On Aug. 9, as U.S. forces withdrew from Afghanistan and the Taliban swept through the city behind them, Oklahoma City art gallery owner Susan McCalmont received a distressing message from a friend in Kabul.

“Susan,” Hasina Aimaq wrote, “the security is getting very worse. All people are moving. I really don’t know what to do. I have to move immediately. I have to find a way to get out of here.”

McCalmont and Aimaq met two years earlier through the Institute for Economic Empowerment for Women, a nonprofit founded by businesswoman and former congressional candidate Terry Neese.

McCalmont had been talking to Aimaq throughout July, initially to coordinate a show of Afghan women’s art and then to try to find a way for Aimaq and her family to come to the U.S. as a precautionary measure in anticipation of the American withdrawal.

Aimaq, an entrepreneur, businesswoman and fashion designer, ran an organization that helped Afghan women turn their skills into businesses. Her work had already drawn threats and intimidation from the Taliban — a few years ago, one of her colleagues was kidnapped and Aimaq escaped only by hiding in a bathroom — so she knew she would have a target on her back after the Americans left.

When Aimaq turned to McCalmont for help in August, however, McCalmont did not know what she could do or whom to call. She got in touch with U.S. Sen. James Lankford’s office, which normally would be able to pull strings to help with an immigration matter. But with Kabul International Airport flooded with people desperate to leave, not even a senator could do much to get Aimaq’s family on one of the few flights out of the country.

“Susan, they’ve reached Kabul,” Aimaq texted on Aug. 15. “Susan, I can’t express my feelings. All people are crying. I thought there was a bit more time. Susan, my kids are very scared. See the news. They’re at the palace. Just stay in touch with me. I’m really scared. My mind is not working right now. I don’t know what to do.”

The Taliban’s arrival in Kabul, after sweeping through the country’s more rural provinces, had happened suddenly and sooner than expected. The day had started out normally for Aimaq. As she stopped by the bank, she heard gunshots in the street.

“Everyone was rushing, and we had no idea what’s happening,” she recalled in an interview.

The phones in the area had stopped working as Aimaq made her way home — a four-hour journey that usually took 25 minutes. Once home, she hunkered down with her mother, husband and two small children, preparing for the worst.

“I said to my husband, ‘Definitely they will come and they will kill me,’” she recalled. “‘But one thing I will do is that when the door is knocked, I’m requesting you that you have to keep your eyes on my kids. You have to lock yourself and my mother in a room, and then I will go, because I don’t want my kids to see that they kill their mother.’ That was the kind of thinking that I had.”

After two nights of this fear and hopelessness, Aimaq received a call early one morning to say there were seats for her family on a flight, but they had to leave for the airport immediately.

Back in Oklahoma, McCalmont had succeeded in triggering a series of events that, through a long string of unlikely connections, helped Aimaq and several other Afghans escape the country in those chaotic days. These efforts coincided with another mobilization happening in Oklahoma as the state prepared to welcome its largest refugee population in decades.

The story of this undertaking, which is ongoing, reveals the unlikely and at times haphazard process through which Oklahomans at all levels — from senior staff in the governor’s office to volunteers sorting piles of donations — have responded to an international crisis.

‘Honestly, it was a Hail Mary’

In desperation, McCalmont had been contacting almost everyone she knew, on the off-chance someone might have a useful connection.

Among this flurry of calls, the one that finally made a difference went, improbably, to Amber Sharples, the executive director of the Oklahoma Arts Council.

Like McCalmont, Sharples did not know where to go with the information. However, it happened that she recently had been working closely with Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt’s chief of staff, Bond Payne, to organize an exhibit for the Mexican artist José Sacal in the Governor’s Gallery at the Capitol. Payne, she thought, might at least know whom to call.

“Honestly, it was a Hail Mary. And, in fact, I almost hesitated to send it.” Sharples recalled, saying she worried Payne might find the request an overstep of their limited acquaintance.

Payne turned out to be sympathetic, but he was also stumped at first.

