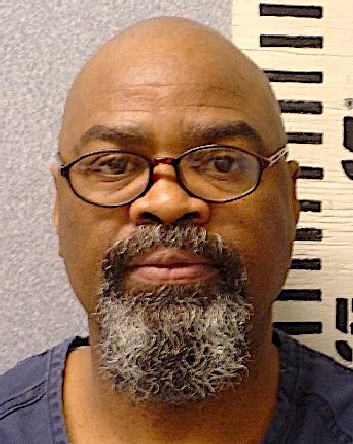

The state of Oklahoma has agreed to pay the maximum amount allowed by law to settle a tort claim filed by a man who spent nearly a half century in prison for a 1974 murder he did not commit. A judge in December found Glynn Simmons to be “actually innocent,” making him the longest-serving inmate to be declared innocent of a crime.

Oklahoma County District Court Judge Shelia Stinson issued an order June 20 approving the Glynn Simmons settlement, which requires the state to pay him $175,000 and means Simmons, 70, will receive the equivalent of $3,646 per year of his wrongful incarceration.

Put another way, the settlement equates to less than $10 per day for his more than 48 years behind bars.

On June 12, Assistant Attorney General Julie Jones Corley filed an application for the settlement to be approved under the Oklahoma Governmental Tort Claims Act.

“This settlement and compromise, in complete satisfaction of any and all demands by the claimant resulting from his claim against the state of Oklahoma, and without admission of liability, is in the best interest of the state of Oklahoma and should be approved by the district court and entered as a judgment as provided by law,” Corley wrote.

Phil Bacharach, communications director for Attorney General Gentner Drummond, said his office had no comment on the Glynn Simmons settlement.

‘He had nothing to do with it’

Initially sentenced to death, Simmons had maintained his innocence all along, repeating details he revisited in a broad interview Wednesday at his new home in northeast Oklahoma City.

Atop his list of exculpatory factors stood a primary problem with the state’s case against him: When Carolyn Sue Rogers was murdered inside an Edmond liquor store on Dec. 30, 1974, Simmons said he was living in Louisiana.

Nonetheless, he and co-defendant Don Roberts were convicted for the murder in 1975. Their death sentences were reduced to life in prison in 1977 after the U.S. Supreme Court issued Oklahoma-related rulings on capital punishment. Roberts was released on parole in 2008.

Attempting to enjoy his reclaimed freedom while processing the decades lost behind bars, Simmons told his story from the couch of his new OKC home Wednesday. Over the past year, he has engaged a “wraparound support system” to develop a food truck concept set to launch this month. Once that becomes sustainable, he has dreams of establishing a nonprofit to support people in similar situations.

Asked his thoughts about the $175,000 settlement, however, the smile on Simmons’ face disappeared. From a couch in the living room of his tidy new home, Simmons drew a deep breath took a serious tone.

“I think it’s bullshit,” he said. “Now, don’t get me wrong, the attitude of gratitude is always with me. But I’m going to call it like I see it. They paid private prisons more to keep me in the cell than they agreed to give me on this $175,000. That’s less than $3,600 a year.”

While he said the $175,000 will help him launch the food truck and meet other needs, Simmons said the restitution does not equal the severity of the state’s mistake.

“It’s a mockery. I’m not ungrateful for it, and I sure need it,” he said. “But when you do the math — and mathematics is the only language that’s pure — you can change everything up, but if one and one ain’t two, it ain’t right.”

For the last 22 years of his incarceration, Simmons said the Oklahoma Department of Corrections paid about $48 a day per inmate to the GEO Group to house him at the Lawton Correctional Center, a private prison whose operations and financial claims have drawn scrutiny. By comparison, the $175,000 settlement amounts to paying Simmons less than one-fourth of the $48 per diem rate Oklahoma pays to the private prison.

Simmons said he would like to see the $175,000 cap removed in the Oklahoma Governmental Tort Claims Act, arguing that jurors should be allowed to hear evidence and set damages.

“Here’s an alternative: Keep your money and hold those accountable for who done it,” he said.

Simmons said he spent exactly 48 years, five months and 18 days in prison before being released in July after prosecutors agreed key evidence in his case had not been turned over to his defense lawyers. Ruled innocent in December, Simmons became the longest-imprisoned U.S. inmate to be exonerated, according to data kept by The National Registry of Exonerations.

One year later, Simmons has a living room illuminated by sunlight and a plant that seems well loved. His back yard and neighborhood seem almost surreal.

