Oklahoma’s 77 county treasurers are holding $80 million of property tax payments in escrow that they cannot immediately apportion to school districts, technology centers and county health departments owing to valuation disputes between energy companies and county assessors.

The complicated and contentious situation is unsustainable, some state legislators say, with school districts unable to leverage anticipated tax revenues for bond projects and some companies complaining that their property is being assessed differently across county lines, depending upon what formula sticks them with the biggest bill and brings counties the most revenue.

Toss in concerns over a third-party assessment firm with nearly four dozen county contracts, and you have an issue that was the focus of a Sept. 22 interim study and that could be a major policy initiative for the 2022 legislative session.

“This particular issue has created a tremendous amount of instability across our state for all parties involved, whether it’s industries, counties or school districts,” Mark Yates, a lobbyist representing renewable energy companies, told NonDoc. “This has been playing our for a number of years.”

Northern Oklahoma Rep. John Pfeiffer (R-Orlando) said he became aware of the issue’s magnitude about five years ago.

“It’s really starting to affect a lot of school districts across the state,” Pfeiffer said. “They’re the ones that get caught in the middle.”

‘What a gut punch that is to the schools’

Over the last decade, the net assessed value of property within the Minco School District, located in Canadian, Caddo and Grady counties, climbed from $13 million to $63 million owing to a NextEra Energy wind farm development. Higher anticipated taxes on the property — called ad valorem taxes — allowed the district to sell bonds and finance the construction of a new high school, middle school and fine arts auditorium, among other things.

However, during the Sept. 22 interim study on Oklahoma property tax protests, Minco Schools Superintendent Kevin Sims said recent challenges by the energy company have contributed to heavy losses for his district.

“In August or September of 2020, I had meetings with NextEra officials, and they informed me that there would be a protest of the assessed valuations,” Sims said. “I asked them what the amount they were protesting was. The amount protested was 70 percent of value of what our assessor assessed.”

NextEra’s Minco I wind farm achieved commercial operation in 2010, with Minco II reaching operation in 2011. Sims said that from the 2020-21 school year alone, $1.5 million in protested taxes are stuck in escrow and currently unaccessible to the district.

“The protest has had a very negative impact on the Minco Public School District financially. There’s no way around that,” Sims said “We’re going to continue on. We’re going to be diligent. We hope that there’s a solution to avoid such protests in the future.”

It can take years to settle tax protests that challenge the valuation of property owned by petroleum or renewable energy companies.

During the Sept. 22 study, Noble County Assessor Mandy Snyder represented the Oklahoma County Assessors Association and said county treasurers currently are holding $80 million of tax payments in escrow.

While some portion of that money will eventually be paid in taxes, it lingers in escrow during the protest lawsuits. That means the money cannot be apportioned to school districts and other operations that receive ad valorem percentages, such as fire departments, law enforcement agencies, ambulance districts, libraries, county health departments and some rural hospital districts.

Snyder reached out to impacted counties for information prior to the interim study and received responses from 40 counties with more than 100 school districts.

“Can you imagine what a gut punch that is to the schools?” Snyder asked during the study. “Our kids that are missing out on technology and books and important things that they need because the budget’s just short and the money is held up in escrow.”

How Oklahoma property tax protests work

To kick off the Sept. 22 interim study, Snyder explained the ad valorem tax assessment and protest processes by assessing the value of the table at which lawmakers were seated.

“The taxpayer comes in and tells me that he believes this table is worth $5,000, and they have to report that to the county assessor,” Snyder said. “In this county, we’re going to assume an assessment ratio of 10 percent and a tax rate of 1 (percent). So, that $5,000 value of this table has an assessed value of $500 and a tax of approximately $50.”

Snyder said the county assessor — or a contracted third party expert — then looks at the property themselves to come up with a value they believe is fair based on factors that include:

- cost of materials and labor that went into building the table;

- the size and utility of the table in comparison to the price of similar tables on the market;

- any kind of income the table could potentially generate.

“After we look at those three approaches, we’re going to value that table and, in this scenario, we’re going to say the assessor believed this table was worth $10,000,” Snyder said. “Using the same ratio and tax rate, that would be an estimated tax of $100.”

