(Update: One day after the publication of this article, the OKC City Council voted 7-2 to approve the TIF proposal for the Boardwalk at Bricktown project discussed below. With all other council members voting in favor, Ward 2 and Ward 6 members James Cooper and JoBeth Hamon voted in opposition after expressing concern about whether Aspiring Anew Generation can provide the promised housing and workforce services. Ward 8 councilman Mark Stonecipher expressed support for the developer, Matteson Capital, and the project as a whole. The following article remains in its original form.)

As the OKC City Council prepares for a final vote Tuesday on what could become one of Oklahoma City’s largest tax increment financing agreements — a $736 million housing, hotel and retail development — the project’s “financial advisor” says questions about the role of an Arizona nonprofit she helps run are misplaced.

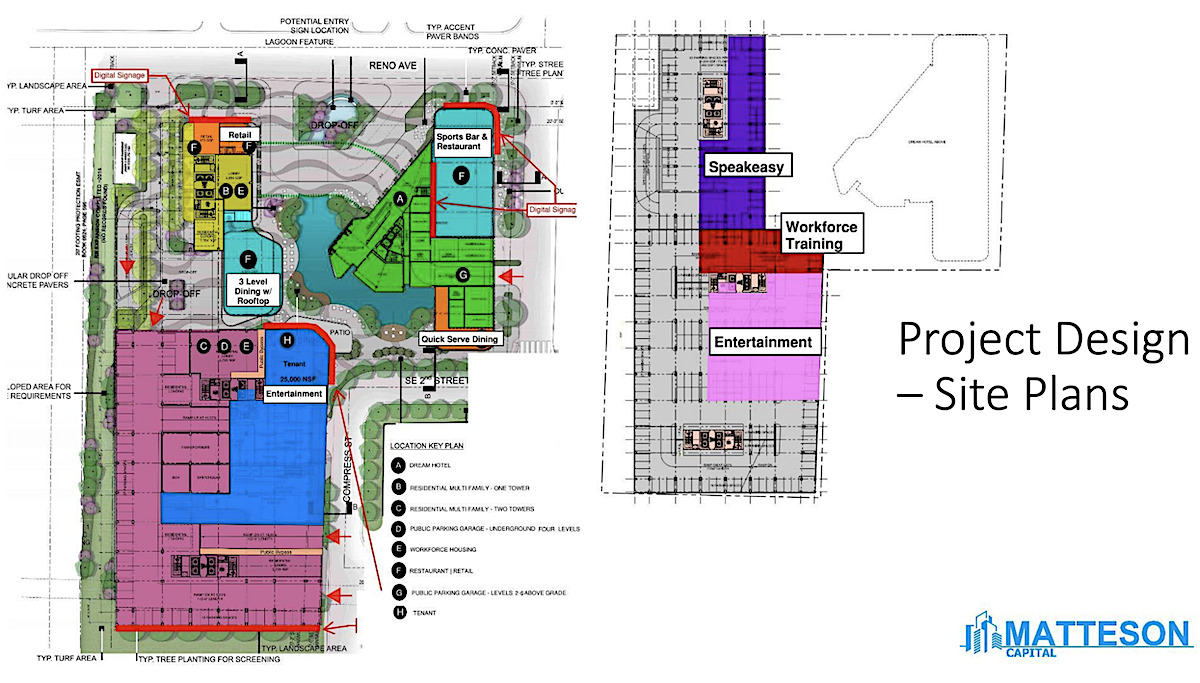

The 25-year TIF proposal offers up to $200 million of property tax rebates and up to $5.5 million in sales tax rebates in support of a three-building Bricktown development that would include retail space, two underground parking garages and 924 residential units, 132 of which would be dedicated for some level of subsidization through a workforce intervention program operated by Aspiring Anew Generation.

A hotel included in the development proposal is ineligible to receive support from the city’s downtown TIF district owing to a prior agreement with the Omni Hotel.

Developed by Matteson Capital, the Boardwalk at Bricktown project is planned southeast of the Reno Avenue and E.K. Gaylord Boulevard intersection, bordered by railroad tracks on the west and a U-Haul storage building to the east.

TIFs have become popular in recent years for cities trying to generate development in certain areas. In this case, city leaders hope the addition of hundreds of rental units to the downtown market could help ease rising housing costs, but questions remain about whether the proposed nonprofit program combined with promises to subsidize 132 units’ rent can mitigate council concerns about the median price of other units in the proposed 27-story and 28-story apartment buildings.

