A proposed five-year consent decree to settle a class-action lawsuit and reform how Oklahoma provides competency restoration services to mentally ill criminal defendants has been filed by plaintiffs’ counsel and Attorney General Gentner Drummond, but Gov. Kevin Stitt and the state’s mental health commissioner say the proposal has lacked due diligence and will improperly involve lawyers in clinical practice decisions.

Drummond’s preference for settling Briggs et al v. State — a lawsuit his office called “indefensible” in a memo provided to legislative leaders — spurred a $4.1 million budget line item in this year’s appropriations bill for the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

As proposed, the settlement must be accepted by U.S. District Judge Gregory Frizzell and approved by the Oklahoma Legislature.

If both of those actions occur, all parties and a trio of selected “consultants” would have 90 days to prescribe a “plan” for meeting goals of the settlement, which would require significant but unknown state expenditures for mental health services, establish a multi-million-dollar annual fine structure for when ODMHSAS violates a “maximum time” provision, and cap plaintiffs’ attorney fees and litigation costs at roughly $742,500.

“If this lawsuit proceeds, there is no doubt the state would be facing significant litigation risk that could cost taxpayers dearly,” Drummond said in a press release Monday. “This settlement, the result of months of extensive negotiations, will initiate important improvements and fix a broken system that has been a travesty of justice.”

But behind the scenes, state leaders have been less united about how and when to move forward with addressing the patient backlog at the Oklahoma Forensic Center in Vinita, the only state facility fully equipped to provide secure inpatient competency restoration services. The hospital also houses criminal defendants found not guilty by reason of insanity or mental illness until such a time that they are released from custody, a responsibility that has allegedly diminished OFC’s “competency restoration” capacity.

The settlement proposal announced Monday — first by plaintiff attorneys at Frederic Dorwart and then by Drummond’s office — would establish a 21-day maximum wait time for the state to provide competency restoration services to a county jail detainee deemed incompetent by a court. In most cases, competency restoration services involve providing anti-psychotic medications.

Stitt issued a statement late Monday calling the proposal “a bad settlement” and questioning Drummond’s motives.

“We have to ask why the AG is forcing a settlement that will result in an immediate win for the plaintiffs’ attorneys at the expense of the Oklahoma taxpayers,” Stitt said.

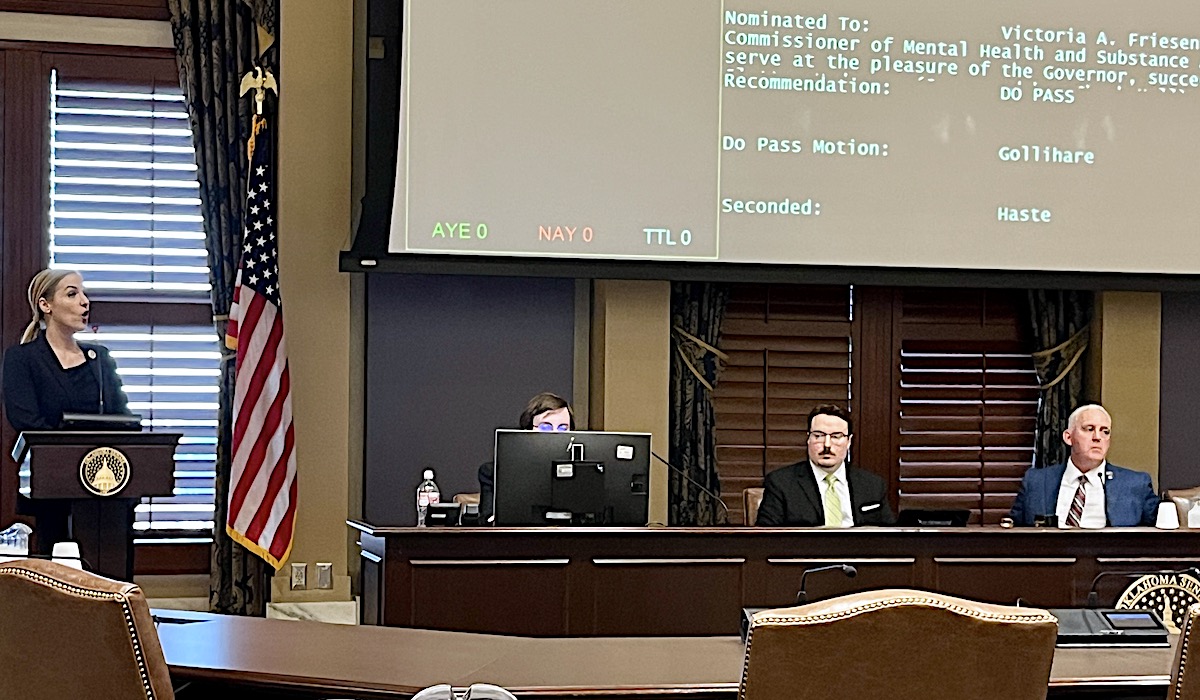

The governor appointed new ODMHSAS Commissioner Allie Friesen in January, a decision he said he made because the agency was “due for positive change, and she has brought that in short order.”