“I’ll be out in the backyard walking in the rain, you know? I’m enjoying every bit of this,” Simmons said. “People think I’m kooky, but I ain’t. I’m just into nature and stuff, you know? Yeah, God is good. That’s all I know, God is good.”

Tulsa attorney Joseph Norwood, who has represented Simmons through his release process and tort claim settlement, said his client never should have been charged.

“The state of Oklahoma has agreed to pay the max because clearly he is innocent — clearly a judge found him innocent by hearing convincing evidence, and he had nothing to do with it,” Norwood said. “And the state, instead of litigating a case that they would highly likely lose, decided to go ahead and pay him the max.”

Norwood filed the tort claim for wrongful conviction and incarceration in January with the Office of Management and Enterprise Services. He also said Simmons was in Harvey, Louisiana, where he was born and raised, at the time of the Edmond robbery and murder.

Simmons moved in January 1975 to Oklahoma, Norwood said, and he ended up being arrested, charged and convicted of the murder/robbery “despite not being in the state when the murder occurred.”

Simmons, who had moved to Oklahoma to look for work, had no previous criminal record. When he was a juvenile, Simmons said he was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct for marching in a protest against the Vietnam War.

In the Edmond murder case, the only piece of evidence against Simmons was his identification by a customer who walked into the liquor store in the middle of the robbery, saw the perpetrators for a few seconds, and was then shot in the back of her head, Norwood wrote in the tort claim. The woman testified in court that she had picked Simmons and Roberts out of a lineup.

But about 20 years later, Simmons hired a private investigator who requested the case file from the City of Edmond.

“When the file was received by the private investigator and Simmons, it contained a police lineup report that was not turned over to Simmons at the time of the jury trial,” Norwood wrote in the tort claim. “That lineup report showed definitely that the eyewitness that testified she identified Simmons in a lineup never did identify Simmons, she identified two other people.

“This lineup report that was not disclosed to Simmons at his jury trial, the lineup that was conducted and the totality of the case and trial against Simmons violated his rights.”

Over the years, Simmons said more people came to believe he was innocent. Robert Mildfelt, the assistant Oklahoma County district attorney who prosecuted Simmons, wrote letters to the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board on Simmons’ behalf. Underscoring a phenomenon highlighted recently by 60 Minutes, Simmons also had letters sent on his behalf by the sister of the murder victim.

“We became friends, and she started supporting me,” Simmons said.

In April 2023, Oklahoma County District Attorney Vicki Behenna — a former director of the Oklahoma Innocence Project — requested that the court vacate Simmons’ judgment and sentence after uncovering evidence that could have benefited him. The evidence was found while preparing for an evidentiary hearing.

Simmons was released from prison on bond in July after Oklahoma County District Court Judge Amy Palumbo granted Behenna’s request to dismiss the case. Palumbo later that month vacated Simmons’ sentence “in the interest of justice.”

