As classes begin this week at OU, freshman parents around the OKC metro are faced with a choice. Many have sent their students to on-campus housing — where OU reported its first positive case of COVID-19 before classes even began — while others sought and received exemption from the university’s freshman housing requirements.

Jacquelyn Walsh is the mother of an incoming OU freshman and lives in northwest Oklahoma City, near the intersection of Northwest 122nd Street and MacArthur Boulevard. Like many parents, Walsh said her excitement for this milestone in her son’s life has been tempered with anxiety from the ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic.

Thankfully, owing to their proximity to the Norman campus — roughly a 45 minute commute — Walsh would be able to avoid bearing the cost of having her student live on-campus during an uncertain period that has seen numerous other universities ditch their plans to return to in-person instruction after numerous infections.

At least, so she thought. When Walsh learned the details of OU’s freshman housing policies early this summer during a meeting with a university employee, she was surprised.

“I didn’t know about the freshmen housing requirements until we had one of these online Zoom meetings with the money-coach person through OU,” Walsh said. “She was going through everything and made the mention of, ‘Here’s what your housing is going to cost unless you get an exemption,’ and we went, ‘Wait, what?’”

According to OU’s Housing and Food Services website, all freshman students are required to live in on-campus housing “for two semesters.” A list of exemptions exists, including for freshmen age 21 or older, freshmen who are married or have children, and freshmen who already have at least 24 hours of college credit.

The housing policy also exempts freshmen students who “lived in Cleveland or McClain counties during their senior year of high school and will continue living with their parent(s) or guardian(s) in these counties.” But a similar exemption does not exist for students from Oklahoma County or the Oklahoma City area, which can be roughly 30 minutes away from Norman.

“We kind of embarked on this with the idea that he was going to live at home and commute to OU,” Walsh said. “When I saw Cleveland and McClain (on the exemption list), I thought, ‘Why McClain County?’”

Walsh said considering the exceptional circumstances surrounding the upcoming school year, she thought OU had changed its housing policies.

“I just kind of assumed, I guess, that OU had dropped that requirement for this year, and I guess they haven’t,” Walsh said.

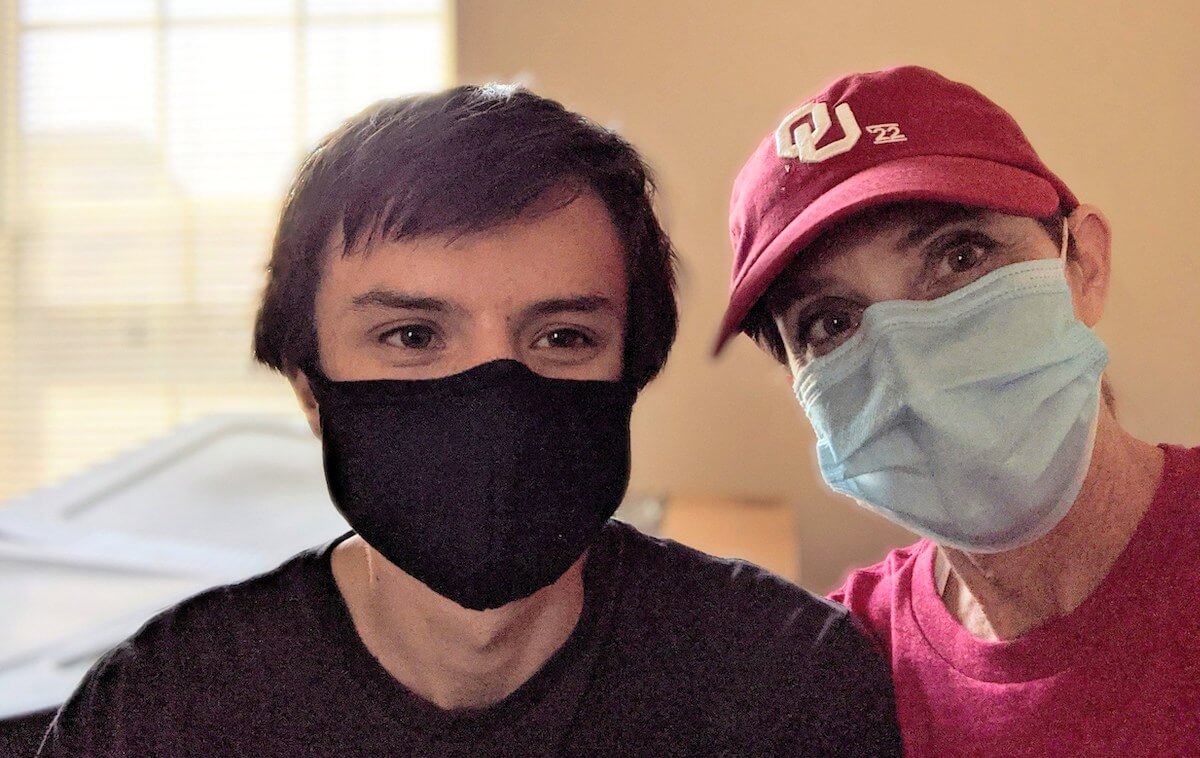

Fortunately, Walsh said she was able to get her student approved for the final exemption listed online: “Students with a verifiable financial, medical, or exceptional need that cannot be otherwise adequately addressed as determined by the UHRC.”

“We kind of made that hard decision to file for the exemption from the housing requirement,” Walsh said. “It’s kind of one of those almost last-minute decisions, but I’m glad that we were able to figure it all out.”

The process of having their exemption approved was swift, Walsh said. She applied for the exemption on a Wednesday, and by the next Monday the university had approved her request. She had questions regarding how seriously the university is reviewing exemptions in the age of COVID-19, however.