“She is turning things around, and it makes no sense to saddle this agency with a bad settlement,” Stitt said. “I hope AG Drummond will amend his settlement agreement and give Commissioner Friesen a chance to make a change in the behavioral health system.”

In an interview late Monday, Friesen said she met three times with Drummond in recent weeks to request more time for her team to continue analyzing and formulating the particulars for how to improve provision of competency restoration services in Oklahoma, something she said is needed.

But as outlined in the proposed consent decree filed by Drummond and plaintiffs’ attorneys, those details would be worked out after the fact by ODMHSAS, Drummond’s office, class (or plaintiffs) attorneys and a trio of expert “consultants,” who will be paid $450 per hour for their work over five years of the decree.

Friesen bristled at the proposed consent decree’s timelines and called the situation “frustrating.”

“He gave us grace in allowing us to come to the table,” Friesen said of Drummond. “But the timelines have been extraordinarily tight. So when I say we need time to identify the root cause, we need more than a week. We need at least nine months for our teams to get in there and to understand what we’re dealing with, and that was our ask. (…) It is frustrating for us to not be able to do this the way that Oklahomans deserve, because what I don’t want is us in five years to look up and to still be in the same place that we are today.”

During her first few months on the job, Friesen said one of her priorities has been “to reestablish a relationship” between ODMHSAS and Drummond’s office.

“I’m not privy to the details of what did or did not happen, but the attorney general made it very clear that this settlement agreement or consent decree — basically that someone was going to be punished for what had or had not been done,” Friesen said. “Again, I’m not privy to the details, but that was kind of the dynamic I came into and have been pushing against.”

Despite not fully understanding what has or has not happened with the litigation since it was filed in March 2023, Friesen said she does not have confidence in the consent decree submitted to the federal court Monday.

“As it’s written today, there is involvement of class counsel in clinical decisions, and I have made it very clear to the Attorney General’s Office that attorneys should have no place at the table when it comes to making clinical decisions and how we are going to apply clinical practices. So my ask has been that we let the clinical experts make the clinical decisions and let the attorneys make the legal decisions,” Friesen said. “I’m not confident that this is a good option for Oklahomans. It’s not, because there is very likely a significant waste of taxpayer dollars without having the ability for us to make wise and strategic decisions about how our dollars should be spent.”

‘Everyone who has looked at this knows the system is broken’

If Stitt and Friesen are worried about a “waste of taxpayer dollars,” Drummond and the plaintiffs’ attorneys — who filed the class-action lawsuit as “next friends” of incapacitated and disenfranchised mentally ill Oklahomans — argue that the state attempting to defend the lawsuit would be a major mistake.

“There’s a commitment to increase forensic beds. The plan has to be made within 90 days to determine how many beds and how they’re going to be sourced,” Paul DeMuro, the lead plaintiff attorney with Frederic Dorwart, said Monday. “There is a commitment to improved and increased staffing levels and training for key personnel, and standardized qualifications for people who are performing competency evaluation.”

Oklahoma leaders have been forced into improving state services for vulnerable populations before, most recently regarding how the Department of Human Services handled foster care services. A 2011 settlement in D.G. v. Yarbrough established the Pinnacle Plan, which required annual reporting about foster-care-system improvements and mandated monitoring from “co-neutrals” over the next decade.

DeMuro and other Frederic Dorwart attorneys represented plaintiffs in the case, and Frizzell also served as the judge who affirmed the plan, which has been lauded for its process improvements but criticized for its third-party payments.

“One of the things that is good about this settlement is that the attorney general has the foresight and wisdom to focus on a solution rather than deny there is a problem and end up like we did in the foster care litigation and end up with the state having a multi-million-dollar legal bill in addition to having to implement the changes,” DeMuro said. “He is to be commended, as is the new commissioner, instead of having five years of protected litigation.”

In an interview Monday, DeMuro implied that Friesen was supportive of the consent decree proposal.

“This has been contentious, and we have disagreed on what the right approaches are in some cases, but we have been focused on the solution and not the problem,” DeMuro said. “That’s the real headline here. That because of the approach taken by the attorney general, we’ve been focused on the solution and not the problem. Everyone who has looked at this knows the system is broken. So instead of spending five years focused on that, we are focused on the solution.”

Friesen, however, argued that ongoing efforts to improve staffing and service capacity — she said 80 additional beds are being brought online in Vinita — should be allowed to unfold as her staff uses data to find the “root cause” of the systemic issues.