Federal lawsuit against Edmond, OKC set for March trial

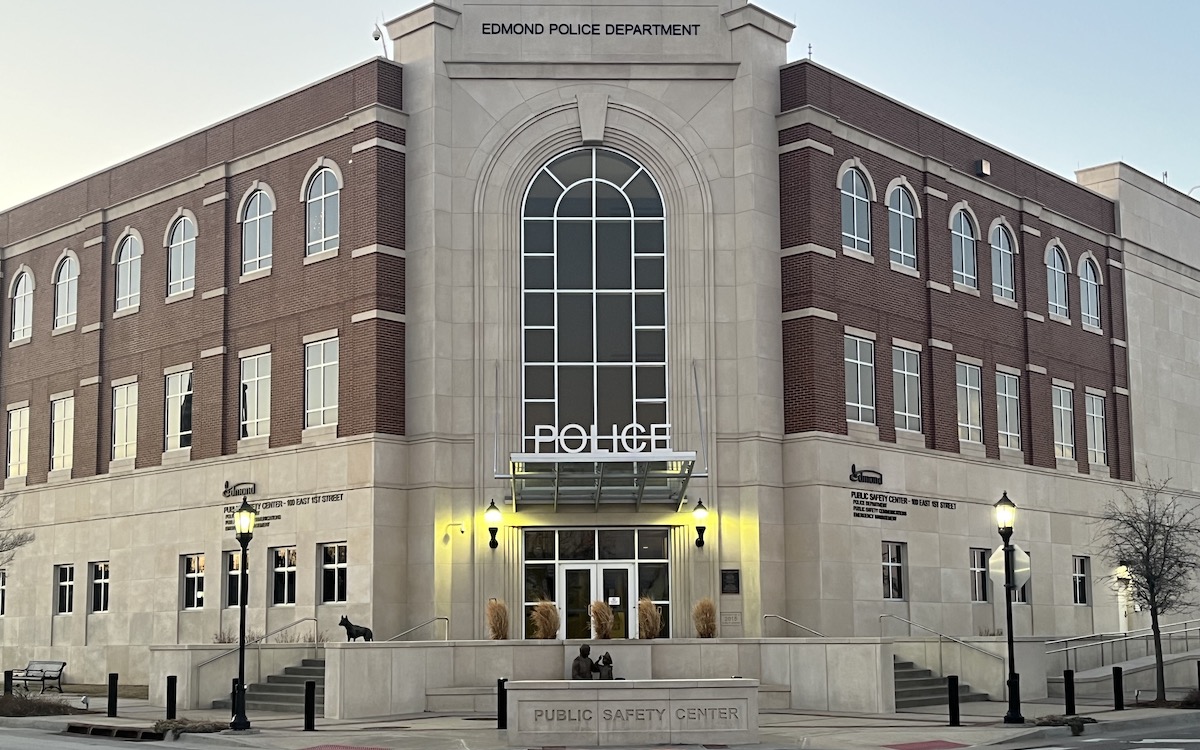

In January, Simmons also filed a federal lawsuit against the City of Oklahoma City, the City of Edmond and two law enforcement officers involved in Simmons’ arrest and conviction. His petition (embedded below) alleges that the detectives — Claude Shobert and the late Anthony David Garrett — fabricated police reports claiming the witness had identified Simmons and Roberts.

“These exculpatory police reports were knowingly and deliberately suppressed by the defendants in order to frame plaintiff for a crime he did not commit,” the petition alleges. “The constitutional violations complained of by plaintiff were a highly predictable consequence of a failure to equip Edmond and Oklahoma City police officers with the specific tools — including policies, training and supervision — to handle the recurring situations of how to handle, preserve and disclose exculpatory evidence; how to conduct proper identification procedures, including lineups; and how to write police reports and notes of witness statements.”

By serving the majority of his life in prison, Simmons was wrongfully deprived of his entire young and middle adulthood, the lawsuit states.

“He must now attempt to make a life for himself outside of prison without the benefit of the decades of life experiences which ordinarily equip adults for that task,” the petition states. “The emotional pain and suffering caused by losing 49 years of life to prison has been enormous. (…) For example, as a result of his decades in prison, plaintiff lost his chance to raise his son, who was only 3 years old when plaintiff was arrested and taken from his family.”

Norwood said a jury trial is scheduled in March, but a judge has ordered the parties to go to mediation.

On Monday night, the Edmond City Council met for about 40 minutes in executive session to discuss Simmons’ lawsuit. After returning to open session, Mayor Darrell Davis announced that “no action” was taken during the executive session.

‘I kept struggling, and I kept surviving’

In an interview Wednesday morning at his new OKC home, Simmons said he got through nearly a half century behind bars by knowing he was innocent. But being innocent worked against him, he said, because Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board members saw inmates admitting guilt as the first step to be considered for release.

Simmons calls it the burden of innocence and the luxury of guilt. He said he stopped asking to appear before the Pardon and Parole Board in 2014 after a 2-2 vote on his request for parole. The board was without a fifth member — another criticism of state law that has been suggested for revision — and the 2-2 vote was considered a denial.

“For 30 years, I went up there seeking mercy,” Simmons said. “I wasn’t seeking no justice to right the wrong. All I was doing was seeking mercy.”

Simmons said faith played a large part in coping with the knowledge of his own innocence, but he said few would listen to him for a long time.

‘I had faith, but holding faith is two different things,” he said. “You know, sometimes you lose it and you got to get it back the same way with patience. You’ve got to be able to hold it. Yeah, I had a lot of faith, and I lost faith many times, you know, the same as the sinner who fell only to get back up.”

Simmons said he had “a lot of family and friends’ support,” which combined with his innocence, “motivated me to keep trying.”

“A long time ago, my mom told me, ‘Every day above ground is a good day because you’ve got a chance to get it right, and you’ve got a chance to make it right,'” Simmons recalled. “So, I kept struggling, and I kept striving.”

About a year before his release in July, Simmons said he experienced an anxiety attack. Then, he started hearing the words that Jesus Christ told his disciples.