If the owner of the table wanted to dispute the difference in valuation, they would have 30 days to file an informal protest with the county assessor using a form from the Oklahoma Tax Commission that requests evidence to support the protest.

“That’s simply a meeting between the county assessor and the taxpayer, and we’re going to talk about the value of the property,” Snyder said. “We’re going to try to come up with some answers between the two of us.”

If the taxpayer and assessor cannot agree on a valuation, the taxpayer has 15 days from the assessor’s decision to file an appeal with the County Board of Equalization. Once that board makes its decision, either the taxpayer or assessor can file a lawsuit in district court if they still disagree on the value.

When a company that has filed a protest goes to pay its taxes for the year, it can file a “pay under protest” form. That form essentially tells the county treasurer that the county must hold the money in escrow and must not apportion it to school districts or other government services.

But that process can present issues, Snyder said, as assessors throughout the state work to certify values by August. That’s roughly the same time that schools and counties are finalizing their budgets.

“The full $1,000 assessed that the assessor believes was a fair value is included in those values. That leaves the schools to believe that they will be receiving their full portion of that $100,” Snyder said. “It also leaves (the) state aid (formula) to believe that the schools will be receiving this money locally, so they don’t include it in their state aid funds. But because it’s under protest, it has to sit in an account and cannot be apportioned out to the counties or the schools.”

The money held in escrow generates interest, and if a company wins the protest in court, it receives the interest back.

“They can actually make money if it comes out in their favor,” Snyder said.

Snyder said the $100 in her hypothetical example may not seem like much, but the real issue at hand involves property such as $50 million oil pipelines and $300 million wind farms. In southeast Oklahoma’s Pittsburg County, Snyder said two different companies are involved in a protest that equates to about $58 million of value, by the assessor’s estimation.

“The companies are asking for $9 million,” Snyder said. “That’s approximately an 84 percent decrease in value.”

Snyder said Dewey County, in northwest Oklahoma, is currently in litigation with four out of five wind farms in the area.

“When it comes to wind in particular, most of those farms in Oklahoma were at one time part of the five-year manufacturing exemption program. That means that 1 percent of our income taxes — yours and mine — went into the fund to pay the taxes for those companies,” Snyder said. “There’s no protest that I know of of value when Oklahomans were paying those taxes.”

But when the state stopped footing the local ad valorem tax bill, Snyder said companies began filing protests and saying that various parts of the wind turbines had depreciated in value at different rates.

Seeking a standard valuation methodology

The Sept. 22 interim study on Oklahoma property tax protests was hosted by four rural legislators: Pfeiffer, Rep. Carl Newton (R-Cherokee), Rep. Dick Lowe (R-Amber) and Rep. Kenton Patzkowsky (R-Balko).

“The right to protest your taxes is guaranteed in the constitution. Everybody has it,” Pfeiffer said. “I think something pointed out during the interim study is that they’re protesting the value, not the taxes. The biggest issue, and the one that’s going to be the most difficult to solve is, how do we reach some sort of agreed-upon methodology so that these things don’t end up in protest year after year? That is going to continue to be the hardest part, because you have two sides that view things very differently.”

Pfeiffer said there have been issues regarding how wind turbines are valued since the industry first came to Oklahoma, dating back to when state law directed the Oklahoma Tax Commission to offer the companies manufacturing exemptions.

“There are discrepancies between how the Tax Commission depreciated assets as opposed to how the counties depreciated assets. It has really popped up the last handful of years as we see more wind farms roll off the manufacturing exemptions,” Pfeiffer said. “[The companies’] stance is that the initial values that the Tax Commission placed on them were too high to begin with, but since OTC was technically the payer of those ad valorem taxes, they didn’t have standing to protest the value when OTC was covering the bill.”

Former Oklahoma Sen. Bryce Marlatt is a partner in a company that provides services for petroleum, wind and transmission line companies. He told NonDoc that the lack of consistency in the valuation process makes things difficult for companies, big and small.

“County A is assessing everything at $10 million, and County B has the exact same equipment across the boarder and they’re saying it’s a $5 million valuation. How is that valuation different?” Marlatt said. “People think that if you’re in a certain business you automatically have a lot of money, and that’s not the case. You’ve got a tremendous amount of assets to maintain, and you’ve got to reinvest. Tax rates have a big effect on that.”