“I didn’t know where to go with the info I had,” Payne recalled. “I didn’t know where to route it or what I could do to help. Then, over the weekend, I’m watching these images on TV of Kabul falling, and it just weighed heavy on me. I was just like, man, I can’t believe there’s nothing I can do. And then Sunday night, it was just kind of like a lightbulb went off and I thought to call Mr. Azima.”

This is where the long string of tenuous social connections really unfurls.

Farhad Azima was born in Iran and is now based in Kansas City, Missouri. He has spent the bulk of his career in the aviation business, running cargo and charter airlines.

If you Google Azima’s name, you’ll get a waterfall of results outlining a colorful past — allegations of secret dealings with the CIA, rumors that he transported the weapons at the heart of the Iran Contra scandal, tales of entanglement in a multi-million-dollar international corruption case.

A recent New York Times article about a hacking case in which Azima was targeted opens with the words, “For decades, Farhad Azima navigated the shadowlands where business blends with intrigue and the limits of the law.”

Payne had met Azima while accompanying Stitt on the governor’s July trip to Azerbaijan, a petroleum-rich former Soviet Republic bordering the Caspian Sea.

“You know, he’s a global businessman,” Payne said of working with Azima. “Very generous. Very well liked, it seems. And I think he’s someone who has operated in political circles and global circles for his entire career, as far as I can tell, and is passionate about refugees and helping people flee oppressive regimes.”

Azima certainly turned out to be a useful contact considering the circumstances, and he was already involved in evacuation efforts in coordination with the American University in Afghanistan. By the time Payne reached out to Azima, the governor’s office had been contacted by a number of other people in the state with connections in Afghanistan — many of them members of the National Guard who had served there.

“We were getting cold calls,” Payne said. “National Guardsmen. Got a call from our D.C. director, who had been contacted by a friend at the Hudson Institute. Turns out this group of Christians was associated with an Oklahoma church, so we added them to our list because of that connection. There was no system to it. These were just people grasping at straws because they thought maybe we could do something to help.”

The governor’s office sent Azima a list of names, and he began working with contacts on the ground in Afghanistan.

In an interview with NonDoc, Azima was vague about what sort of machinations were actually involved. Asked to describe the extent of his involvement, he chuckled and said, “I’ll send that to my press agent to answer,” referring to the governor’s communications chief Charlie Hannema, who had organized the phone interview and was sitting in on the conversation.

“I’d say it was a collaborative effort,” Hannema said. “Mr. Azima helped us to open some doors that we never would have been able to open just by ourselves.”

Azima added, “Mr. Payne, he coined a new phrase: ‘Our friends outside of the regular government.’”

Getting people to the airport in time to fly them out proved challenging not only because it involved passing multiple Taliban checkpoints but also because of the more mundane-yet-vital issue of getting paperwork in order.

Aimaq’s family, for instance, had given their passports to a friend to take to the Indian embassy in an attempt to get a visa. But when the Taliban entered the city, the embassy went into lockdown with the friend and the passports inside.

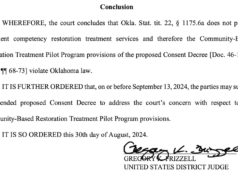

In what turned out to be a pivotal suggestion, Azima said it might be useful if the people on the list had a letter from Oklahoma’s governor to vouch for them. A letter was sent over, on Stitt’s official letterhead, requesting they be given safe passage.

Meanwhile, the governor’s office turned into a round-the-clock operation, with one staffer spending the night in the office.

“I forget what that Kevin Costner movie was,” Payne said, searching for a comparison. “It felt very real-time. I felt like I was in the action. I was getting calls from Hasina (Aimaq) asking if they should go to the airport or not. Like, she’s asking me for advice on something that could be putting her life in jeopardy. It was just, ‘Man, Hasina, I cannot answer that question for you.’”

Afghan refugees face checkpoints, gunshots and uncertainty

When Aimaq got word that she and her family needed to leave immediately to catch the flight arranged by Azima, she covered her face and instructed her children to say they were going to their grandmother’s house if anybody asked. She printed out Stitt’s letter, she gave the house keys to neighbors, and the family left without any luggage or possessions.

