(Editor’s note: This article is part of “Fractured,” an examination of the state of American democracy produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit Fractured.News21.com.)

By Christopher Lomahquahu & Eshaan Sarup

WOLF POINT, Mont. — Louise Smith sits at her daughter’s dining room table on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, poring over photographs and newspaper clippings — the everyday scraps that weave a tapestry of her 101 years of life.

She revisits the decades she spent as an Indian Health Service nurse; her retirement to care for her husband, Buck, before he died; and how, late in life, she was named the grand marshal at a parade marking this year’s 100th anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act.

With an umbrella in hand to shield her from rain, she rode the parade route in a convertible clad with a banner that read: “Montana’s Oldest Native American Voter.”

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 took effect nine months after Smith was born, recognizing Native Americans as U.S. citizens and, on paper, extending the privileges of citizenship to them. Yet for decades, states continued to block Indigenous people from voting.

Utah considered anyone living on tribal lands nonresidents and ineligible to vote. Other states, including Arizona, barred people under guardianship from registering to vote and used a court case that likened the relationship between tribal nations and the U.S. to that of “a ward to his guardian” to enforce that ban against Native Americans.

It wasn’t until Smith was in her 40s that the federal government overruled state laws and guaranteed Indigenous people the right to vote by way of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Even now, Smith still casts a ballot every election.

“It’s important,” she says, “because you want to know who you’re voting for or what they’re supposed to do for you after you get them in.

“We all should be voting, you know?”

Today, though, experts warn that some states are once again restricting Native Americans’ access to voting — even as a few, including Nevada, work alongside tribal nations to expand their ability to participate in democracy.

“We’ve consistently been bringing new cases every year,” said Jacqueline De León, a senior staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, which provides legal assistance to the nation’s 574 federally recognized tribes and has brought numerous lawsuits over voting rights violations. “There’s more cases than we have the capacity to cover.”

Those cases include a battle to ensure Native Americans in Thurston County, Nebraska — where more than 50 percent of residents are Indigenous — have an equal shot at representation on the Board of Supervisors.

And one in North Dakota, where lawyers for years have fought state officials over electoral maps that courts say discriminate against Native Americans.

And yet another in Arizona, where the Tohono O’odham Nation and the Gila River Indian Community sued over a law requiring voters registering for federal elections to provide proof of residency using a physical address. A judge last year struck down the requirement after advocates noted homes on tribal land often have no address.

Some experts blame these recent efforts on changes to the federal Voting Rights Act. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a section of the act that forced some counties and states to get clearance before changing election procedures, a mandate intended to protect against discrimination.

Since that ruling, efforts to suppress the vote have increased, said voting rights attorney Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, who directs the Indian Legal Program at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

“Now you can pass all kinds of laws without being precleared,” she said. “There’s been an erosion of voting rights over time … and it’s really up to Congress to do something.”

In 2021, President Joe Biden directed a steering group to study voting barriers Indigenous voters face, and the resulting report included several recommendations for state and federal lawmakers – including a push to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Named for the late congressman and civil rights leader, the bill includes provisions specific to Indigenous voters.

In July, a congressional committee published another report that found Indigenous voters “continue to face persistent and substantial barriers to the right to vote in federal, state and local elections.” Its author, U.S. Rep. Joseph Morelle, D-N.Y., said he hoped a better understanding of the problems would compel Congress to take “strong action” to protect Indigenous voting rights.

Advocates describe the Lewis Voting Rights Act as a revitalization of the landmark 1965 law and argue it would restore needed protections against discriminatory practices that target Native Americans and other voters of color. The bill, however, continues to languish in committee.

Restrictions in Big Sky Country

Some 2,000 miles from the nation’s capital, the Fort Peck Reservation is tucked amid expansive grassy plains and cattle pastures a five-hour drive from Montana’s largest city, Billings.

The Assiniboine and Sioux peoples called this land home for centuries before European settlers arrived. While they once traded bison meat and horses, the tribes now rely on metal fabrication, production sewing and other industrial activities to bolster their economies.

The original inhabitants of Montana left their mark on politics, too. In 1932, Assiniboine woman Dolly Akers became the first Native American elected to the state Legislature. And each year since 1989, at least one American Indian has held a seat in the state House or Senate.

The state is home to about 73,000 Indigenous people, constituting 6.4% of the population, according to census data. Nevertheless, the Republican-controlled Legislature has joined other states in passing restrictive measures that advocates say harm Native American voters.

Dubbed “election security bills” by Republicans, the measures were approved in the wake of unproven allegations of fraud during the 2020 election. One eliminated same-day voter registration; the other did away with third-party ballot collection.

After advocacy group Western Native Voice and tribes including the Blackfeet Nation and the Fort Belknap Indian Community sued, the state Supreme Court in March found the laws unconstitutional, saying they made it “much more difficult … for people living on reservations” to get to a polling place or mail an absentee ballot.