In an interview, city of OKC TIF manager Joanna McSpadden said TIF agreements help fill gaps in financing, with the aim of making a project’s completion more likely and the protection that incentives are not paid unless a project progresses.

“It allows the city to capture future property tax and use that to support and incentivize development and growth,” McSpadden said. “The way that works is a project comes in and they have an estimation of how much they believe their project will generate in increased taxes for whatever the life of the TIF is. This TIF has a 25-year life, depending on what time they enter the TIF. (…) So the city will look at the project and say, ‘OK, where is the gap in the project? Whether that’s a financing gap on the front end or if it’s a gap in operating cash flow in order to make the project happen, what kind of incentive can we provide to help fill in the gap?’ It’s usually some portion of that amount that is generated.”

In the case of the Boardwalk at Bricktown, city leaders are looking for value in its vertical infill of an undeveloped parking lot in downtown OKC. The project proposes three high-rise apartment towers to include “workforce housing,” as well as underground public parking, a Dream Hotel, retail shopping, restaurants and entertainment amenities.

But margins are thin. McSpadden told the OKC City Council on Aug. 1 that the project “will change our skyline and bring new energy to Bricktown,” but she said it is dependent upon the proposed TIF deal.

“The density and verticality, coupled with inflation and higher borrowing costs, are going to make this project incredibly difficult and expensive to accomplish,” she said. “Without substantial help, it won’t happen.”

Kenton Tsoodle, president of the Alliance for Economic Development of Oklahoma City, said the project would become one of the first vertical projects for which the city has allocated TIF funds.

“This one is very significant because we are trying to fix so much development on such a small site,” Tsoodle said in an interview. “If fully developed, it would be squeezing $700 million of development on less than four acres. I think typically we go into things much heavier on things that we feel like are transformative. This is the type of project that we’ve never had before as far as a residential piece in terms of its verticality.”

Arizona nonprofit tied to developer, same-name companies

Proposed within the Boardwalk project are 132 rent-subsidized units. Those units would be managed by Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated, an Arizona nonprofit with connections to Matteson Capital. The organization offers health and housing services, and it operates a clothing bank, childcare programs and workforce programs, according to its website.

“At, Aspiring Anew Generation, we believe that people like plants will thrive in the right soil,” the website states. “Just like a plant that is struggling in one location transplanting it to more suitable conditions will allow the plant to thrive. Helping adults deal with addiction, mental health, homelessness and low income status understand they matter and allowing them to see their full potential (sic)”

In OKC, the organization would manage the rent-subsidized units, operate a workforce training center, offer addiction counseling and provide financial literary assistance to those housed in the units, according to Joanne Carras, a “financial advisor” to Matteson Capital who also serves on the board of Aspiring Anew Generation and as its CFO.

During her presentation to the OKC Council on Aug. 1, Carras referred to Scot Matteson as both the project’s “developer” and as a “philanthropic partner” for Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated. She said the proposal’s benchmark of $1,800 per month for the 132 subsidized Boardwalk apartments is based on federal housing data and is higher than the rates likely to be offered to those entering the nonprofit’s program.

“I’ve been [Matteson’s] financial advisor on this project, but somewhere in the process — because we’ve been working together for years — I became an officer of this nonprofit, another passion of mine,” Carras said. “It’s not often where you see this inclusivity where you’re helping people. The rent could be zero (for the subsidized units). But we’ve agreed — again, no obligation, but we’re voluntary agreeing, and I know our funding is going to trigger the rent — we will not exceed the HUD low-to-moderate-income AMI.”

Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated is only a proposed tenant within the Boardwalk project and would not receive TIF funds from the city, McSpadden said. The TIF agreement is not contingent on AAG’s participation, she said.

Still, the proposal for AAG to operate workforce programs and administer rent subsidies for people trying to transition from the streets into housing has helped mitigate concerns about what otherwise will be expensive apartments, Ward 2 Councilman James Cooper said Aug. 1.

“Your workforce approach makes me more comfortable because I was not comfortable with the market-rate stuff (…) separate from the workforce,” Cooper said. “That was giving me a lot of heartburn and some of my residents heartburn. But this is a very thoughtful way to mitigate that.”