Thousands of people had gathered at the Kabul airport, and Taliban soldiers manned multiple checkpoints at the entrances. Three times, Aimaq’s husband asked the Taliban guards to let them in or point them in the right direction, but they refused to talk to him. So, despite her family’s protests, Aimaq decided to try herself.

With Stitt’s letter tucked into her sleeve, she approached the Taliban soldiers. One of them hit her and said he wouldn’t talk to a woman. Another fired a shot near her feet and said the next shot would be in her forehead.

“I said OK, go ahead,” Aimaq recalled. “If you stop me, I won’t stop. I have to go because my family is there.”

Then one of the Taliban, seeing this scene unfold, asked if she had a male with her, then told her to go get her family and he would let them through that checkpoint.

“I’m always thankful to him,” Aimaq said.

Past the first obstacle, the family was herded into a corner where they waited for several hours in the sun without food or water. Aimaq told her kids that they were playing a game and the gunshots in the air were balloons.

“Mom, I don’t want to play this game,” her 3-year-old daughter said.

Finally, Aimaq decided they would have to push into the airport. The scene was chaotic, with people rushing and crowding and shouting. She tried to show Stitt’s letter to U.S. soldiers and anyone else who looked official, but nobody seemed to take any notice. She told her family to wait by a wall and asked her husband to cover the children’s eyes as she went to find someone to let them on the flight.

“I told them, ‘If I come back, I’ll take you with me. If not, then that’s the end,’” she said.

Finally, she found someone who had her name on a list, and two Taliban soldiers came to escort the family through the crushing crowd. Aimaq’s elderly mother fell down at one point, and Aimaq also got stuck on the ground, cradling her daughter. One of the Taliban solidiers shouted at the others not to scare the children and told Aimaq to give him her child to carry. Not knowing what else to do, she handed her daughter over to the man, and, to her relief, he carried her to safety.

At last the family boarded the plane, but Aimaq said she did not feel safe or hopeful until they had landed in Qatar and officials, to her surprise, accepted Stitt’s letter in lieu of passports to allow her family into the country.

‘We’re deprived of our basic rights, facilities and resources’

In the end, Aimaq and her family were among 69 Afghans who made it out of the country in those final days thanks to the last-minute scramble coordinated by the governor’s office.

Others were not so lucky.

Like Susan McCalmont, Cathy Cruzan, who has been involved in the Institute for Economic Empowerment of Women for several years and serves on its board, had contacts in Afghanistan because of her work with the organization. A number of Afghan women who have participated in IEEW’s programs are still in the country and have had to shut down their businesses. Some have had to go into hiding. One woman has been able to make it out and to the U.S., but her husband and children are stuck in Afghanistan.

Recently, Cruzan received an email from one of the women in Afghanistan:

I’m sorry to bother you every few days and apologize for disturbing your work, but I am helpless. I disturb your time because of bad circumstances and bad situations, and I know you understand as a woman. As you are aware through the social media, the Taliban evacuated the prisons, criminals, murderers, and thieves, but the prisons are now full of journalists, social activists, civil society activists, women’s rights…. Please continue to support me.

We’re in a worse situation now. We’re deprived of our basic rights, facilities and resources. This situation has made life difficult for everyone, especially for me and my family.

“I think the key here is there are a lot of women — families — that want out that can’t get out,” Cruzan said. “[They] are reaching out to whatever contacts they can.”

Cruzan has been in contact with some of these women, but supporting them is easier said than done. Cash remains in short supply in Afghanistan, making it difficult to send money. Flights are exorbitantly expensive anyway, so finding places to go also remains a challenge.

One woman Cruzan has been in touch with, whose first name is Nazila, had her name sent to the governor’s office along with a number of other IEEW contacts, but she never heard back from anyone involved in that effort, Cruzan said.

But even if she had been on the list, she might have struggled to get into the airport. As it was, she spent 38 hours outside the airport in a convoy Cruzan had helped her get on, only to turn back after a suicide bomb detonated nearby.

(Hannema told NonDoc that the governor’s team received Nazila’s name “the day after the terrorist attack at the Kabul airport, which significantly altered the landscape and what we were able to accomplish. We were not able to verify that she had the needed documentation and had to triage our efforts on the people we knew we could accommodate.”)