“He said, ‘Why marvel at the things’ — talking to all his little disciples and stuff — ‘Why marvel at the things I do when you can do even greater?'” Simmons explained. “Now, he didn’t say the blacks or the whites or the rich or the poor or the Christians or the Jews or the Muslims. He said, ‘You.’ And he was talking directly to me, you know? That’s how I took it.”

Simmons said he interpreted the message to mean there is no instant healing. Instead, healing becomes a process.

“I figured out the manifestation,” he said. “That’s how I got out of prison — the manifestation of my liberation. It starts with belief. I’m talking about that kind of belief that nobody could shake. Nobody could get nothing in between that belief. And that belief, when you get it right, it morphs into a fate, like that caterpillar and that butterfly. That belief morphs into a fate.”

Simmons said he came to believe he would soon be free.

“I’m walking around, ‘My name is Glynn Simmons. I’m a free man.’ Eight, nine months before I got out. I’m speaking it,” he said. “Every step of the way. After you start speaking, you start acting it.”

‘I was young and radical and mad’

Simmons had visualized leaving prison before.

After his conviction in 1975, Simmons said he was angry about being incarcerated for a crime he didn’t commit. Early during his imprisonment, Simmons said he received 30 “write-ups” for insubordination and being disrespectful.

“You know, I was young and radical and mad,” he said.

Simmons said he made filings trying to present his case. Eventually, he thought his case would be reviewed and he would be found innocent. After 10 years went by without justice, he had experienced enough.

The Department of Corrections eventually moved him to the John Lilley Correctional Center in Boley, a minimum-security facility.

“I could hear just the sound of my head, ‘Here’s your chance,'” he recalled. “I’m gonna take it or leave it.”

After three days, he said he and another inmate escaped. They made it to New Orleans and then headed west across Texas to New Mexico. They were stopped about a week later near Las Cruces, New Mexico.

“By that time, I guess, Interstate 10 had become a drug corridor,” he said. “My partner, who was driving, he jumped out of the car and ran.”

Simmons said he was not paying attention and thought they were slowing down to pull over at a rest stop. He stayed in the car, which was surrounded by armed officers.

Simmons said he was returned to Oklahoma, and he defended himself during his escape trial.

“My argument was that the life sentence was illegal, so the escape was legal. It was legit,” he said.

Simmons lost his argument and received a five-year sentence on top of his life sentence.

After Simmons was found actually innocent in December, it was discovered that he still had the escape conviction. That case was dismissed about a month ago, he said.

Glynn Simmons launching Free Man’s Food Truck

With both convictions officially off of his record, Simmons is trying to get on with his life as he approaches the one-year anniversary of being released from prison. A Stage 4 liver cancer diagnosis has left him with another battle to fight, but he insists you will hear “no complaints from me whatsoever.”

“I have more good days than bad days, so I’m doing good,” he said. “Mainly, I’ve been battling this cancer, this medical treatment and stuff. Mainly that’s what I’ve been focusing on besides trying to get my business off the ground. And I’ve been struggling trying to start my nonprofit. But it’s been beautiful. Being free has been beautiful.”

Simmons said he has undergone chemotherapy and surgery to have part of his liver removed.

“I know I didn’t go through all of this stuff for nothing,” Simmons said. “I knew I was being prepared for something.”

The Rev. Derrick Scobey, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in northeast Oklahoma City, recently sold Simmons a food truck. After weeks of getting the truck inspected and licensed, Simmons hopes to have the food truck operating by the end of the week. If he does, the plan is to serve free food and drinks Friday from his truck, which will be parked at the Church of the Redeemer, 2100 Martin Luther King Ave. Donations will be accepted.

Scobey said he bought the food truck about two years ago with plans to use it to provide meals for the homeless a couple of days a week and to sell meals for profit other times.

“It just didn’t work,” Scobey said. “So, it was better for me to just put the truck up and deal with it at a later time. And then Glynn reached out to me through a mutual friend and said he wanted to take a look at it and possibly purchase it. We met later that day. He looked at it and he said, ‘Yeah, I want it.’ And so, I just worked out a financial agreement where he could go ahead and take it and start his business. And I’ve walked him through all of the paperwork to get all of his licenses and everything.”

Scobey posted a video on his Facebook page this week showing Simmons and the food truck.

Simmons said he is dedicating the food truck to his oldest brother, Donald Simmons. Also called Tag, Donald Simmons was a chef, but he died two weeks after Glynn Simmons got out of prison and before they had a chance to reunite.