Carras told council members that the Boardwalk project will be built tower by tower based on leasing benchmarks and that it will take between two and six years for completion.

The Aspiring Anew Generation nonprofit, meanwhile, appears to be in its early stages, and questions about its capacity and status in Arizona have spurred private conversations among OKC nonprofit leaders who say the tall task at hand will not be easy for a nascent nonprofit.

At the Aug. 1 meeting, Ward 6 Councilwoman JoBeth Hamon asked Carras which OKC social service organizations her team has met with as they plan for their nonprofit housing and workforce project in the Boardwalk.

“We started with the day shelter, even though we’re not a shelter. We don’t function on a daily basis. We are a program that the client or individual that has issues retaining jobs or a career, they volunteer, but they sign up, and it’s a regimented program for two years,” Carras said. “Everybody is individually assessed. So it could be a mental illness, it could be a traumatic event, they could have lost a spouse. It could be domestic violence, and now trying to get away — need to get a job. So we’re helping the people that have many reasons why they are having hard times sustaining employment. (…) It’s all about getting back on their feet.”

Carras said other outreach efforts to potential community partners would be ongoing.

“We also collaborate with other areas like seniors, veterans, the Native American tribes,” she said. “We do provide service to those groups.”

For those who have tried to learn more about Aspiring Anew Generation, no physical address or telephone number is posted on the entity’s website. The site does not list an executive director or a board of directors. The organization does not maintain a Guidestar page, but it appears in the IRS database of tax-exempt organizations as “Aspiringanewgenerationincorporated.”

Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated registered as a nonprofit corporation with the Arizona Corporation Commission on June 30, 2021, and it was approved for 501(c)(3) status in August 2022. It is connected to and has the same registered agent as a pair of for-profit corporations called AAG Family Corp and Aspiring Anew Generation Clinic LLC, which were registered Nov. 18 and Nov. 22, 2022, respectively.

Last month, The Mesa Tribune in Arizona reported that, on June 23, Aspiring Anew Generation Clinic LLC became one of dozens of entities whose Medicaid provider participation has been suspended “in the wake of a crackdown on fraudulent Medicaid billing announced by Gov. Katie Hobbs and state Attorney General Kris Mayes in May.”

However, Carras told NonDoc by email that the for-profit side of the organization’s Medicaid billing was suspended — like numerous other providers — only because of staffing shortages within the state of Arizona’s Medicaid compliance department.

“All the licensed clinics involved with this program in AZ have been temporarily put in a no billing status because the state was lacking oversight and staff,” Carras wrote. “So they had to stop billing for all licensed clinics until they meet with each one to ensure they understand the new guidelines issued by the state. The licenses are not suspended and the clinics are not closed.”

Carras, whose email signature lists her as “CFO” and a “board member” of Aspire Anew Generation, said the Mesa newspaper story was inaccurate.

“The article has commingled that unrelated fraud situation with the clinics that are in the audit phase to ensure that the state can review all clinics’ new billing requirements,” Carras wrote. “It is very complex, but again, as I said, none of this has anything to do with the nonprofit.”

NonDoc asked Carras for a copy of the organization’s most recent Form 990 IRS filing — which 501(c)(3) organizations are required to make available for public inspection — but no 990 was provided prior to the publication of this article.

McSpadden said her office within the city of OKC does not have Form 990 from Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated.

Meanwhile, Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated has a status of “pending inactive” on the Arizona Corporation Commission website, which states that the organization did not file a required annual report by a June 30 due date this summer. The site notes that the organization did file its report in 2022.

A former member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and a former assistant deputy mayor for the city of Los Angeles, Carras is listed as the executive vice president of BCREM Capital based in Calabasas, California.

BCREM, which stands for Better Commercial Real Estate Mortgages, offers a variety of commercial real estate development services, and Carras “oversees the firm’s public & private advisory development incentives,” according to her bio.

In her emails to NonDoc, Carras said Aspiring Anew Generation’s “legal team is geared up to pursue any organization that causes more damage or defames the nonprofit.”

“A professional journalist that seeks the truth will figure this out. You have to do your homework and not copy another persons lazy story,” Carras wrote. “Several of your colleagues have drilled down and figured it out. That’s why you see no follow up to a baseless story. While we appreciate your reaching out to ask questions, so did your colleagues. They confirmed the truth and as such, there is no story. It’s simple bad journalism and your colleagues were shocked giving us advice on how to go after the Mesa Tribune.