“Moving forward, regardless of how this plays out — agreement or no agreement — there are so many stakeholders here who have to hold up their end of the deal. There’s the courts, there’s the DAs, there’s the sheriffs, we have the jail staff, we have our employees (at ODMHSAS), we have our contracted partners,” Friesen said. “There are so many players in this game, and that is part of why we want to do it the right way and understand the potential pain points across all of those stakeholders so we can arrive at a durable solution and not just throw spaghetti at the wall and see if it sticks.”

One particular problem Friesen has with the proposed consent decree is its prescription of what programs will and will not be allowed or required for ODMHSAS.

“Within 90 days after the court enters this consent decree, defendants, in consultation with class counsel and the consultants, shall develop and begin to implement a plan, to be approved by the consultants, for a pilot community-based restoration treatment program in Tulsa County, Oklahoma County, McIntosh County and Muskogee County,” the consent decree states on Page 23. (Page 43 of PDF).

None of those proposed restoration programs would be based in western Oklahoma communities, an issue that could irritate rural lawmakers west of Interstate 35.

Meanwhile, the proposed decree would require ODMHSAS to shut down its existing “in-jail competency restoration” program statewide, which launched in early 2023.

“Plaintiffs dispute that defendants ever implemented a legitimate state-wide competency restoration program consistent with generally accepted professional forensic standards,” the consent decree states. “Within 60 days after the court enters this consent decree, the department shall wind down and cease operating its alleged state-wide in-jail competency restoration program.”

Emphasizing that plaintiffs alleged there were at least 300 people waiting in county jails to be transferred to Vinita for competency restoration services when the litigation was filed last year, DeMuro said ODMHSAS rolled out a “sham” statewide jail-based restoration program.

“We contended that jail-based restoration program was a sham designed to conceal the fact that there was a huge waitlist of people languishing in county jails waiting for restoration services,” DeMuro said.

Friesen, however, said the numbers tell a different story, as evidenced by the fact that the proposed consent decree would require ODMHSAS to begin in-jail competency restoration services in Tulsa County and “one other county” within 90 days.

“We have restored, as of last week, 196 lives to competency since beginning of 2023,” Friesen said. “That is almost 200 lives that were restored in a jail setting that did not need to be transferred to OFC.”

Tulsa County being the only named participant in the consent decree’s proposed in-jail competency restoration program is a bit ironic, Friesen said.

“We have not been allowed to provide jail-based services in Tulsa County, and again that predated my arrival,” she said.

She said the consent decree’s proposal that would require “cessation” of existing jail-based restoration services “feels like we are shooting ourselves in the foot.”

“We have a problem, which is our citizens of Oklahoma who are potentially or allegedly ‘languishing’ in jail, and we have the capability as the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services to regain them to competency in the jail-based setting,” she said.

Beyond the confusing nature of the consent decree mandating that ODMHSAS stop providing jail-based services in most of the state while requiring it to open a pilot program in two counties, Friesen said the attorneys’ proposal is problematic.

“I am statutorily required to provide these services, and I’ve told General Drummond in writing and verbally multiple times that I will not cease any jail-based treatment of any kind across all 77 counties,” Friesen said. “Ideally, if we are going to be forced into this agreement, the pilot program ideally will run parallel to us continuing to provide services across all the other counties in Oklahoma. I will not — will not — cease any kind of treatment of those that are in need.”

But DeMuro said ODMHSAS’ long delays in providing these mental health services “has been a problem for many years” that needs a plan for improvement.

“It’s not just an Oklahoma problem. It’s a nationwide problem that is a smaller part of an epidemic failure to provide mental health services for many parts of the population, and it was exacerbated significantly during COVID,” DeMuro said. “Everything was done in conjunction with the department and the attorney general — his office and his leadership. The attorney general has a vision, I think, for how he wants this to work out, as do we. And he correctly saw early on that the program was broken and violating people’s rights, and instead of wasting time and money fighting it to an inevitable conclusion, we very quickly got into a collaborative mode with the Attorney General’s Office and the department to come up with the state-of-the-art program we have.”

Despite DeMuro’s statements, Friesen said she is unconvinced of the proposal filed Monday.

“I’m not confident in the specifics of consent decree in its entirety. A lot of these specific ‘solutions’ or ‘potential solutions’ are valuable and good standard practice. However, with this specific problem we are attempting to solve, we don’t know yet what solution is needed. And our team of experts already have solid work plans in place and are trying to understand and get to root causes of the problem. (…) I know I’ve said that multiple times, but it’s because that’s what we have to do here. So when we talk about who’s sitting in the physical jail setting, and then who’s transferring to OFC, that should be our clinical experts that are making that determination and developing that kind of algorithm to determine who truly needs an inpatient setting and who can be restored in the jail-based setting.”