After using Oklahoma tax dollars to fund a venture in California and allegedly violating a state law that limits how much money a charter school can spend on administrative costs, Epic Charter Schools owes Oklahoma $8.9 million, according to a report from the State Auditor & Inspector’s Office released today.

“What we found was very disappointing,” State Auditor and Inspector Cindy Byrd said during a press conference this afternoon. “I have seen a lot of fraud in my 22 years, and this situation deeply concerns me.”

Embedded below, the Epic audit is being turned over to Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter’s office, the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation and the Oklahoma Tax Commission. Byrd said the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Internal Revenue Service and the Office of Inspector General will also receive the 120-page Epic audit.

For years, the pair of public charter schools have been the subject of a criminal investigation into allegations that include embezzlement, obtaining money by false pretenses and racketeering. The schools have also been accused of enrolling “ghost students” to increase their share of state aid.

“I remain concerned that the money is not getting to the students,” Byrd said. “The lack of cooperation and the roadblocks encountered was unprecedented in the State Audit and Inspector’s Office.”

Byrd said a typical investigative audit might feature two or three subpoenas, but the Epic audit involved “around 50 subpoenas because we were not getting the information we needed.”

“Every taxpayer, every parent has a responsibility to be involved with their public school district,” Byrd said. “It’s time that taxpayers in Oklahoma started using their voice and demanding answers.”

Asked to rank the Epic audit on a scale of one to 10 in terms of her concern, Byrd called it “one of the worst” she had seen in her career.

“I would say this ranks as a 10,” she said.

Background on Epic audit

Byrd was asked to audit the controversial charter schools by Gov. Kevin Stitt in July 2019. Epic has been under criminal investigation for several years owing to allegations of embezzlement and racketeering against the virtual charter schools’ co-founders, Ben Harris and David Chaney.

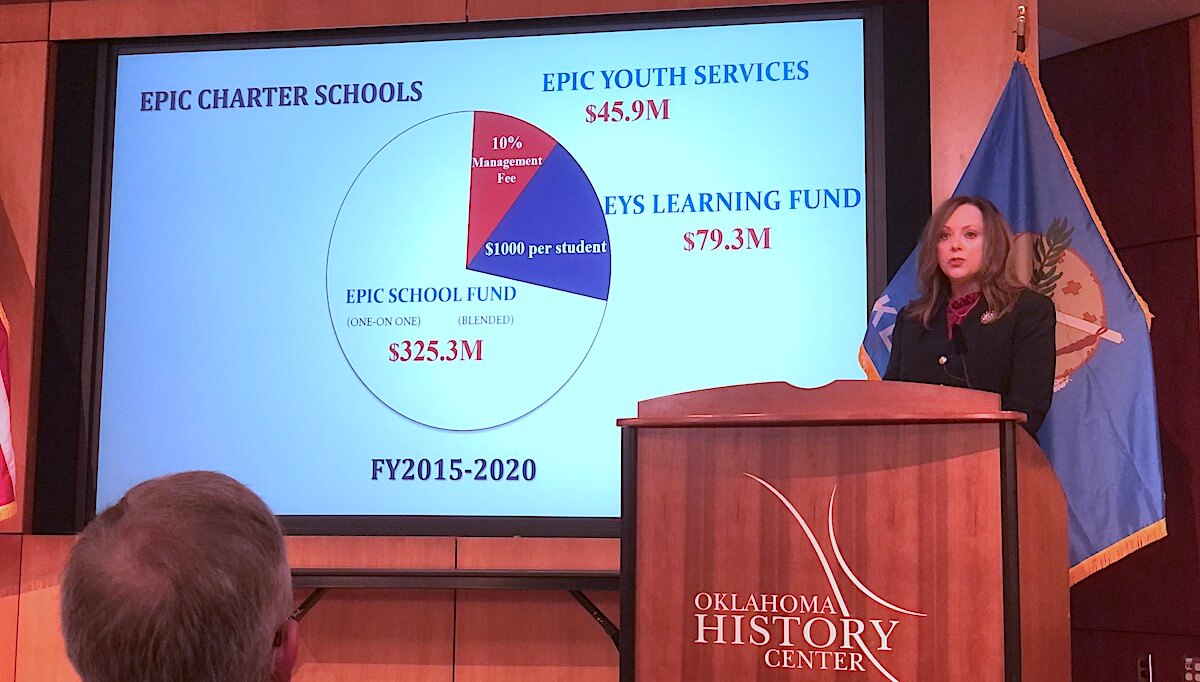

Byrd said Harris spoke with her office for the audit while Chaney refused to. The audit covered the schools’ state allocations from FY 2015 through FY 2020.

Epic offers two school programs — Epic One on One and Epic Blended Learning — that are technically governed by two boards that feature the same membership. Byrd said that “major financial transactions” were made by the schools without board approval.

In March, those board members spent 90 minutes in a late-night executive session and determined that they would not comply with Byrd’s request for documents related to Epic Youth Services, the private management company that the public charter schools use to manage their controversial “learning fund.” EYS receives $0.10 of every $1 in taxpayer money paid to Epic Charter Schools, Byrd said.