“The article from Mesa is a hit piece by NIMBYS trying to eliminate permanent supportive housing for people in need.”

Challenges could be faced by Aspiring Anew Generation

According to Carras, Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated was founded by Jessica Stanford, who has experienced challenges related to housing and is “an inspiration to everyone she helps.” While her online presence is limited, Stanford is noted as having a Ph.D on the AAG website.

“Our vision, Aspiring Anew Generation is a community is an initiative that is driven on providing sustainable resources to youth and families,” reads a quote attributed to Stanford on the site. “In our efforts to ensure that our generation’s knowledge, wisdom and resources are embedded in future generations to come.”

The nonprofit plans to provide “wraparound services” for the people who move into the Boardwalk at Bricktown’s 132 subsidized units, according to Carras. Those services include a workforce development center and financial and addiction counseling.

“You will see, we’ve provided a lot of benefits out of our voluntary willfulness to be part of your community and make sure everybody feels we’re coming in offering you really great economic benefits,” Carras told the OKC City Council on Aug. 1.

The organization will work with those who may have experienced homelessness in the recent past or who are one financial hardship away from facing it again, she said.

“We’re looking to help people get back on their feet for whatever issue they have where they were unable to sustain a job,” Carras told council members. “The benefit here, because our program is a two-year program — usually people graduate and then they would exit the housing so we can have other people come in and benefit from the programs we’re offering, even though we monitor them off-site — that will translate to 7,000 people getting reemployed, possibly becoming entrepreneurs and creating more jobs, so that is an exciting number for us for the community.”

Homeless Alliance executive director Dan Straughan said the Boardwalk at Bricktown’s proposal for serving the unhoused or those facing housing insecurity raises a lot of important questions.

“When the proposal was first brought to my attention (…) the proposers were saying that they work with chronically homeless individuals and that the clients would be employed and self-sustaining within 12 to 24 months,” he said. “In my experience, that’s possible for some chronically homeless individuals, but not many. My understanding is they backed off working with the chronic population and will target a less-challenging demographic.”

Straughan said wraparound services intend to break down multiple barriers that are commonly found by those who are unhoused.

“One of the hallmarks of homelessness generally — and chronic homelessness, in particular — is that the individual or family generally has multiple barriers to stable housing,” Straughan said. “Things like lack of access to transportation, mental illness, lack of educational attainment, substance use, unpaid fees, and fines, a criminal record, very low income, illiteracy, physical disability, lack of access to primary medical care.”

Straughan said it can be nearly impossible for one agency to provide complete wraparound services.

“There is no single agency or entity that can address all those issues and navigate the system of multiple government, faith-based, and nonprofit agencies that work in those areas, each with their own target demographic, eligibility requirements, paperwork,” Straughan said by email. “The mission can be daunting — especially for someone who has one or more of the barriers I just listed. Wraparound services lift that burden off the homeless person and places it on their case manager, who is typically a social worker (or peer support person) and has experience navigating the system on behalf of their client.”

Oklahoma City’s homeless population is about 1,436, according to the city’s most recent annual count. But that total does not include those on the margins who could become homeless at any time.

Straughan said the challenges to providing “wraparound services” are numerous. Caseworkers make about $30,000 to $40,000 annually in OKC. If Aspiring Anew Generation were to take on more than 100 clients, at least five full-time caseworkers would be needed to work with those living in the 132 subsidized units, he said.

Competition to hire case workers and social workers is stiff, Straughan said. OKC already has established nonprofit organizations like the Homeless Alliance, TEEM, City Care, the Mental Heath Association of Oklahoma, City Rescue Mission, NorthCare and others that provide some of the same services discussed by Carras and Aspiring Anew Generation.

“Why would you bring in an out-of-state entity to do that?” Straughan said. “Especially one with a questionable background. (It) boggles the mind.”

Straughan said he wonders how an out-of-state organization would be better suited for that work than those already active in the city, although he believes everyone involved should work together.

“Oklahoma City is so short of housing that any entity that seeks to add to our housing stock, we’re going to try to find a way to work with productively,” he said.

Rent affordability remains an issue

Asked about the pending TIF proposal, Hamon said one of her questions about the Boardwalk project, and other developments that receive TIF funding, is whether developers will actually deliver on what they promise.