Nazila did ultimately manage to leave Afghanistan, but not until October. Beyond saying Nazila had to stand in line for days, Cruzan did not want to share details of how her friend got out, so as not to jeopardize anyone else using the same avenues. Nazila is currently in Rwanda, waiting for her application to come to the U.S. to be processed. Cruzan said Nazila hopes to come to Oklahoma, if she can.

Like many who did not make it out of the country before the Taliban takeover, Nazila qualifies for refugee status in the U.S. under programs established specifically for Afghan immigrants. But the American immigration process, which can be painfully slow at the best of times, has been flooded with applications for special visas that have been instituted Afghan refugees.

“There are so many lives right now, especially if they qualify for status in the United States, they’re in limbo,” Cruzan said. “And you can’t even check on where is the status of the application.”

Payne, too, expressed frustration with the federal government’s handling of evacuation efforts.

“Why did we even have to help these people?” Payne said he remembers thinking. “It’s like, they shouldn’t have needed our help. The U.S. government should have been taking care of these people.”

The sluggishness Payne, Cruzan and others have found surprising and frustrating is nothing new, however. Long before the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, the special visa program had a backlog of thousands, thanks to various forms of red tape, understaffing and disorganization.

A June 2020 report by the State Department’s Office of the Inspector General found that the program lacked a central database, operated on its same staffing levels from 2016, and — since 2017 — lacked a “senior coordinating official,” who is the person tasked with coordinating the many offices and departments involved in approving the visas.

“I was disappointed that there wasn’t a plan to evacuate Americans, our allies (and) people who put their lives at risk for our cause, our values,” Payne said. “I think it does a lot of damage to the United States, its credibility, its brand.”

‘There is a connotation of patriotism’

As Americans watched the frantic scenes unfolding in Kabul, officials at Catholic Charities in OKC were figuring out how many of the 37,000 people flooding out of the country and into the U.S. refugee system Oklahoma might be able to accommodate.

The number brought to Oklahoma — 1,800 people, or about 350 families — stands as the third-highest number of Afghan refugees accepted by any state in the country, behind only California and Texas. It is also larger than Catholic Charities, which is federally contracted to handle all refugee resettlement in the state, initially had ventured.

“When we originally proposed the number, it was much much smaller than 1,800,” recalled Jessi Riesenberg, senior director of development and outreach at Caltholic Charities. “And the governor actually came back to us and said, ‘I think Oklahoma can do better. I think we should welcome more people. We will support your organization and your efforts to resettle if you up your number.’”

The Stitt administration’s enthusiasm surprised some.

Just last year, Stitt authored an op-ed expressing support for President Donald Trump’s move to set a historically low cap of 18,000 on the number of refugees allowed into the U.S. and said he favored allowing no more than roughly 220 into Oklahoma in 2020.

Jessi Riesenberg, the senior director of development and outreach at Catholic Charities, said the governor’s thinking might have been shifted by conversations with leaders of her organization, which she recalls happening shortly after the op-ed was published.

“We called his staff, we called him. We had conversations to educate him around, like, what was the refugee process,” she said. “And he was really surprised that he had so much to learn and to know about this process. And I think that additional education and understanding really helped. And so we’ve seen a lot of wonderful support of our refugee program since.”

Following that conversation, Riesenberg said, “that comment about capping it really died away.”

Hannema, the governor’s spokesman, pointed to more practical considerations.

“My understanding is that in 2020 the governor aligned the percentage of total refugees Oklahoma could accept with Oklahoma’s percentage of the national population to ensure we had sufficient resources,” Hannema said in an email. “The number of Afghan refugees Oklahoma could accept was generated based on what the nonprofit and philanthropic communities felt they could accommodate.”

Riesenberg speculated that the state’s openness to Afghan refugees also has to do with the particular political circumstances.

“I think there is a connotation of patriotism around this particular effort, because many, many more people recognize what the Afghan people helped our troops do when our troops were present in their country,” she said. “And many Oklahomans, especially this being such a heavily military state, had personal ties and connections with families in Afghanistan. So I think that makes a huge difference in (…) humanizing. And while I’m not necessarily for humanizing someone because you have a personal connection — we should humanize everybody, because we’re all the same — but the reality of it is the patriotism around it and the real physical family connections of these people helped individuals that we know, really is some of that thought process.”

