Most people don’t consider Tax Increment Financing districts scintillating conversation topics, but there is at least some evidence they can draw a crowd.

About 100 people attended a community meeting April 16 at Oklahoma City University to talk about the proposed creation of a property tax TIF district with city staff, Ward 2 Councilman James Cooper and Ward 6 Councilwoman JoBeth Hamon.

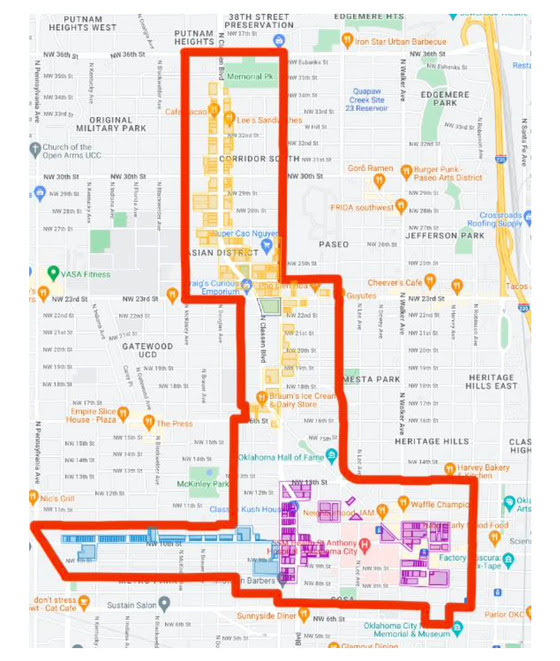

If it’s approved, the proposed TIF district would encompass properties along Classen Boulevard from Northwest 36th Street to Northwest Fifth Street in an effort to spur more development in the Oklahoma City Asian District and areas to the south. The proposed district widens near downtown and would include parts of Pennsylvania Avenue to the west, and Robinson Avenue to the east.

The OKC City Council is expected to begin considering the issue soon, and last week’s meeting offered an initial opportunity for the public to learn about the proposal, ask questions and submit ideas for consideration.

TIF districts offer a slightly complex and sometimes controversial method of creating opportunities for development and redevelopment of areas that need a makeover.

In a nutshell, TIFs can last up to 25 years. When creating a TIF district, cities designate anticipated increases in future sales tax and/or property tax revenues as collateral to borrow money for investment into development, typically in the form of incentives to developers and the construction of public infrastructure like sidewalks and streetscapes.

The loans are ultimately repaid by the increased tax payments from the redeveloped areas.