In this instance, the development team’s description of how the Arizona nonprofit would provide services and subsidized housing appears key to the overall proposal, even if the TIF funding is not dependent on that work.

“The thing that concerns me is there is nothing in the TIF agreement that holds them to that,” Hamon said. “If the developer decided to cut those things out of the model, they have the ability to do that with no repercussions on their TIF allocation. It’s nice they are proposing it out of the goodness of their hearts and that they think it’s doable, but (…) projects that were touting themselves [as] ‘workforce affordable’ a few years ago are saying, ‘Sorry, we can’t do that anymore,’ and there’s nothing keeping them from that. But they still have access to these public subsidies. The investors aren’t suffering. They’re not having a need that is not met. The city is having a need not met.”

When it comes to the subsidized housing, workforce development and life skills counseling portions of the proposed Boardwalk project, Hamon said Aspiring Anew Generation’s presentation to the OKC City Council on Aug. 1 did little to assuage those concerns.

“What they presented at the council doesn’t provide me with a lot of confidence that they can successfully do this without a lot of help and support locally, which is fine, and why I wanted to connect them to local organizations so that they can collaborate,” she said.

Cooper, the Ward 2 councilman, said OKC’s lack of affordable housing is one of the biggest challenges facing the city today. Rent for the non-subsidized units in the Boardwalk buildings is expected to be in the $2,000 to $2,800 range per month, depending on the size of the unit.

Cooper said downtown rent in virtually every major city in the world is high, which makes it challenging for those without high incomes to afford.

“It might check those boxes, but if a one- or two-bedroom is at a market rate, can our teachers, our police officers — even with the recent raise — afford a $2,000 or $2,800 rent? Can they live there? The answer is no,” he said.

Cooper said he sometimes grapples with how he views TIF agreements. On one hand, they can help fill unused gaps of land in urban cores and reduce suburban sprawl. But on the other, they can have consequences.

“I’ve had a complicated history with TIFs. I think they’re best when we use them to better serve people and not replicate displacement dynamics,” he said. “We need to be asking for more benchmarks than we currently do. Something like an affordability component would make them a lot better than what they have been. I wouldn’t say I’m 100 percent opposed to this one or others, but I always do have concerns about who they benefit.”

Ward 5 Councilman Matt Hinkle said he supports the Boardwalk project, which he said comes at a time when the city is grappling with housing affordability. The first-year city councilman said he sometimes wonders if he could qualify for a mortgage on the home he bought 10 years ago because housing costs have risen so fast in that time.

“If people can’t find affordable housing, they may end up on the street, and that becomes a spiral,” he said in an interview. “There’s a need for affordable housing on all levels. A mom and a dad or a single parent should be able to afford housing and still have the ability to take their kid to the movies if they want to.”

Over the years, Hinkle said, the city’s efforts with TIFs have helped spur development. If fully realized, he said, the Boardwalk project would be among the most important.

“There are a lot of projects that we wouldn’t have had without the TIFs over the years,” Hinkle said. “I think this project is a game changer for the city.”

During the Aug. 1 presentation, Ward 8 Councilman Mark Stonecipher also praised the Boardwalk at Bricktown project. Although he did not mention the nonprofit component, Stonecipher said he had done “due diligence” to review other Matteson Capital developments in California, Colorado and Florida.

“This will energize Bricktown. This is a wonderful thing for the city,” Stonecipher said. “I look forward to working with you all on this, and I hope we have a completion sooner than 2029.”

McSpadden said the city’s TIF agreements are structured to mitigate as much financial risk to the city as possible. The Boardwalk project has been no different, she said.

“I think we have done a pretty good job of creating structures within those agreements that really protect the city’s interests,” she said. “We really try to go into these details to mitigate risk. With Boardwalk, there will be some funding provided throughout construction, but that funding is reimbursement of sales tax paid. That will be all that is funded until they are up, operational and actually leased up to some degree. There are a lot of boxes they have to check before that money starts coming in. From that standpoint, I think we’ve created a system, that while not completely risk-free — because that would be difficult to accomplish, especially with a project this big — we’ve done as much as we can to mitigate as much risk as possible.”

View the Matteson Capital Aug. 1 presentation

Loading...

Loading...

(Correction: This article was updated at 3:48 p.m. Monday, Aug. 14, to state that the city of Oklahoma City did not have a copy of an IRS Form 990 filing from Aspiring Anew Generation Incorporated.)