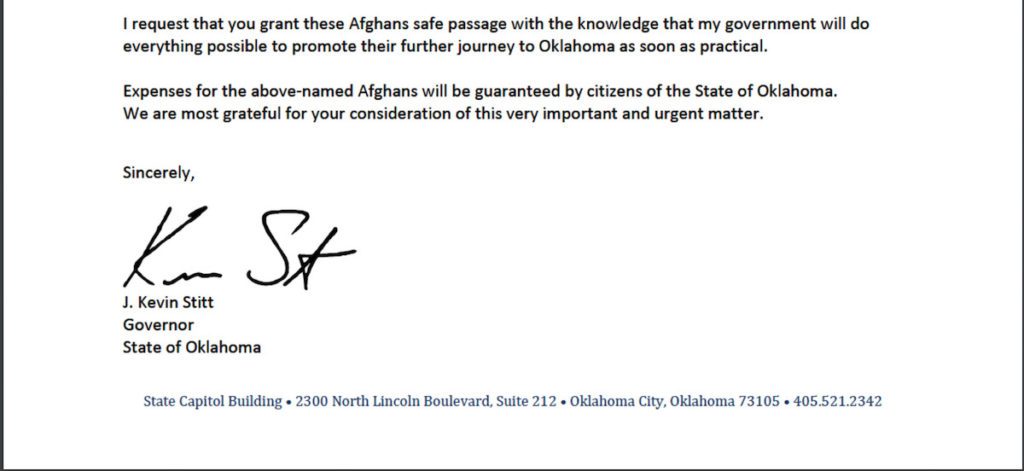

Some in Stitt’s political party have not been swayed by patriotic considerations. On Sept. 4, John Bennett, chairman of the Oklahoma Republican Party, posted a video on Facebook opposing the resettlement.

“There is no way we can properly vet these people,” said Bennett, a former state legislator who has railed against Islam throughout his political career. “If the government says otherwise, they are lying to you. Why would we allow the same enemy we’ve been fighting for 20 years in the War on Terror on American soil?”

Payne declined to comment on Bennett’s position, saying, “I don’t want to make news here.”

Many of Stitt’s fellow Republicans have been at least cautiously supportive of the Afghan resettlement.

“We rely on Gov. Stitt. That’s really an executive decision, it’s not the Legislature’s,” said House Speaker Charles McCall (R-Atoka). “But we have to trust that the governor looked at those details and was comfortable with that. But what I can speak to in terms of where I believe most Oklahomans are on that issue (is) they love people. We are the cheerful state. But there was not much information given to them as to the background or the vetting process on these folks that are going to be part of our state.”

Jon Echols, the House majority floor leader, expressed a similar sentiment.

“From my faith, I think we need to show them the Oklahoma welcome that they deserve,” Echols said, referencing the Book of Matthew. “I absolutely share concerns that the federal government didn’t do a good job in their vetting process. I think in the future we need to allow states more opportunities in the vetting process. But let’s make sure we recognize what the (situation of) Afghan refugees is. These are people that are going through the legal refugee process. These are not people that are trying to come in and break our laws. These are people that are fleeing a totalitarian and awful and horrible government.”

The Department of Homeland Security has said the vetting process for Afghan refugees “involves biometric and biographic screenings conducted by intelligence, law enforcement, and counterterrorism professionals from the Departments of Homeland Security and Defense, as well as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), and additional Intelligence Community (IC) partners.”

Riesenberg said she thinks Oklahomans should understand that the refugees arriving in the state are undergoing a lengthy and complicated process.

“For readers who are hesitant or understand this to be a little bit foreign and ‘What’s going on? and ‘Are the people we’re bringing over here OK?’ No corners are being cut,” she said. “And because the standard is to make sure that we don’t cut corners — it’s client-centric but it’s also community-centric — so there’s no corners being cut, so that generally makes things take a little while, and that’s OK.”