Despite being held on bond at the time, Simmons said a judge allowed him to go to New Orleans for his brother’s funeral, which served as a stark realization of just how much time had passed him by.

“I’m meeting family and friends that wasn’t even born when I left,” Simmons said. “And they got grandkids. Yeah, that’s why the reality is — yeah, 50 years. I was shocked. It was definitely a shock.”

Simmons has a picture of his brother painted on the side of the truck, along with a poem he had written:

Good morning beautiful people, a special meal for you today, a plate of love, a bowl of peace, a spoon of hope, a fork of care and a glass of prayer. Enjoy your meal for you are under God’s care. Thank God for Jesus Christ. Amen.

Simmons’ mobile kitchen is labeled “Free Man’s Food Truck,” a name stemming from what a reporter, KFOR’s Ali Meyer, called him when he was released from prison.

“The judge gave the order that I was free, and the sheriffs had to take the shackles off of me and so, uh, I walked out of the courtroom,” Simmons said. “And on my way out, there’s a bunch of reporters, you know, they’re trying to get a story. And I heard somebody in the crowd say, ‘Where are you going, free man?’ And it was Ali Meyer (…) a good friend of mine (who) kept me and my story relevant for 22 years.”

The truck also features an illustration of hands — one holding a wooden spoon and the other holding a spatula — breaking the chains of handcuffs.

“I’m a free man, and that’s why I decided to name the truck,” Simmons said. “I’m free to cook what I want to cook, to serve what I want to serve — my soul food.”

Simmons said he and Andre Armstrong, whom he met in prison in 1979 and became cellmates with several times, often talked about what they would do when they were out of prison. Conversations involved owning a restaurant, which evolved into operating a food truck.

The 66-year-old Armstrong, who was released from prison eight years ago, taught culinary classes in prison. Now, Simmons said, he will be the chef of Free Man’s Food Truck.

Simmons eyes nonprofit based on grace, redemption, salvation

In addition to starting his business, Simmons hopes to establish a nonprofit called Grace Redemption Salvation to help long-term offenders adjust to being free after years of incarceration.

“Our mission is to curtail recidivism,” he said. “A lot of guys come out, and statistics show that, within six to 18 months, they’re back in. I’ve sat there and watched this for years and years. Guys that you would bet would never come back, and for some reason or another they come back.”

Simmons said he has studied reasons for recidivism.

“It’s because they don’t have that wraparound support system within their first six to 18 months to help them react and be back in society,” he said. “And statistics also show that 95 percent of all inmates that get out return to the neighborhood from which they came. So, that’s why they need grace, redemption and salvation from this community at large.”

Simmons, who exited prison with “absolutely nothing,” said he has received that type of support since his release.

“That’s why I was able to walk into this after 48 years and make the adjustment, because I had a wraparound support system, people that were there for me,” he said. “It’s been a tremendous support, charitable donations to help me — food, clothes, shelter, medication, transportation.”

Scobey said he received a call in October about Simmons and how he needed some assistance. As it turned out, his church was having a health fair soon, so he invited Simmons to attend. Scobey’s church often distributes furniture and other items donated by World Vision, so Simmons was able to get furnishings for his house.

“He’s obviously a special person. Like, it’s something different about him,” Scobey said. “He’s not angry, he’s not bitter and all that. So, really, I think he thinks that I have helped him, but honestly, he’s helped me more just to really have a better outlook on some things of life.”

Scobey, who served on the Oklahoma County jail trust before falling short in an April 2023 special election for county clerk, said humans have a tendency to “get jaded.”

“We get cynical,” Scobey said. “And I think I was kind of somewhat maybe on that little path with just some things that had transpired, and he helped me to get out of that.”

Scobey said he is glad Simmons will receive at least some compensation from the state for being wrongfully charged, convicted and imprisoned.

“Well, here’s the thing, there’s no amount of money in the world that could really offset the amount of years that he wasted in prison,” Scobey said. “Nope, no amount of money at all.”

Scobey recalled a statement that Simmons made in November.

“He had gone to Edmond, Oklahoma, and I think Ali Meyer was with him, and he said after that, ‘I did something today I’ve never done before in my life,'” Scobey said. “And they asked him, ‘What?’ He said, ‘I went somewhere today that I’ve never been to in my life.’ They said, ‘Really?’ and he said ‘Yeah.’ They said, ‘Where?’ He said, ‘Edmond, Oklahoma.’

“Never. So that means obviously in 1975 he wasn’t there.”

Read Glynn Simmons’ federal lawsuit petition