Marlatt said oil and gas equipment is built for mobility and is constantly moving between job locations, a situation he believes can be taken advantage of.

“It might be in Woodward today and be there for two weeks. Then it may be in Chickasha and then Elk City,” Marlatt said. “I’m well aware we’ve got to pay taxes, and it needs to be taxed wherever it’s at. But, you start to figure out what counties are trying to take advantage of the situation and what counties are trying to do it right. I’m not saying that all counties are doing it wrong or that they’re targeting a certain group. I’m saying there’s inconsistency in how they assess the property, sometimes within the county, and most times from county to county it’s different.”

Concerns over differences in valuations have also been stoked by some county assessors’ use of third-party consultants to assist with more technical valuations, such as the depreciation of wind turbine blades.

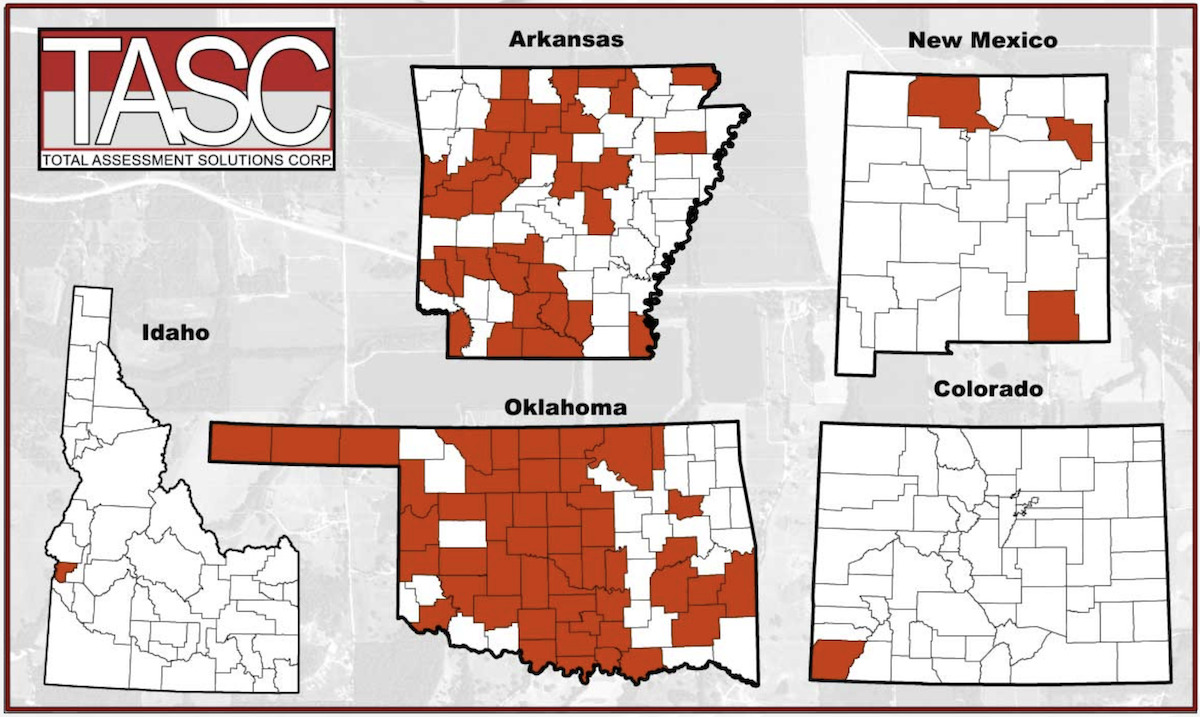

Yates, a former Oklahoma Advanced Power Alliance executive who still represents the organization under his employment with Cornerstone Government Affairs, expressed concern that 46 of Oklahoma’s 77 counties use a single third-party consultant: Total Assessment Solutions Corp., or TASC.

“We have 77 elected county assessors, and the vast majority of these counties are consulting with a third-party consultant. Does that whole process need to be revamped and re-thought?” Yates hypothesized. “Should that perhaps be a state process in which the state enters into a contract with a third-party consultant to do this work on behalf of the counties? Should we look at additional training or credentialing for some of the third parties that are doing this work? When you look at oil and gas and wind facilities, these are some of the largest investments in our state. You need to have the technical experience to deal with placing value on these assets. They’re very unique, and their attributes are unique.”