‘A fast and furious process’

As of Dec. 5, more than 860 Afghan refugees had arrived in Oklahoma. The rest of the 1,800 should arrive in the coming months, though the timeline isn’t clear, according to Riesenberg. It will be the largest resettlement the state has seen in recent memory.

“The last massive effort in our refugee resettlement process was when we brought the Vietnamese to Oklahoma City,” Riesenberg said. “So that was a massive effort and brought in a huge cultural diversity to our city. So we’ve done it before, and we’re doing it again. It just happens to be 40 years later.”

Managing the Afghan resettlement has not just been a matter of dusting off an old playbook, however. It has also required a significant, rapid buildup of capacity.

During the Trump administration, Riesenberg said, the arrival of refugees in the state dwindled significantly, to about 25 or 50 a year — never coming anywhere close to the cap of 220 Stitt had promoted. Even before that, the state might see only around 250 refugee arrivals “in a good year,” she said.

Riesenberg described the effort to get ready for the Afghan resettlement as “a fast and furious process.” Right off the bat, for instance, Catholic Charities onboarded 11 new staff members in 10 days.

The arrival process can be similarly fast and furious.

“We get anywhere from 24 to 72 hours of notice,” Riesenberg said, “and basically all that we receive is the demographic information for the head of household and each one of the family members and what time their plane comes in. And that’s pretty much it.”

The arriving families are met at the airport by a volunteer and taken to temporary housing — often a hotel — where they will start the arduous process of starting a new life from scratch.

Mike Korenblit, founder of the Respect Diversity Foundation, who has been working as a volunteer to meet arriving families at the airport, said the people he has greeted are excited, grateful and a bit shell-shocked. Not only did most have a frightening and traumatic experience leaving Afghanistan, they are also landing in a place where they have no connections and little knowledge.

“They’re thinking, ‘What’s Oklahoma?’” he said.

Riesenberg commented that she believes Americans tend to misestimate refugees’ eagerness to be in the United States.

“It’s maybe worth noting that, for the most part, every person that we are going to resettle would rather have stayed in a safe, stable, secure Afghanistan,” she said. “It’s not like everyone was just sitting around Afghanistan just waiting for the shoe to drop so they could come to America. That’s just a misconception of the desire of the population.”

Once here, Afghan refugees are starting life from scratch. Providing them with even basic necessities has been an enormous undertaking for the local nonprofit community.

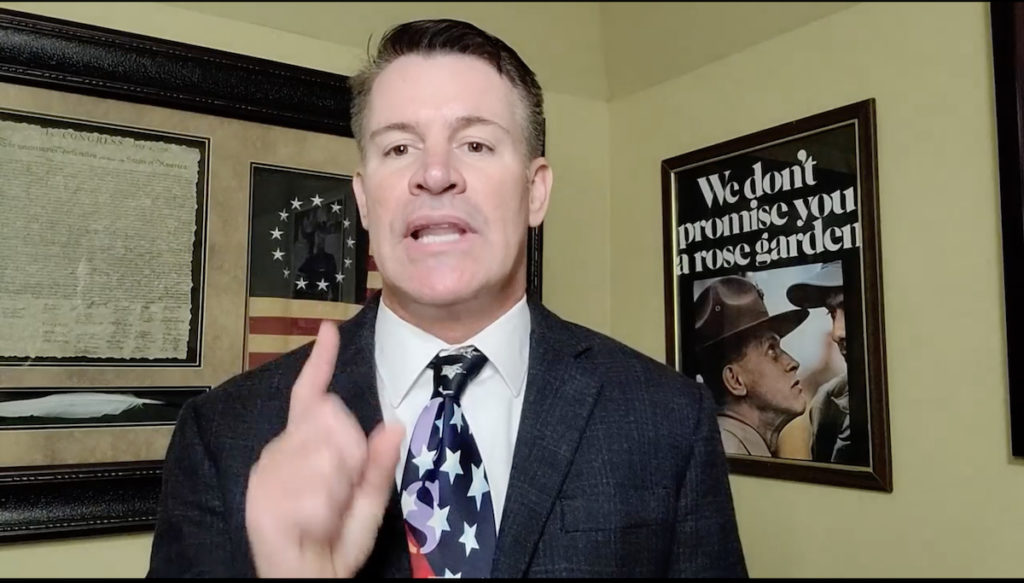

The Oklahoma chapter of the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) has been working to assist the new refugees when they arrive. Challenges have ranged from collecting donations to finding translators who can speak Pashto or Dari, the two most common languages in Afghanistan.