“They’re working on it, which is nice, but I’m wondering if there’s not somebody sitting there with a rubber stamp for anybody who’s doing any exemptions,” Walsh said. “That sounds reasonable, just like, ‘Let them go, we don’t want to deal with it.’ It’s gonna be a complete PR nightmare if they start declining exemptions.”

University spokesperson Kesha Keith said OU has granted “approximately 700” housing exemptions for the fall semester, but did not specify if this was higher than average.

Walsh said the only exemption criteria she met was financial hardship. In her letter to the university, Walsh said she noted that she did not want her student to have to take out loans to pay for on-campus housing for what could end up being a stunted school year to begin with, and she also noted the potential additional costs if her student were to contract COVID-19 while on campus and need treatment.

“It was just, ‘Please, have some common sense here and don’t make him live in the dorm if he’s got a perfectly acceptable alternative,’” Walsh said.

Other parents moving their students into OU’s on-campus housing, however, were not concerned. Some said they were confident in the university’s preparations to combat the pandemic.

“I think that OU’s done a great job so far. We’re pretty happy,” said Kenneth Uzick, a Dallas resident who moved his freshman student to campus Aug. 11. “I think they’ve done great in the way that they’ve approached it opening up and having both live and virtual (classes). We’re excited for our freshman and to see how it goes.”

The cost of cancellation

Jennifer Meckling has two sophomore sons, one at OU and the other at Oklahoma State University. She said she understands that for universities, cancelling in-person classes would be a huge blow.

“I feel for the colleges. I understand that it’s a tough situation to be in, and I think they’re facing the same dilemma that my kids face and other parents face in that there has to be some middle ground between mental and emotional health and physical health,” Meckling said. “But I also recognize that we’re in a tough situation, and I honestly don’t know what’s going to happen.”

OU in particular could face a staggering financial shortfall if students do not live on campus, which Walsh said she acknowledged.

“I know it costs a lot of money to not have kids on campus, and honestly I’d like to see the number. I’d like to see the number of kids who get frustrated by this process and don’t end up going (to OU) or choose to stay closer to home,” Walsh said. “It seems like somebody should be doing the cost benefit analysis of losing a student all together for all four years, or losing them to all-virtual (learning) for just one year.”

According to the OU Housing and Food website, the 2020-2021 rate for two semesters of living in a standard double room in one of OU’s three residential towers is $11,324, or $5,662 per semester of the freshman student’s required two-semester period of on-campus living. Other campus housing options are slightly more expensive and slightly less expensive, respectively.

In the fall of 2019, 4,009 freshmen lived in university housing, according to OU’s Institutional Research and Reporting Office. If each of those students remained in on-campus housing for both the fall 2019 and the abbreviated spring 2020 semester to complete their required two semesters of on-campus living, the university would have received roughly $45.4 million from freshman residents.

That figure is before accounting for resident meal plans. For the 2020-2021 academic year, a meal plan will cost students $4,754. If every student who lived on campus in the fall of 2019 and spring of 2020 also paid for a meal plan during that span, another $64.4 million would have been paid by freshmen living on campus. That number does not take into account the food and labor costs associated with meal services.

The figure also does not account for the refunds OU issued to students after classes shifted to online-only following spring break, after which students who were able were given the chance to move out.

OU President Joseph Harroz noted at a July 28 Board of Regents meeting that “about 5,000” students were moving into on-campus housing for the upcoming semester. If students do not live on campus for the upcoming semester, the university could stand to lose tens of millions alongside a projected $25 million decline in athletics revenue, according to the OU Daily.

While Harroz said OU will be pushing to have as many in-person classes as possible, he still acknowledged a fully online semester was a possibility. The university announced its first positive COVID-19 case within campus housing on Aug. 20, before classes even began. Officials said 62 other students had tested positive prior to moving into the residence halls.

OSU faces many of the same potential financial challenges, and the university made national headlines when 23 members of a sorority tested positive. Since then, the university has launched a dashboard for tracking COVID-19 statistics on campus, and OU is expected to launch its own equivalent by the end of the week.

Fall semester ‘comes down to’ students

Meckling said despite the pandemic, she feels it is extremely important for students to be able to learn in person and have a normal college experience for as long as possible.

“I think it’s important for them to be there. And we’re deciding really one week at a time to determine if things continue to be safe for them there, and if it will continue to be safe to pursue that in-person instruction,” Meckling said. “I know the schools are doing the best they can. I think it really comes down to the students’ ability to be compliant with some of those health guidances their ability to be safe themselves.”

At OSU, students have been subject to criticism following the emergence of viral videos which show crowded dance floors and sidewalks in Stillwater.

However, Meckling said there is another aspect to university housing some may not consider: It may be the safest option for students from other countries or those who don’t have a safe home to return to. Her sons are living on campus for a second year to avoid renting off-campus apartments that might have fewer COVID-19 protocols and less flexibility with leases.

“You know, they have sort of a triage system in place at OSU to quarantine students and isolate students, and if it appears to me that that’s not working and there is wide spread, I think the best course of action would be to bring them home,” Meckling said. “But you know, think about that on a campus-wide scale. For some kids, going back to their own homes is challenging, so we have to balance our own needs against the needs of everybody.”

Beyond off-campus concerns, Walsh said simply living in dorm rooms with roommates — an environment which she added already sees many college students getting sick regularly — creates numerous complications as far as who needs to get tested if they’ve had contact with the student, where and for how long a student would quarantine and when the university might consider sending students home.

“It seems like there are some easy ways to mitigate all of that, and that’s just by not being back in person,” Walsh said. “It seems like we’re taking the hard road and spinning our wheels for something that might be a complete disaster anyway.”