny they perpetrated the massacre. They deny that they created a public nuisance, they deny that they have any legal responsibility to clean up the public nuisance — the blighted neighborhood of Greenwood — that they created,” Solomon-Simmons said. “They’ve escaped liability for 103 years.”

The plaintiffs’ unjust enrichment claim also relates to the government actors and regional chamber’s ongoing actions. The briefs allege that, since the massacre gained broader public awareness over the last two decades, the defendants have promoted tourism as a way to “utilize the story of the massacre and the ‘triumph’ of its survivors and descendants to obtain funds from wealthy donors.”

The survivors’ brief points to the $30 million dollar Greenwood Rising History Center as part of a “cultural tourism district” intended to generate tax and business revenue for the lineage of the same institutions that perpetrated the massacre.

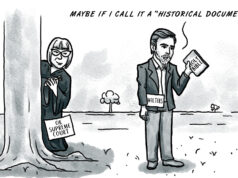

Despite the heavy claims behind the lawsuit, Tuesday’s oral arguments — which you can view online — centered on procedural issues: whether survivors of the massacre have identified an adequate remedy for the harm.

‘I share your confusion as to exactly why she dismissed the case’

After Solomon-Simmons presented his argument, attorneys for the Oklahoma Military Department, Tulsa Regional Chamber, City of Tulsa, Tulsa County Board of Commissioners and the Tulsa County sheriff each were allotted time to argue their positions. (The Tulsa County Board of Commissioners and Tulsa County Sheriff Vic Regalado shared an attorney and time for their oral arguments.)

Oklahoma Solicitor General Gary Gaskins, representing the Military Department, argued that claims against the state agency were barred by sovereign immunity, that the two survivors were not specially injured, and that any rioting by Oklahoma National Guardsmen occurred outside the scope of their employment.

With Gaskins discussing grounds for dismissal that did not appear in Wall’s unusual trio of orders, Justice James Edmondson said the district court’s ruling was confusing.

“Are you suggesting that [the district judge] ruled erroneously and we can order another way we can uphold her?” Edmondson asked. “Frankly, I share your confusion as to exactly why she dismissed the case.”

Justice Noma Gurich appeared skeptical of Gaskins’ argument that there was no special injury to the plaintiffs.

“Did the military attack other neighborhoods in 1921?” Gurich asked.

Gaskins responded that sovereign immunity would shield the Military Department from liability.

John Tucker represented the Tulsa Regional Chamber and argued that plaintiffs’ petition failed to state a claim and that the survivors lacked standing.

“These issues are all plainly describing issues of inequality, discrimination, economic disadvantage and related issues, but they are not nuisances as they relate to these plaintiffs,” Tucker said.

Kristina Gray represented the City of Tulsa and focused on arguing latches, or that the delay in bringing the litigation has unfairly prejudiced the defendants.

Keith Wilkes represented the Tulsa County Sheriff’s Office and the Tulsa County Board of Commissioners, pushing back on the argument that north Tulsa’s current blight is a direct result of the 1921 massacre.

“Counsel for the appellants claim Greenwood was never rebuilt after the Tulsa Race Massacre. While in line with their claims, this assertion is simply not supported by history,” Wilkes said. “It is (Scott) Ellsworth who writes the rebuilding of Black Tulsa after the riot, particularly that of ‘Deep Greenwood,’ is a story of equal importance as the riot itself.”

Wilkes placed blame for inequality in north Tulsa on migration, big retailers and the interstate highway system that built the Interstate 244 inner-dispersal loop right through Greenwood.

Solomon-Simmons emphasized in his closing comments that a Supreme Court decision in his clients’ favor would only allow the case to proceed, not guarantee a win.

“We need discovery in this case,” Solomon-Simmons said, referring to the stage of litigation where opponents must provide access to records relevant to the litigation. “If we get discovery, we can prove [our claims].”

What constitutes a ‘public nuisance’?

Public nuisance law is old, and in Oklahoma it has not changed much since statehood. A public nuisance “affects at the same time an entire community or neighborhood, or any considerable number of persons, although the extent of the annoyance or damage inflicted upon the individuals may be unequal.”

Oklahoma’s public nuisance statute was enacted in 1910 (copied from an 1887 Dakota Territory statute) and has only been amended once since passage to exempt some agricultural activity.

Whether public nuisance claims are considered torts has historically been a matter of some disagreement. Tort suits against governments are governed by the Governmental Tort Claims Act. Traditionally, governments are immune from civil liability under the doctrine of sovereign immunity, but the GTCA that passed in 1985 waived sovereign immunity if plaintiffs follow its requirements.

The county sheriff, board of commissioners, Oklahoma Military Department and City of Tulsa have all argued in case briefs that the GTCA applied to the survivors’ lawsuit, alongside its one-year statute of limitations for bringing a claim. Attorneys for survivors argue that public nuisance claims are not torts when equitable relief is sought instead of monetary damages.

In the case brought by Benningfield Randle and Ford Fletcher, they are requesting abatement — ending of the harm from the nuisance — in the form of rebuilding housing and businesses, the return of land to victims of the massacre, and improvements in the Greenwood District. They are not seeking direct monetary damages.

While the issues in the question before the Supreme Court are largely procedural, the historical weight of the proceedings was addressed at the end of the hearing just before adjournment.

“When I went to high school, I knew about the Trail of Tears, I knew why Chief Pleasant Porter wanted prohibition, and the Constitution. But Greenwood was never mentioned,” Justice Yvonne Kauger said. “I think regardless of what happens, you’re all to be commended for making sure that it will never happen again, that it will be in the history books.”