In December, Gov. Kevin Stitt issued Executive Order 2023-31, which prohibits Oklahoma institutions of higher education from using state funds to “grant or support diversity, equity, and inclusion positions, departments, activities, procedures or programs to the extent they grant preferential treatment based on one person’s particular race, color, sex, ethnicity, or national origin over another’s.” The order also required state colleges and universities to conduct a review of their diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and activities to ensure they do not violate the executive order and to modify or eliminate them if they do. Institutions and agencies are also required to submit a report about their DEI programs by May 31.

Stitt’s order followed an interim study by the Oklahoma Senate in which representatives from conservative public policy organizations such as the Goldwater Institute and The Heritage Foundation provided information critical of DEI programs. Sen. Rob Standridge (R-Norman), who requested the study, had also authored multiple bills for the 2024 legislative session to eliminate DEI programs from the state’s colleges and universities.

Critics responded that eliminating these programs threatens needed “safe and inclusive” spaces for “minority and marginalized communities on higher education campuses,” amounts to an effort to “erase Native Americans from history,” and risks future economic development in the state. The presidents of the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University issued statements referring to Stitt’s action as a “step backwards” and affirming their “passion to do what’s right.” (OU went a step further, initially claiming the order was “eliminating” its DEI programs. Later, OU’s president said its DEI programs would simply be rebranded.)

This debate forces us to address an important question: How can we ameliorate past injustices without hampering academic freedom? As faculty members from two of our state’s institutions of higher education, we believe we are in a unique position to offer some important insights on this topic.

Rectifying past discrimination

It should be no secret that Oklahoma has a history of legal discrimination against minorities. Senate Bill 1, the first piece of legislation introduced in the Oklahoma Senate, established racial segregation in public transportation. Similarly, a constitutional amendment instituting a “grandfather clause” was passed soon after statehood to limit voter eligibility among Black residents and prevent African American Rep. A.C. Hamlin (R-Logan County) from being reelected.

The state’s history of discrimination can also be found in its institutions of higher education, where two civil rights cases opened up higher education to minorities and formed the foundation for the more famous case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. Both Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents (1948) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950) saw the U.S. Supreme Court strike down racial segregation in higher education programs in Oklahoma.

While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned legal discrimination in higher education, many recognized that merely eliminating the prior-existing restrictions would not sufficiently undo the past discrimination against racial, ethnic, religious and gender minorities. Affirmative action programs emerged in higher education to broaden access to historically discriminated-against groups.

At their best, DEI programs continue to expand educational opportunities to groups historically discriminated against by providing them the resources with which they can be successful in college. Critics of DEI programs would do well to recognize that the task of making our university campuses a true reflection of our diverse society is still unfinished business and that intentional institutional efforts are still merited.

Enforcing ideological commitments

However, sometime in the 2010s, DEI programs began to go beyond this core mandate of outreach and support to marginalized communities, with some insisting upon enforcement of ideological commitments that are largely incompatible with the central mission of higher education: the pursuit of knowledge, and the freedom of speech and academic inquiry upon which that pursuit relies.

Recent episodes at Stanford Law School, Hamline University, and Harvard University — among many others — demonstrate a growing hostility to free speech and the freedom of academic inquiry that has emerged on college campuses. In addition, “bias response teams,” which have developed under DEI auspices at universities across the U.S. (see MIT, the University of Maryland, and Smith College as examples), have been active in encouraging students to report (often anonymously) any perceived comments by other students or faculty that they may find “offensive.” The offenders sometimes endure investigations without ever being told what they were investigated for and without the protections of due process. The imposition of “diversity” statements in faculty applications is another example of an attempt to enforce a specific way of thinking upon college faculty.

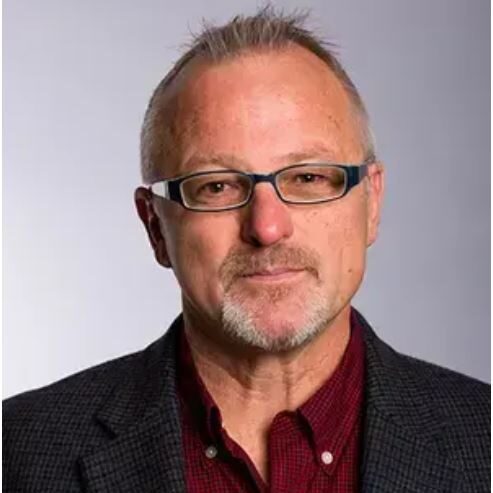

Oklahoma is not immune to this phenomenon. The 2018 case of Professor Brian McCall of the OU Law School stands as one of the more egregious examples. Branded “homophobic” and “sexist” by The OU Daily, McCall was forced out of his positions as associate dean for academic affairs and associate director of the OU Law Center for controversial passages in his 2014 book To Build the City of God: Living as Catholics in a Secular Age, which was aimed at an audience of fellow-traditionalist Catholics.