OKC has a history with TIFs

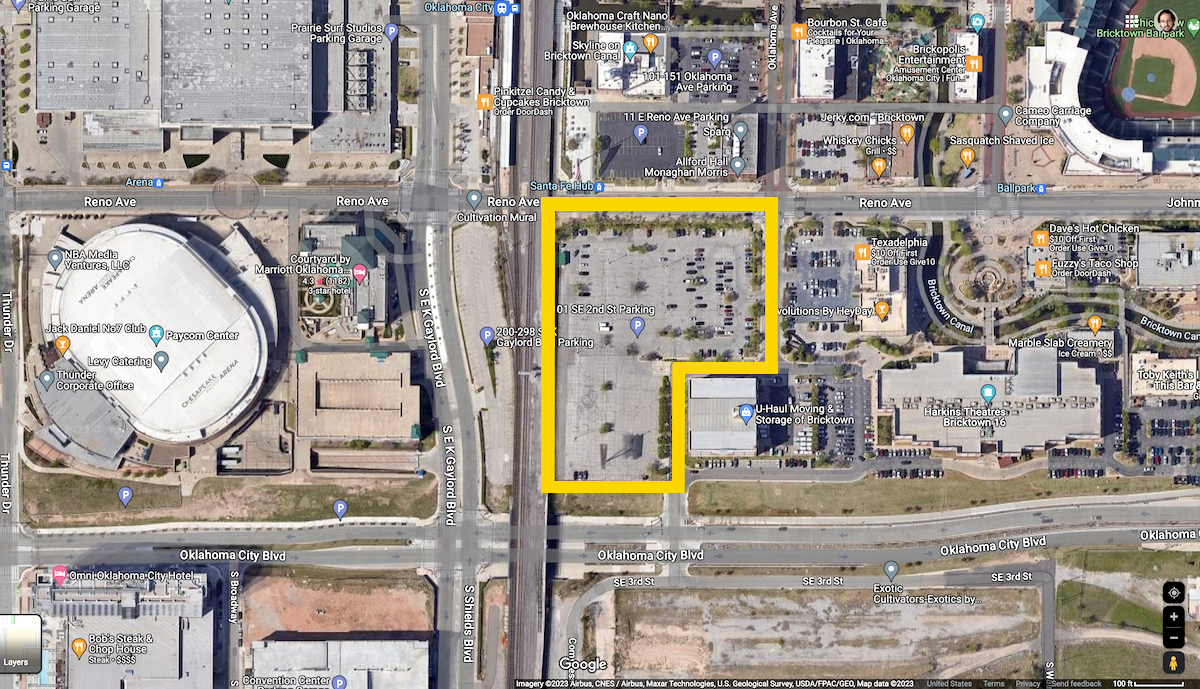

OKC has used TIFs in the past to spur major development projects. The Devon Tower downtown stands as the city’s tallest example. When the property was constructed, part of the project’s funding came from a $115 million TIF. Other examples of TIF-supported projects include the First National Bank building’s makeover and the Innovation District. In September, the OKC City Council approved a TIF district for the massive Boardwalk at Bricktown development, which could receive up to $200 million in property tax rebates and $5.5 million in sales tax revenue. That project has since morphed into a controversial proposal to build what would become the tallest building in the United States.

“For decades now, TIFs have been a valuable tool for revitalizing empty lots and decaying buildings in Oklahoma City,” Mayor David Holt wrote recently in a Facebook post about the proposed North Classen corridor TIF district.

There are about 10,000 active TIF districts in the United States, according to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a Massachusetts-based nonprofit that recommends approaches to economic, social and environmental challenges.

But not everyone is on board with TIFs. Some believe they pick winners and losers in the cities where they are implemented. In some cases, promoting development through TIFs can ultimately be more expensive than traditional financing methods. They can also create competition between schools and municipal governments for tax dollars.

“In the end, it can be a valuable mechanism,” an urban planning and public affairs professor at the University of Illinois told Bloomberg News in a 2018 story about the pros and cons of TIFs. “It’s not something I’d like to get rid of, but it deserves a lot of scrutiny because public sector dollars are being re-routed into a different task, away from general purpose funds.”

In Oklahoma City, Hamon has been skeptical of past TIFs.

“I’m just kind of putting my cards on the table,” Hamon told the audience at the Classen TIF district meeting. “I’m typically very wary of TIF as a development tool. I think like most tools and like most policies, there are unintended consequences.”

Cooper is cautiously supportive of the Classen TIF district proposal, but only to the extent that it would improve the quality of life for those in his ward. In this case, he sees an opportunity for that, particularly if it improves OKC’s affordable housing stock.

Cooper has long been an advocate for creating more walkable, livable urban areas rather than suburban sprawl. He has taken to task previous iterations of OKC city government for what he calls a lack of foresight when it comes to housing by encouraging suburban sprawl.

In his presentation, Cooper recalled the efforts of developer G.A. Nichols, who designed the Paseo Arts District and, across town, the planned community of Nicoma Park where Cooper grew up.

“The way he developed Nicoma Park is the elementary school is right across the street from the church, which is right across the street from the park, and then there is the fire station,” Cooper said. “When Nichols developed the Paseo, which is 100 years ago this decade, he had a very specific vision in mind. Back then, 16th Street was the furthest northern boundary. And so, Nichols had to convince people to move out there. Let that resonate because the work ahead of us is going to require us to revisit the past, to think of how we got to this present moment and move forward into the future.”

To drive his point home, Cooper mentioned the disparity of what’s in OKC’s available housing stock versus the reality of housing demand.

“We have 19,400 Oklahoma Cityans right now who are in need of one- and two-bedroom homes. We only have about 3,600 available units,” Cooper said. “We have built 21,000 three- to five-bedroom homes on the periphery of this city, where people gobbled up farmland by Yukon and Edmond and more. It’s time we make Classen a boulevard again, and it’s time we do so with small businesses mixed in with big businesses and architecture that honors not only the Asian District but honors Putnam Heights, Paseo, Edgemere and Military Park, not these cookie-cutter Chip and Joanna-nonsense things.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Usability, gentrification concerns highlighted in new TIF talks

During the April 16 meeting, Oklahoma City planning director Jeff Butler said the city wants to incorporate usability into new TIF developments like the proposed North Classen corridor.

“When new development happens, as it happens, make it so that it’s more — has a more urban feel,” Butler said. “It’s more functional for the neighborhoods and also addresses the neighborhoods appropriately. So we’re trying to strike that balance between all the good things, connecting neighborhoods, bringing in commercial and employment uses that are desirable, and helping that be done in a sensitive way.”

Saying it would be counterproductive when it comes to creating opportunities for affordable housing, a member of the audience asked about the risks of further gentrification into another area of the city. Butler admitted that is a challenge when creating new TIF districts.