Yates said the industry has repeatedly pointed out what they believe are fundamental flaws in how TASC and the company’s personal property appraisal manager, Jerry Wisdom, arrive at the values of wind facilities.

Yates recalled a meeting to discuss these concerns prior to the pandemic with stakeholders that included industry representatives, the State Auditor and Inspector’s Office, leadership from the County Assessor Association of Oklahoma and Wisdom of TASC.

“(Wisdom) throws out, ‘Look, there are three approaches to value. There’s a cost approach, an income approach and a comp for sales. But, I prefer the fourth approach, which is I have a number, you have a number and let’s just meet in the middle,'” Yates recalled. “At which point the entire room looked around at each other like, ‘That’s the problem!’ Ultimately, that is not an approach.'”

Yates suggested that lines of communication between affected parties — counties, school districts, state agencies and private companies — could improve.

“All of that is very important so that nobody is caught off guard if there is to be a protest that arises or a disputed amount of tax,” Yates said.

Marlatt said he doesn’t know what the answer to the complicated issue of Oklahoma property tax protests will be, but he agreed that communication would go a long way.

“I do know that we can always do better. Whether that’s through education on the impacted industries or whether that’s through education on the assessors,” Marlatt said. “I do know that healthy dialogue would go a long ways in this whole process.”

Cody Bannister, the senior vice president of communications for the Oklahoma Petroleum Alliance, emphasized that none of his organization’s members are trying to avoid paying their share of taxes.

“The oil and gas industry is the largest taxpayer in the state,” Bannister said. “We account for 25 percent of all the taxes paid. We’ve never shied away from the fact that we are the largest taxpayer, and we want to make sure we’re paying the taxes that we owe.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘They undercut it so far that it’s not even a realistic value…’

Based in Arkansas with a branch office in Ada, TASC has assessment contracts with 82 counties across five states. A graphic on the company’s website shows contracts with four dozen Oklahoma counties.

TASC personal property appraisal manager Jerry Wisdom spoke during the Sept. 22 interim study, telling lawmakers that the assessing process is complicated by companies’ failure to provide information upfront.

“It’s a fight for the documents. Everything is contained confidential with the assessor’s office. There’s no reason for these companies not to provide the data,” Wisdom said. “They only don’t want to provide it because they can stave, stall and send it to court, in my opinion.”

Stephens County Assessor Dana Buchanan told NonDoc that her office contracts with TASC to be their third-party assessor for oil and gas valuations, as the company has the valuation knowledge on technical pieces of equipment.

“Our oil and gas companies, while for the most part are very forthcoming, not all of them are. We’ve picked up millions by hiring an outside company.” Buchanan said. “Some assessors hire outside companies to value their commercial property. Some assessors hire outside companies to value their real estate. I do all that in-house. (But) I haven’t got that experience for oil and gas, and there’s nothing worse than someone who doesn’t know what they’re appraising to do that appraisal. Hiring a specialist — someone who knows what they’re doing as a specialty — that’s the best way to do it.”

The Stephens County Board of Commissioners covers legal fees surrounding protests, but that is not the case across the whole state, and there could come a time where that is no longer the case for Stephens County, Buchanan said.

While Buchanan said she could not speak about specific companies involved in protests owing to confidentiality law, she said two oil and gas companies are currently protesting valuations in the county.

“My biggest problem that I see is they undercut so far when you give them a value. They undercut it so far that it’s not even a realistic value that they give,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan emphasized that she wants to be fair and equal to all taxpayers, but she said the inability to share information with other county assessors can be a hindrance.

“We want to be equally knowledgable and be able to share knowledge so that everyone’s treated fairly,” Buchanan said. “I don’t know that all companies don’t want that, but some of them really stand their ground on it. They don’t want us to talk.”

As her county’s assessor since 2015, Buchanan said the continual protests leave her disappointed.

“Ten percent of their tax bill is not going to shut this county down. But it’s taking away [resources] out of schools,” Buchanan said. “These crazy values that they’re throwing at us don’t do anything but hurt these schools.”

(Correction: This article was updated at 11:05 a.m. Thursday, Oct. 14, to correct reference to Bryce Marlatt’s company.)