At the time of the ruling, Ronnie Jo Horse, executive director of Western Native Voice, said it reinforced “the principle of equitable access to voting services and the protection of the rights for all voters, especially those residing on reservations where voting barriers are much higher.”

In an interview with News21, Horse said she’d like Montana lawmakers to make an effort to visit Indigenous communities to see firsthand the voting challenges they face.

“I’m hoping that representatives are more open to coming to Native communities to really understand what the environment is and the lengths that we have to travel,” she said. “If we can all come together and discuss things, there’s more that we have in common than (not).”

Despite attacks on their voting rights, leaders on the Fort Peck Reservation are focused on getting people to the polls and encouraging the next generation to get more civically engaged.

Smith recalls taking young voters to the polls to encourage them to get involved in democracy and exercise a right their forebearers fought long and hard to secure.

“My friend and I used to take them in her car. Some don’t have rides,” she said, adding that even today, “I visit all my grandkids … when it’s voting time to ask them if they voted already.”

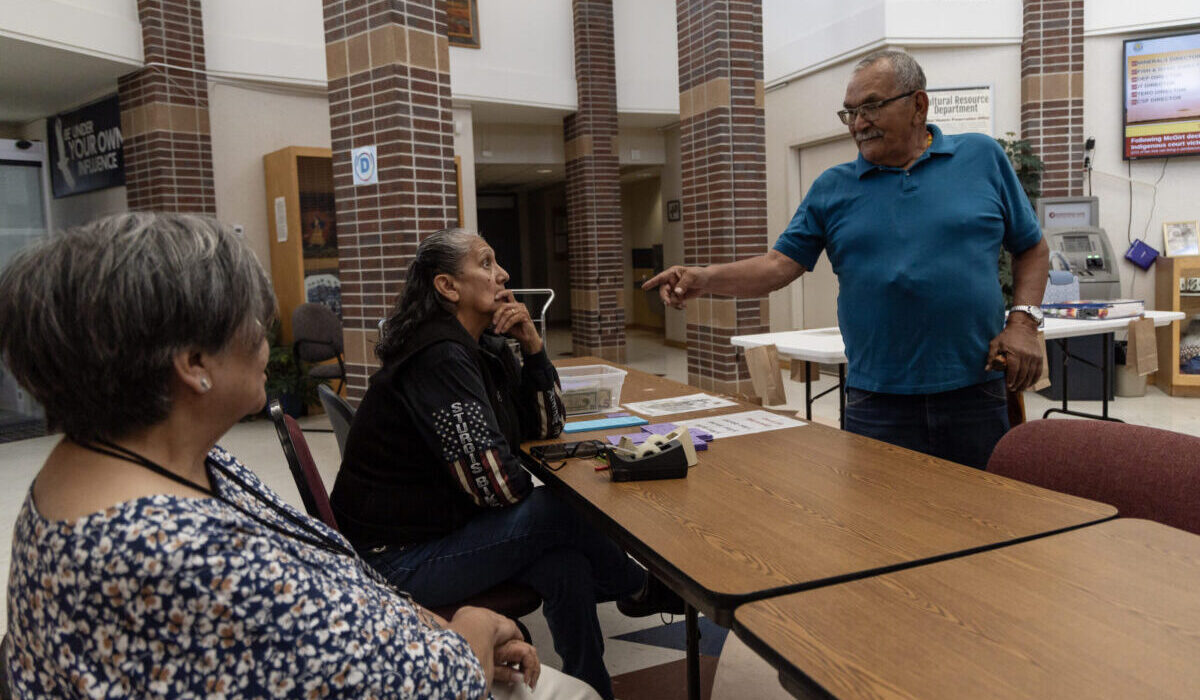

Fort Peck Tribal Executive Board member Wayne Martell has done the same. “You have to go knock on their door, and you have to sit there, and you have to educate them,” he said. “You have to educate them to how the policy personally affects them.”

At 72, Martell has long seen how lawmakers and special interest groups create hardships for Indigenous people. He said voting is about giving his people the power to choose leaders who will make decisions in the best interests of Native Americans.

He points to health care as one example.

After COVID-era Medicaid waivers ended, more than 100,000 Montanans – including more than 12,000 with a tribal affiliation – lost health coverage, according to state data. This November, Montana voters will decide their next governor, along with how the state’s Medicaid situation will be handled.

Other state races, including that of Democratic U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, could be decided by such a small margin that Native American turnout would be the factor. In 2006, Tester won by about 3,500 votes, and campaign officials attributed that — and his re-election in 2012 — to Indigenous voters.

In March, the state Democratic Party launched a multimillion-dollar campaign focused on turning out the Indigenous vote.