“You do have the risk of increasing property values and having gentrification become a problem. And so that’s something that we monitor on kind of a small scale and larger scales, too,” Butler said. “There’s no easy answer to that. Affordable housing, and subsidized housing, is part of the answer. We’ve got to make sure — and we’re doing an affordable housing implementation plan right now — that’s going to focus on several things that we want to do (and) we have been doing (…). We want to preserve our naturally occurring affordable housing so that we can rehabilitate, preserve those housing units for as long as possible, keep them affordable and keep rents affordable.”

But not every property is suitable for TIF dollars. Butler said those that don’t fit the bill include properties that are declining in value or are unsuitable for other reasons.

“We look at each property to make sure that it’s going to generate some kind of revenue,” he said. “It’s not too risky, because like I said, if you want to have a successful TIF district you need some money. So if you have a property that’s been going down in value or that’s kind of risky for whatever reason, that’s probably not going to be a great candidate to include in a TIF district. If you have a property with a lot of personal property on it, for example, that’s not something you would want to include. There was a recent example of another TIF we were looking at that was just basically an empty site. Not much in the way of building, but it had a ton of personal property. Big trucks and lots of industrial equipment could leave the next day and all that property value would be gone. So we want to avoid things like that.”

Even if a property might be a perfect fit for TIF development, there are other considerations. Joanna McSpadden, the City of OKC’s economic development project manager, said a balance needs to be achieved to get the most out of a TIF district.

“We try to recommend a percentage or an incentive that’s appropriate for the project. We are filling the gap,” she said. “So it’s really analyzing those projects on a case-by-case basis to make sure we’re not utilizing too much of that TIF and we’re not over incentivizing the project, but (we want to) make sure that we can help encourage development.”

‘We are so far behind’

Chelsea Banks attended the TIF meeting because she believes the city needs more affordable housing. She hopes that, if it’s implemented, the North Classen TIF district will help alleviate some of those needs. Banks owns a home but has friends and coworkers who struggle to find affordable housing amid rising rents.

RELATED

As OKC grows, rising costs create housing insecurity by Matt Patterson

“I recognize my own privilege in that I own my home,” Banks said. “But I work with a lot of people who are not in a great circumstance with that. I think when you look at the housing crisis we’re in, it can be very convoluted to understand what that means in practical terms. And that’s sort of what we heard tonight, a percentage of what the actual need is. I understand that there’s data that allows us to have a better sense of what the numbers are and what we need to target, but in this specific instance we know we have a very specific need.”

While encouraged by some of the latest efforts to improve affordable housing stock in OKC, she sees a city that is struggling to catch up.

“We are so far behind,” Banks said. “We have so much work to do. I’m regularly helping my friends find housing. And there are usually several looking at any given time. I’ll be driving by and text them ‘Hey, this property is for rent’. It’s a regular occurrence in my life.”

What constitutes affordable housing

At the April 16 meeting, officials faced other questions related to housing, including what constitutes “affordable” in the city’s mind.

Asked to define affordable housing, Butler said the city uses a formula to determine what is affordable and what’s relative to the area. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development considers affordable housing to be 30 percent of the owner or tenant’s gross income, including utilities. If there is a household with a combined gross income of $6,000 per month, then affordable housing to them is about $2,000 per month.

“It depends on who you ask,” Butler said. “There are different ways of measuring it. If the rent or mortgage is 60 percent or below the median income, that is pretty typical for what is called affordable housing. And there are thresholds after that. The lower you get on the scale — 50 percent and 30 percent for very low-income housing. And of course the lower you get on that scale, the more cost-burdened you are and the more subsidy you would need to have a good quality home to live in.”

Few of the audience questions centered on the commercial development aspect of the proposed North Classen TIF district. Most people asked about housing during the 90-minute session. That fact surprised Hamon, who only briefly mentioned housing as part of the North Classen TIF at the beginning of her presentation.

“I thought there would be a little bit (about housing) just because I sort of primed the pump talking about it at the beginning because it’s always on my mind,” she said. “But I think I really expected people to have questions about the commercial opportunities. But it’s encouraging to hear that this is on the top of people’s minds. Just like, what does this mean for my rent? That’s always a question.”

Hamon said she would like to see more mixed-income developments in OKC’s future housing projects.

“I think that’s really what we don’t do well as a city, because we haven’t figured out what those tools we can be using to incentivize actual mixed income are,” Hamon said. “I think that’s where you have a little bit more stabilization opportunity, both to keep people in place and to increase the number of units. That also affects the market. You don’t want to make it too unaffordable for people already in the area.”

Hamon cited the building she lives in as an example.

“It’s really nice to have seniors who are on a fixed income with young professionals or families or whatever,” she said. “Unfortunately, in a lot of other projects that I’ve seen, the city give incentives of TIFs or other funds in the past. It’s like, it just ends up being young professionals in that housing.”