In March, the Epic board decided to commission its own audit and fight Byrd’s request in court. The resultant case concerning Epic Youth Services’ financial records is slated for a December trial in Oklahoma County District Court.

As a result, Byrd said Thursday she could not speak specifically about the $46.5 million paid to Epic Youth Services, the $79.3 million in the “learning fund” or the battle for the private company’s financial records.

Administered by Epic Youth Services, Epic’s “learning fund” reimburses student families for up to $1,000 of educational curriculum or extra-curricular purchases. But state investigators have alleged abuse and fraud concerning how the private Epic Youth Services company manages state dollars. In Oklahoma, substantial state funding follows the student, and districts are paid in relation to enrollment.

“We cannot determine if [Epic Youth Services] is entitled to the $80 million they received,” Byrd said. “I would like to leave it at that.”

In recent years, Epic’s enrollment has boomed. Founded in 2011, the charter school announced enrollment numbers in July for the 2020-2021 school year of 40,631 students in 77 Oklahoma counties, making it the largest school district in the state. Epic is authorized by Rose State College to serve students in Oklahoma and Tulsa Counties. The school is also authorized by the Oklahoma Virtual Charter School Board to serve students statewide.

Epic Charter School was founded by Harris and Chaney under the non-profit corporation Community Strategies. However, they are also co-owners of Epic Youth Services, LLC, the private company registered in 2005 to Todd Wedel, a certified public accountant in Oklahoma City.

Epic assistant superintendent responds

Two hours after Byrd’s press conference, Epic Charter Schools assistant superintendent Shelly Hickman released a statement responding to the auditor’s remarks. She called Byrd’s press conference “political theatrics” and said Epic would provide a “point by point response” to the audit within 24 hours.

Hickman’s full statement appears here:

We haven’t had a chance to read this 120-page report. What we witnessed today was political theatrics, but the information was not new and has been in the public realm for many years. What we did witness was Auditor Byrd attacking parents’ rights to choose the public school they think is best for them, and disparaging the work we are doing to provide high quality, remote learning opportunities for over 61,000 students and parents.

We take issue with the auditor’s assertion that we were not helpful or cooperative in this process. Our school’s staff has spent thousands of hours responding to a seemingly endless fishing expedition. We gave them access to our computer system, and to date we have paid $243,000 for the audit.

What the auditor seems to object to is the idea that our school model provides an alternative to traditional public schools. We have grown from only 1700 kids to more than 61,000 students over our 10-year history. Does our Learning Fund help us attract and retain students? Of course it does because it empowers parents and individualizes their children’s education.

We also explained, many times, the method we use to calculate student enrollment. In fact, we provided the auditor’s office with a chart, outlining the method and the resulting calculations. Those calculations are in line with other school districts. They were also accepted, year after year, by the State Department of Education. If the State Auditor understood how those calculations are made and reported, she would understand why we don’t owe $8.9 million.

We will be providing a point by point response within 24 hours, but once you cut through the theatrics of today’s announcement, the conclusion of the report calls for changes to the law; it does not assert that laws have been broken. Policy makers should be cautious about believing politicians over parents.

Around 4 p.m. Friday, Epic released a 132-page response to the full report from Byrd’s office. Epic’s response is available here.

Stitt, Hofmeister release statements

Stitt and State Superintendent for Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister released statements about the Epic audit late Thursday in a joint email from the governor’s office.

Stitt said his office was still reviewing the audit, but he called the initial findings “concerning.”

“Our state has recently invested in public education at the highest levels in our state’s history, and Oklahomans deserve accountability and transparency on how their hard-earned tax dollars are being spent,” Stitt said. “I am grateful for Auditor Byrd’s extensive work on this report and agree that her findings are not representative of all public charter schools or alternative forms of education. We know parents want educational options, especially in light of how education has shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic. We expect every Oklahoma student to have access to high quality options that are transparent about their performance and accountable to taxpayers.”

Hofmeister said “Oklahomans deserve better” than what the audit appeared to show.

“In an education environment where every dollar is being stretched to the limit, these findings are deeply disturbing,” Hofmeister said. “It is one thing for a public school to utilize the services of a private vendor, which is common practice, but when that private vendor operates the school in question and can manipulate that structure to obfuscate or mislead, there is something systematically wrong. Oklahomans deserve better.”

But Hofmeister also acknowledged the large number of families who have chosen to enroll their children in alternative online schools such as Epic.

“As the coronavirus pandemic has made clear, there is no question that virtual instruction and innovative models are important options for many students and families,” Hofmeister said. “These changes are rapidly transforming the education landscape and it is critical that laws, policies and infrastructure keep pace to ensure transparency and accountability. We will closely examine the most appropriate steps moving forward in consultation with the state auditor and other state officials.”

Read the full Epic audit

(Update: This story was updated at 4:40 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 1, to include the statement from Hickman. It was updated again at 5:28 p.m. to include statements from Stitt and Hofmeister. It was updated a final time at 4:30 p.m. Friday, Oct. 2, to include a link to Epic’s full response to the audit.)