“Indian Country is facing tough battles in 2024, and the outcome of this election couldn’t be more important,” Cinda Burd-Ironmaker, the party’s Native vote political director and a member of the Blackfeet Nation, said in a news release announcing the initiative.

“From honoring tribal sovereignty, to improving health care delivery, to combating the missing and murdered Indigenous people crisis,” she added, “we deserve elected officials who will fight for us and be our partner.”

Improving access in the Silver State

In stark contrast to Montana, Nevada’s 28 tribal nations have made great strides toward making voting more accessible for members.

In 2016, members of the Walker River and Pyramid Lake Paiute tribes filed a lawsuit alleging their constitutional rights had been violated because state and county officials failed to establish in-person polling places on their lands – forcing members to travel 70 to 96 miles round trip just to vote.

The tribes won – and soon after, the Inter-Tribal Council of Nevada sought additional satellite polling places for nine additional tribes. Those efforts proved largely successful.

This November, Nevada tribes will have 16 local polling stations – including at the Walker River Paiute tribal courthouse in Schurz and the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribal administration building in Nixon.

“Because of the push from people – not only here on our reservation, but the surrounding Native communities – we’ve been able to create equal voting rights,” said Walker River Chairwoman Andrea Martinez.

That push continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it became essential to provide Nevada’s many rural residents — including Indigenous voters — the ability to vote safely.

A law enacted before the 2020 election ensured all registered voters automatically received a mail-in ballot. It also allowed someone other than the voter to collect and turn in a ballot – a process Republicans call “ballot harvesting” but advocates say helps disabled and elderly people and other voters who lack the means to get to a polling place.

Those provisions helped increase turnout among Native American voters in the state that year by 25% compared with the 2016 election, according to an analysis by the group All Voting is Local Nevada.

In 2021, the state’s Democratic governor signed a measure making those pandemic-era provisions permanent and extending the deadline by which tribes could request a polling place on tribal land.

Then last summer, Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo signed yet another bill, requiring the state to allow Indigenous people living on tribal land to use an electronic system called EASE to register to vote or cast a ballot.

“Nevada has obviously been responsive to a lot of push by tribal communities to make voting easier,” said Steven Wadsworth, chairman of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, located northeast of Reno.

Stacey Montooth, executive director of the Nevada Indian Commission and a citizen of the Walker River Paiute Tribe, said all of these successes are due to leaders in Nevada – and the nation – recognizing the growing power of Native Americans.

Across the U.S., the Native American population grew by almost 12% from 2010 to 2020, according to census data. As for those who identify as Native American in combination with another race or ethnicity, that population nearly doubled.

More than 54,000 people who identify solely as American Indian live in Nevada. That’s about 1.7 percent of the population — enough to make a difference in a tight race.

In 2020, Biden beat then-President Donald Trump in neighboring Arizona by just 10,457 votes, and many credit increased turnout among Native Americans as a key factor. Yet the state’s 22 federally recognized tribes still face unique barriers to voting.

“The demands of each of those groups are very different — and they operate in different spaces, in different places,” said Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes.

For example, election officials use a helicopter to fly equipment to the bottom of the Grand Canyon to ensure the Havasupai Tribe can cast ballots. And some Navajo Nation residents must travel nearly 150 miles round trip to vote.

Fontes acknowledged that in the past, officials sought to intentionally prevent Indigenous people from voting. Now, he said, the main issue is a lack of funding by the state and counties where tribal lands are located.

“They use words like ‘sacred’ when it comes to voting,” he said. “But they don’t want to pay for it.”

In Nevada, Montooth said the growing power of Native Americans and efforts to collaborate more closely with state officials have made a difference — “not just with voting services, but with all the essential services that the state of Nevada provides.”

“We’re at a point now where plans are not made, policies are not implemented, without someone saying: What about the first people of this land?” she said. “Things are definitely improving, but don’t be fooled. We still have a lot of work to do.”

That work includes ongoing battles over voting access.

In the past two years, the voting rights group Four Directions has had to fight for a polling location for Nevada’s Yomba Shoshone Tribe and equal voting access for the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes.

And other barriers remain. For example, a lack of internet connectivity in some Indigenous communities makes the new EASE system impossible for many to access.

One of the biggest obstacles, advocates say, is low engagement among Native American voters — younger ones in particular. A 2020 report by the Native Americans Right Fund found more than 1.5 million eligible Native American voters were not registered.

“It’s not surprising that people don’t see (the electoral process) as something that they want to participate in, because they’re being told in a million different ways that it’s not for them,” said De León, who co-authored that 2020 report.

“We get hit with this label of ‘apathy,’ when in reality what we have is a bunch of compounding difficulties that are telling us the system is not for us,” she said. “All of these combined factors are what make it difficult for Natives to vote and, also, indicate how much power is at stake.”