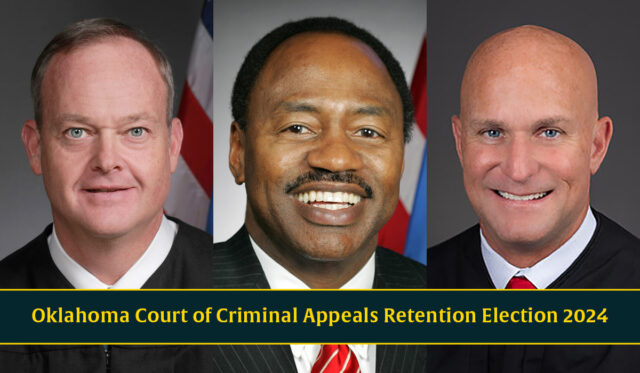

On Nov. 5, voters will decide whether to retain or unseat three judges on the five-member Oklahoma’s Court of Criminal Appeals: David Lewis, William Musseman and Scott Rowland.

Oklahoma is the only state besides Texas to have two “courts of last resort” — the highest court in a judicial system. While the Oklahoma Supreme Court can have the ultimate say in civil matters, the Court of Criminal Appeals has “exclusive appellate jurisdiction in criminal cases,” according to the state constitution. State statute tasks the court with the responsibility to review every death sentence.

RELATED

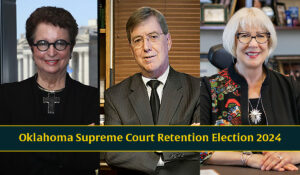

Supreme Court retention: PAC targets Yvonne Kauger, James Edmondson, Noma Gurich by Tristan Loveless

Judicial retention elections typically attract little attention. No judge has ever lost a retention election, nor do judges typically mount campaigns. Oklahoma’s Code of Judicial Conduct “imposes narrowly tailored restrictions upon the political and campaign activities of all judges” and explicitly forbids comment on specific upcoming cases or controversies the court expects to hear.

In preparation for the Nov. 5 elections, NonDoc sent questionnaires to all judges up for retention votes this year, including three Supreme Court justices and six judges on the Court of Civil Appeals. The questions sought answers within the bounds of the Code of Judicial Conduct, and Rowland discussed the limitations facing judicial retention candidates in his response.

“Appellate judges are prohibited by law and ethics from campaigning, soliciting votes, or even identifying themselves as belonging to any political party or organization, and it is therefore sometimes difficult for a voter to know how to evaluate those of us on the retention ballot,” Rowland wrote. “The judiciary is an entire, independent branch of government and citizens are entitled to judges of the highest quality and integrity. To ensure that such persons are appointed and kept, citizens should undertake whatever steps they reasonably can to determine which judges, in their opinion, fit that bill.”

The following article offers an overview of each Court of Criminal Appeals judge up for a vote, including when and by whom they were appointed, biographical information and quotes from their questionnaire responses. A PDF of the judges’ full responses to the questions can be found at the end of this article, and the Oklahoma Bar Association also has a website featuring information on all of the judges up for retention in 2024. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals maintains its own website, and its past decisions are available here.

To varying extents, all judges up for retention responded NonDoc’s questionnaire. The three Court of Criminal Appeals judges up for consideration Nov. 5 are presented below in alphabetical order.

David Lewis

Age: 66

Hometown: Ardmore

Law school: University of Oklahoma

The longest-tenured member up for retention on the Court of Criminal Appeals, Judge David Lewis was appointed to the court in 2005 by Gov. Brad Henry.

After graduating the OU College of Law in 1983, Lewis spent four years in private practice and four years as a Comanche County assistant district attorney before serving as a special judge in Comanche County from 1991 to 1999. He became a district judge for Comanche, Stephens, Jefferson and Cotton counties in 1999 and held that post until 2005, when he became the first Black judge in the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals’ history. In 2021, he was recognized as the longest-serving Black judge in the state’s history. He has previously served as the court’s presiding judge and vice-presiding judge.

Lewis sent a short statement in response to NonDoc’s questionnaire.