While we both may disagree with the sentiments expressed in McCall’s book, these beliefs alone provide no grounds for dismissal from administrative positions. They are views held by millions of traditionalist religious adherents, including Muslims and Orthodox Jews who also happen to be our fellow citizens. McCall lost those administrative positions despite an investigation into the matter finding “no evidence of workplace harassment or discrimination.” However, OU eventually settled a lawsuit filed by McCall over the matter. While it does not appear that OU’s DEI office was involved in the campaign against McCall, DEI offices across the nation have been associated with similar activities.

In their 2018 book, The Coddling of the American Mind, authors Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt coined the term “Safetyism” to describe the rationale that campus administrators often use to restrict free speech. According to Lukianoff and Haidt, students have come to expect protection from opinions and ideas that make them feel “uncomfortable.” The authors also chronicle the emergence of an environment where words are considered violence and in which students feel justified using actual violence to stop a campus speech with which they disagree. Safetyism is a rationale that has been used to suppress speech coming from the left as well as the right (and center).

In the name of diversity and inclusion, viewpoint diversity sometimes has been squelched. This constriction of free-speech rights on college campuses is one that DEI supporters have been loath to acknowledge. However, the role some DEI administrators have played in the shrinking of academic freedom should be recognized and addressed.

How to move forward

How do we make our student bodies more diverse without compromising the values of free speech? We advocate an intentional, institutional commitment to diversity and inclusion, which is data-driven and which rejects zero-sum logic.

Harvard economist Roland Fryer argues DEI efforts should be based upon data rather than poorly-informed intuitions. Researchers such as Fryer and others are showing the way by applying the tools of social science to better understand what raw gaps in employment, educational achievement and income do and do not tell us about bias at both the individual and institutional levels.

Interestingly, data suggest either that DEI programs have no established impact on bias, that the impact is not long-lived, or that the impact is, in fact, negative. With the empirical work indicating that how we promote diversity and inclusivity is ineffective and possibly counterproductive, perhaps we should reevaluate what we are doing.

In addition, our efforts must get beyond the notion that we operate in a zero-sum environment. Broadening access to educational opportunities does not have to mean others are excluded from that opportunity. Opponents of DEI institutional efforts need to realize that we all benefit from the creativity and talent from others and should not feel threatened by efforts to recruit students from different socioeconomic backgrounds, racial and ethnic backgrounds and religious backgrounds. Having intelligent and intellectually curious students from all walks of life improves our campus environments and ultimately the societies those campuses serve.

However, universities and institutions that keep the DEI acronym should handle the term “equity” with care. The traditional understanding of equity considers it as providing disadvantaged groups with the tools they need to succeed — a notion that merits broad support. However, the zero-sum context in which the term is too often understood and implemented presumes that for those same disadvantaged groups to be successful, those from other groups must lose or be prohibited from exercising their rights. Controversy over placing equity considerations above academic standards at the K-12 level and in higher education has received pushback, as such efforts may have actually harmed the very students they were intended to help. As interpreted by some, the principle of equity can become problematic if it presumes the only just outcomes are “equal outcomes.” And some proponents of equity presume any differences in group outcomes to be the result of bias. As Fryer argues in the article referenced above, this is both anti-science and counterproductive.

Finally, we also endorse Harvard Professor of psychology Steven Pinker’s recommendations for protecting academic freedom and the Heterodox Academy’s values of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity and constructive disagreement (called the HxA Way). Ultimately, we do not believe the goals of diversity and inclusion are incompatible with free speech or protections for academic inquiry. In fact, rather than sacrificing one to the other, we must recognize that these goals can and should be mutual.

(Editor’s note: The views expressed in this commentary are solely the views of the authors and do not represent the views of their academic institutions or Heterodox Academy, of which both authors are members.)