(Update: For an article recapping the April 27 oral arguments in Oklahoma v. Castro Huerta, click here.)

At 10 a.m. Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, a case that Gov. Kevin Stitt’s administration hopes will be its best chance yet at limiting the effects of the court’s 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma.

The McGirt decision, which found that the Muscogee Nation Reservation had never been disestablished by Congress and is therefore still legally Indian Country, gave only federal and tribal courts jurisdiction over major crimes committed by or against tribal citizens on reservation land. Five other reservations in Oklahoma have since been affirmed based on the McGirt precedent, with the result that much of the eastern part of the state is now lies within Indian Country.

Tribal leaders have praised the ruling as an affirmation of tribal sovereignty and an economic opportunity for their citizens. But Stitt has vociferously objected to the McGirt decision, saying it’s the “most pressing issue” facing the state. In recent months, his administration and Attorney General John O’Connor have appealed dozens of cases that had been decided on the basis of McGirt, most of which were denied a Supreme Court hearing.

While the original McGirt case dealt with the prosecution of a tribal citizen, Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta asks who has jurisdiction when a non-Indian is accused of committing a crime against a tribal citizen.

Specifically, it concerns the prosecution of Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, who was sentenced in 2017 to 35 years in prison for the severe neglect of his 5-year-old step daughter, a citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals vacated his conviction in April 2021 on the basis that, according to the McGirt decision, the case did not fall under state jurisdiction. Castro-Huerta has since pleaded guilty to federal charges for the crime.

In its appeal to the Supreme Court, the state calls the decision to vacate “erroneous” and says it “greatly exacerbates the ongoing criminal justice crisis in Oklahoma.”

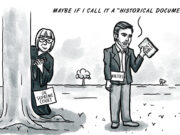

Oklahoma had originally asked the Supreme Court not only to address the jurisdictional issue raised by the Castro-Huerta case but to consider overruling McGirt entirely. In agreeing to hear the Castro-Huerta case, however, the court said it would consider only the specific jurisdictional question regarding Indian defendants and declined to consider a broader overturn.

Audio of Wednesday’s oral arguments will be streamed online.

‘Calamitous’ or ‘overblown’?

In its arguments against McGirt, both in court and in the media, the Stitt administration has framed the case as an issue of public safety.

The results of McGirt “have been calamitous and are worsening by the day,” the state says in its petition.

“The decision in McGirt now drives thousands of crime victims to seek justice from federal and tribal prosecutors whose offices never before handled those demands,” the petition continues. “Numerous crimes are going uninvestigated and unprosecuted, endangering public safety. Federal district courts in Oklahoma are completely overwhelmed.”

Given that the court will not be considering whether to overturn McGirt, however, the question before the justices Wednesday will be more narrow. The state’s petition acknowledges tribal and federal jurisdiction in cases such as Castro-Huerta’s but argues that the state retains concurrent jurisdiction.

“The General Crimes Act provides the federal government with authority to prosecute violations of general federal criminal law where either the defendant or the victim was an Indian and the other party was not,” the petition says. “But this court has never squarely held that states do not have concurrent authority to prosecute non-Indians for state-law crimes committed against Indians in Indian country.”

The appeal argues that denying concurrent jurisdiction would be detrimental to tribal citizens.

“A state’s Indian citizens are entitled to equal protection under the law, including equal access to the resources, protection, and benefits of the State’s criminal-justice system,” it says.

Oklahoma’s tribal nations have argued against concurrent jurisdiction for the state and have contested Stitt’s portrayal of widespread legal chaos in the wake of McGirt.

In a press conference Monday, Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said Stitt has “neither the facts nor the law on his side when it comes to tribal sovereignty.”

An amicus brief filed by the Cherokee Nation (one of a number filed in the case) argues that settled law precludes concurrent state jurisdiction in cases such as the one under question, unless specifically granted by Congress.

“If Gov. Stitt is successful, he wouldn’t only undermine tribal sovereignty among the tribes in Oklahoma that have reservation status,” Hoskin said in the press conference. “He would turn back the clock on jurisdictional law across Indian Country. So he’s really seeking the court to rewrite the law. I don’t believe he’ll be successful.”

At the same press conference, Cherokee Nation Attorney General Sara Hill said although the jurisdictional transition post-McGirt has had some flaws, the state’s depiction of legal chaos is “significantly overblown.” She also argued that increased tribal jurisdiction would, in fact, be better for public safety.

Hill also commented that the Cherokees, along with the Chickasaw Nation, are in favor of asking Congress to authorize the tribes to make agreements with the state over criminal jurisdiction.

“All roads in Oklahoma lead back to the state and the tribes really needing to find a forum to have discussions about how to resolve these issues,” she said.

The Biden administration has expressed opposition to the state’s claim of jurisdiction in Castro-Huerta, as have a number of tribes, native organizations, a group of former U.S. attorneys and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

Among those who have filed briefs in support of the state are the states of Texas, Kansas, Louisiana and Nebraska; the Oklahoma Farm Bureau, the Oklahoma Cattlemen’s Association and the Petroleum Alliance of Oklahoma; the Oklahoma Association of Chiefs of Police; and the City of Tulsa.

Castro-Huerta is just one of a number of cases the state has appealed to the the Supreme Court in recent months in an effort to limit the effects of the McGirt decision. Among the cases the Supreme Court declined to hear were a handful that dealt with the question of whether McGirt could be applied retroactively to cases in which a final conviction had already been handed down. The ruling of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, which said McGirt could not be retroactively applied in those cases, was allowed to stand.