“I consider it an honor serving on the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals,” he wrote. “I enjoy the work, the people, and the dynamic of our Court. If retained by the voters, I will serve my term of office.”

William Musseman

Age: 52

Hometown: Tulsa

Law school: University of Oklahoma (1997)

Prior to his appointment by Gov. Kevin Stitt to the Court of Criminal Appeals in 2022, Judge William Musseman spent 11 years as a district judge in Oklahoma’s 14th judicial district, which covers Tulsa and Pawnee Counties.

“Those years of trial work allowed me to become well grounded in courtroom procedure and all other aspects of trial practice and the evidence code,” Musseman wrote in response to NonDoc’s questionnaire. “It is from that backdrop of experience which I now serve as an appellate judge on the Court of Criminal Appeals.”

Before serving as a district judge, he was a special judge in District 14. Prior to that, he worked in the Tulsa County District Attorney’s Office, first as an assistant district attorney and later as the director of the major crimes team. He was also designated as a special assistant United States attorney. This is the first time Musseman, who is currently the court’s vice presiding judge, has been up for retention.

“Ensuring a fair trial to both parties in our trial courts around the state is what motivates me to continue serving the most,” he wrote. “The opportunity to provide a fair and level playing field for opposing sides in court has been an amazing professional experience.”

A 1997 graduate of the OU College of Law, Musseman said the biggest issue facing the court involves “the magnitude of the decisions being made balanced with the public’s interest in the process.”

“Those decisions must be both correct and accepted by the public as reliable and trustworthy. To accomplish both parts, the judiciary must provide procedural and structural fairness,” Musseman wrote. “Procedural fairness assures parties a fair trial process and right to appeal through objective and neutral decisions. Structural fairness speaks to the integrity of those decisions as viewed through the lens of public perception. Judges must decide cases based on the law and rules of evidence without regard to personal belief.”

Musseman said judges “should give effect to the laws passed by the legislature and avoid implementing new laws from the bench.”

“To accomplish these objectives, I view my judicial role as restrained. To exercise judicial restraint, I believe appellate judges should answer the legal question presented in a way that gives finality to the parties and provides clarity for trial judges in future cases without expanding or shrinking the effect of laws passed by the legislature,” Musseman wrote. “I believe this philosophy of judicial restraint helps maintain both procedural and structural integrity, thereby upholding the public’s trust in the judicial system.”

Scott Rowland

Age: 59

Hometown: Wynnewood

Law school: Oklahoma City University (1994)

Judge Scott Rowland was appointed to the Court of Criminal Appeals by Gov. Mary Fallin in 2017, and he was named presiding judge in 2021. He graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 1987 with a double major in journalism and political science. Rowland began his career in law enforcement as a public information officer for the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics in 1989 and earned his juris doctorate in 1994 by attending the Oklahoma City University School of Law at night.

Before his appointment, he worked as an assistant attorney general for the state of Oklahoma, as general counsel to OBN and as first assistant district attorney in the Oklahoma County District Attorney’s Office.

“Prior to my now seven years on the bench, I spent almost thirty years learning, teaching, and practicing law,” Rowland wrote. “I handled hundreds of criminal cases in courtrooms throughout the State of Oklahoma. Those qualifications coupled with my natural love of public service allow me to approach this job with confidence, humility, and an understanding that every single one of the six hundred or so appeals we handle each year, from traffic tickets to death penalty cases, is the most important case in the world to the persons involved.”

Rowland said he believes the biggest issue facing Oklahoma’s judiciary involves earning and maintaining public trust in the courts.

“Judges are specifically required to behave in such a way as to promote and preserve that public confidence. I fear that, partly because of specific though isolated acts by some judges and partly because of general feelings of mistrust about government in general, some members of the public lack sufficient confidence in the judiciary and I regret that,” Rowland wrote. “The solution to this issue is for those of us in the judiciary to be above reproach both on and off the bench. We must understand that as judges we forego some of our basic rights, for instance the right to freely express opinions or engage in partisan political activities. We must accept that behavior or activities which might be tolerated in other lines of work are not acceptable in the judiciary if they tend to bring one iota of discredit or infamy to the bench.”