There are a multitude of moving pieces to keep track of: getting meals delivered, finding new clothes for those who arrive without anything, putting together welcome kits with hygiene items and other necessities. And that’s before even starting the complicated process of assisting these new Oklahomans as they get IDs, open bank accounts and deal with all sorts of paperwork.

“This is really kind of pushing the boundaries of what we traditionally have done, because we’ve never seen anything quite like this,” said Veronica Laizure, the civil rights director for CAIR Oklahoma. “But the flip side of that is that this is a historic and monumental undertaking that the entire state is going through.”

Laizure said there has been an enormous outpouring of concern and help from the community. At one point in September, CAIR had to stop taking donations because its office was overflowing with everything that had come in.

Likewise, a huge range of groups in the community have pitched in. Period OKC and the Junior League of Oklahoma City helped mobilize a drive to collect menstrual supplies. The Equity Brewing Company and the clothes-rental company Library OKC brought in a whole moving truck of clothing donations. The Deer Creek Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and Temple B’nai Israel have both helped to put together backpack kits for children.

For Korenblit, who is the son of Holocaust survivors, the work is very personal.

“When I was there for the very first family and I saw them walking through, I didn’t see them,” he said. “What I saw was my grandparents and my mother and father and all their brothers and sisters. Only it wasn’t true, because America didn’t open its arms to my parents and the other Jews who were trying to escape the Nazis during World War II.

“So when I saw that family, I was just filled with exhilaration. Saying, ‘You know what? We didn’t do it for the Jews. We didn’t do it for the Syrian refugees. But we are doing it for the Afghan refugees now.’ So that just means the most in the world to me.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘A kind of feeling that I never felt before’

When Aimaq and her family arrived in Qatar, they had nothing with them. “Not even a toothbrush,” Aimaq said.

Once in Qatar, it took a few days to obtain basic supplies. Their clothes were dirty; they hadn’t been able to comb their hair for five days.

They spent two weeks in Qatar, with no word on how long it would take to get into the U.S., they decided to take an offer to go to Canada — a country none of them had ever visited. They are currently in Toronto and, like the arriving refugees in Oklahoma, have been more or less dependent on resources from the government and local charities.

It’s an odd experience for Aimaq, who is used to offering help rather than needing it herself. Even in the days before the Taliban entered Kabul, she was trying to find funding to help people who had fled to the city from the provinces.

“They are asking, ‘What do you need? How can we help you?’ And most of the time I think, ‘I have to tell them that I don’t have anything.’ So how I can ask everything that we need from them? I don’t feel good about it,” she said. “Because when we were in Kabul, we had a good life. I really don’t know how to do that. On one hand. I don’t feel good to receive all of those donations and everything. But, on the other hand, I have to because of my children, to survive here. This is a kind of feeling that I never felt before.”

Aimaq, whose father died when she was just 1 year old, saw her mother experience all kinds of hardship. And it took Aimaq herself many years to build the life she had back home, and now she has to start that process again.

“It seems that I have been newly born,” she said. “So once again I have to go through it, and it will take me years to settle in here. It’s not only about from the financial aspects. It’s not only about that. It’s that how I can make new friends here? How I can adjust in the community? My interactions with the community and all of that? For a human, this is the most important part of life.”

Though the future is full of uncertainties and challenges — “I’m still thinking that I’m just watching a movie,” Aimaq said — she described a recent moment when a glimmer of hope fell on the path ahead.

After several weeks in a single hotel room in Toronto, the family moved into an apartment Nov. 15.

For the first time since they left Afghanistan, they were able to cook a meal and sit down and eat it together.

As they sat down, Aimaq’s mother started crying.

“And she said that after so many days, we managed to sit together to eat,” Aimaq recalled. “And kind of feeling home. And now we have a home. We know where we are going.”