With Sayre Memorial Hospital closing Feb. 1 and Craig General Hospital in Vinita filing for bankruptcy in February 2015, Oklahoma Hospital Association president Craig Jones has many concerns.

“I hate to call it a crisis, but clearly we are in some very serious times as health care transitions,” Jones said.

In interviews, Jones has a tendency to hunker down in the weeds of health care policy, and a 29-page PDF on the OHA website — called Transforming Health Care: A Proposal for Oklahoma’s Future — is replete with convoluted graphs, arrows, circles, bullet points and icons.

But the long and short of the OHA’s positions is that Jones and his board believe Oklahoma should accept federal funding to expand Insure Oklahoma (in a manner similar to Arkansas’s Medicaid-expansion alternative) and that rural hospitals need to be proactive in considering what scopes and models they may have to focus on moving forward.

“Oklahoma chose not to expand the traditional Medicaid program, and we as an association have been on a campaign for the last couple of years trying to use the federal dollars that are available to expand the coverage under Insure Oklahoma,” Jones said. “There are a few other hospitals that are evaluating whether or not they can maintain inpatient services, which tend to be more costly.”

So far, Jones’ “campaign” to increase insurance coverage among Oklahomans — and thus potential hospital reimbursements on patients currently uninsured — has been unsuccessful. As a result, hospital administrators are concerned.

“It’s a huge negative impact because we lost a big chunk of payment to pay for the ACA, and then when we didn’t get the expansion of Medicaid and the additional payment for those (uninsured patients), we got hurt on both ends,” said Grady Memorial Hospital CEO Warren Spellman. “It could be a death blow.”

CNHI reported last week that the shuttering of Sayre Memorial Hospital in western Oklahoma marks the nation’s 67th rural hospital to close its doors since 2010.

The Tulsa World reported in 2015 that seven rural Oklahoma hospitals have filed for bankruptcy over the same time span: Drumright, Fairfax, Pauls Valley, Prague, Seiling, Stigler and Vinita.

Jones said the financial pressures that rural hospitals face are great, exacerbated by a lack of reimbursement for uninsured patients who would be covered under Medicaid expansion or an Insure Oklahoma-expansion alternative.

“What the Legislature and others don’t realize is: These patients are not going away,” Jones said. “If we don’t expand Medicaid — if we don’t expand coverage under Insure Oklahoma — these same patients are showing up in your emergency department.”

Stronger surveys put hospitals on heels

In the meantime, Oklahoma hospitals have been facing a different challenge: inspections for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that have become more regular and more stringent in their safety assessments.

“What’s happened over the last three years, there’s been a huge increase in actual survey activity,” said Lee Martin, service director for medical facilities with the Oklahoma State Department of Health. “In 2012, some hospitals were being surveyed every five to six years, now they’re being surveyed maybe every three to four years.

“There was a big effort and push at the state health department.”

That push appears to have stemmed from pressure by CMS, according to people NonDoc talked to for this report. The OSDH contracts with CMS to conduct the federal agency’s surveys, and Martin admits that before he assumed his position four years ago, the agency wasn’t meeting its federal guidelines.

“There was a lot of turnover with the nurses and stuff,” Martin said. “Hospitals weren’t being surveyed in the (proper) time frame.”

Now, Jones and hospital administrators are finding out just how strong properly conducted CMS surveys can be. But an increase in violations requiring quick remediation — called immediate jeopardies — has Jones and others wondering if the surveyors have become too harsh.

“What we began to see was a change in how the health department personnel were going about conducting these surveys,” Jones said. “I’m not trying to be overly critical of the health department, but I think they themselves found that the performance of the surveying process was not up to par.”

Since Martin took charge of OSDH’s surveying, Jones said hospitals in Vinita, Wagoner, Poteau, Chickasha and elsewhere have been tagged with survey violations that have disrupted operations. Hospital CEOs with Wagoner Community Hospital and Craig General Hospital (in Vinita) did not return phone calls seeking comment.

RELATED

Grady Memorial CEO on proposed tax: ‘I have no choice’ by William W. Savage III

“What was difficult for the hospitals is that they may have had one or two other surveys in the past, and in their opinion nothing really has changed in terms of their current conditions, but suddenly there are deficits being found,” Jones said. “In other words, they may have had an area pass in the past, and suddenly the same area isn’t passing now.”

Jones attributed that change to two things: First, he said OSDH is being stronger in its enforcement of complex rules. (The state operations manual is 149 pages long, not including numerous appendixes.) Second, he said some health care providers have not kept themselves “up to speed” with changes in federal codes and regulations.

“I will say that my staff has spent numerous hours helping and facilitating people to do a correct plan of correction,” Martin said. “In 2012, when I first took this position, people were really struggling to do an acceptable plan of correction.”

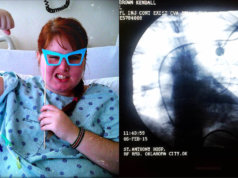

CMS requires plans of correction for hospitals where issues are found, but as Spellman (the Grady Memorial CEO) found out, a 19-day window for remediation of an immediate jeopardy violation is often too short to begin improvements.

Spellman had to close his hospital’s surgery center in fall 2015 to avoid losing all CMS reimbursements. He and the hospital’s public trust proposed a sales tax on Grady County residents to fix the hospital, which passed with 80 percent of the vote this month.

“I believe other hospitals have suffered in silence because they don’t want to poke the bear,” Spellman said of stringent safety surveys. “They don’t want to make the state mad.”