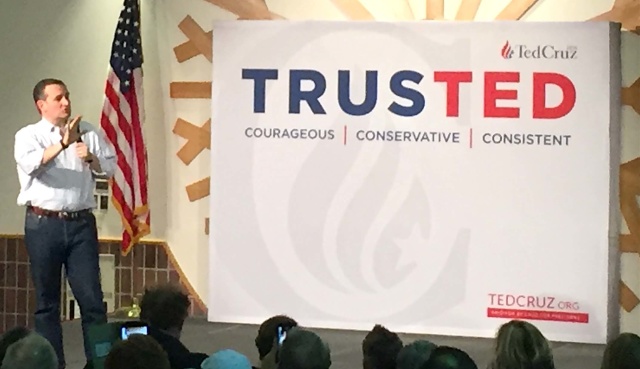

Early in the second week of January, just as questions about U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz’s eligibility for presidential office reached a fever pitch, Donald Trump’s campaign added a familiar song in political circles to its playlist.

Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band’s Born in the U.S.A., a song that gained political currency almost as soon as it was released in 1984, is now being used by the Trump campaign to troll Cruz for his birth in Calgary, Alberta, and his mother’s alleged Canadian voter registration.

Trump, who criticized Springsteen playing rallies for President Barack Obama’s re-election in 2012, has spent a good portion of his 2016 presidential campaign using recorded music as part of his messaging. But time and again, he has not asked the performers of those songs for permission to play their hits.

In the past seven months, Trump has incurred the ire of Neil Young for his campaign’s use of Rockin’ in the Free World, and received similar cease-and-desist requests from artists for playing R.E.M.’s It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine) and Aerosmith’s Dream On. In December, Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider rethought his previously announced support for Trump’s use of We’re Not Gonna Take It when the presidential hopeful came out in support of banning Muslims from entering the United States.

From a legal standpoint, Trump is mostly in the clear. In a Rolling Stone interview from June 2015, Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski said they had cut checks both to the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) and to Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI) to cover such public presentations. According to the ASCAP website, most major venues purchase blanket licenses for the public use of music. Additionally, national campaigns generally purchase their own blanket licenses so that they can stop in at a town square or a business and still hit play on their Spotify lists of message songs.

Trump is not alone on this. In November, Frankie Sullivan, the principal songwriter for the band Survivor, filed suit against Republican presidential hopeful Mike Huckabee for copyright infringement when his campaign played Survivor’s Eye of the Tiger during Kentucky County Clerk Kim Davis’ release from jail.

“There’s a two-stage process involved here,” said Tyler Johnson, associate professor of political science at the University of Oklahoma. “You can license the music through ASCAP, but if a campaign is smart and they want to use it in the long run, they won’t just license it, they’ll also get permission from the artist, especially if you’re going to use it in a prominent space.”

Most campaigns will only take the first step, since few of these cases move beyond a complaint in the press or social media, much less a cease-and-desist letter, Johnson said. In addition, media reports on such incidents tend to be washed, rinsed, dried and put away within one 24-hour news cycle.

“So I started thinking about this in terms of Russian Roulette,” Johnson said. “Will the link between the song and your campaign become prominent enough for the artist to know it is taking place, and will they care?”

Recent history is filled with cases of politicians and artists clashing over the use of recordings, but most observers agree the most famous first case involved Born in the U.S.A when it was invoked by President Ronald Reagan during his 1984 re-election campaign.

“America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside our hearts,” Reagan said during a 1984 campaign stop in New Jersey. “It rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire: New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”

Born in the U.S.A. is not exactly a clarion call of positivity about the American Dream — it resolutely tells the story of one man ground down by American Reality — but it sounds hopeful and patriotic when politicians forget to listen to the words. Springsteen spoke about Reagan’s words a few days later at a concert, wondering aloud if Reagan had actually listened to the song.

After Springsteen, the list is voluminous. In 2012, Silversun Pickups issued a cease-and-desist order to the Mitt Romney campaign for using Panic Switch. U.S. Sen. John McCain got dinged for using Jackson Browne’s Running On Empty, and once Sarah Palin joined his campaign, the Republican candidates received a litany of cease-and-desists from Heart, Foo Fighters and Van Halen, among others.

And in one of the most pugnacious battles over the use of a song, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker began using Dropkick Murphys’ I’m Shipping Out to Boston at campaign stops in his now-ceased 2016 presidential campaign. Dropkick Murphys self-identify as a pro-union band, and yet one of the country’s best-known union-busting officials was using their song. This was essentially a textbook case of “false endorsement” under the Lanham Act, which protects performers and celebrities against improper use of their likeness or work in such cases.

@ScottWalker @GovWalker please stop using our music in any way…we literally hate you !!! Love, Dropkick Murphys

— Dropkick Murphys (@DropkickMurphys) January 25, 2015

The band, however, never pursued legal action.

It’s important to note there are also instances where Democrats have been served with cease-and-desist letters: Sam Moore of the classic R&B duo Sam & Dave asked Barack Obama’s campaign to stop using Hold On (I’m Comin’) in 2008.

“As a political consultant, I always looked for a piece of music that set the tenor for the campaign, that would energize people and, at the same time, make them think and maybe pull at the heartstrings a little,” said Michael Carrier, a former strategist who now serves as director of communications and outreach for OU’s Julian P. Kanter Political Commercial Archive. “In the past 25, 30 years, these campaign theme songs have become increasingly important as identifiers. They’re critical in giving a campaign life. They are usually the first and last things you hear at a rally.”

That element to creating a feeling of identification and allegiance at a campaign stop, it turns out, is not easy to obtain.

“Truth is, most campaigns don’t ask permission. They just grab them,” Carrier said. “My opinion is that they don’t ask because they don’t want to be turned down.”

Both Carrier and Johnson agree the situation is unlikely to change unless more performers like Frankie Sullivan of Survivor agree to push their cases legally. Carrier said it could take a class action lawsuit to change the status quo.

“It could take that, and it might take someone with the reach and wealth of Bruce Springsteen to lead it,” he said. “Or maybe the record companies could file suit. The use of popular music in campaigns is probably going to explode at the court level in the next 10 years, and judgments against campaigns could run into the six figures. It will be the easiest money some of these artists ever made.”