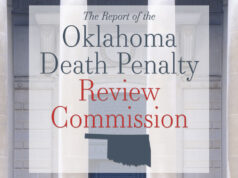

Support for the death penalty in America’s most conservative corners has been crumbling as of late. The Nebraska Legislature voted overwhelmingly to repeal capital punishment. The Utah State Senate approved a measure to end its use, but full repeal was only stymied because their legislative session ended.

The signs of a turning tide are also starting to surface in Oklahoma. Recently, polling showed that a plurality of Oklahoma Republican voters were open to replacing the death penalty with an alternative, and, in light of recent events, that is an understandable sentiment. The national spotlight has focused on Oklahoma following embarrassing botched executions, a subsequent ongoing grand jury investigation, and repeated attempts to execute a man despite a lack of physical evidence — Richard Glossip.

Botched executions halt capital punishment

Early last year, Oklahoma executed Charles Warner, but not everything went as expected. An open-records request revealed that the state had administered the wrong drug. Rather than injecting Warner with the approved lethal-injection combination, he was given a dose of a chemical normally used to treat icy airport runways. As disconcerting as this was, it wasn’t Oklahoma’s first botched attempt. In 2014, Clayton Lockett’s execution went so poorly that in the midst of the execution, officials hastily halted the process, and Lockett later died of a heart attack.

Executions have since been placed on hold as a multi-county grand jury has been tasked with investigating Oklahoma’s lethal-injection drug debacle. Their findings are expected to be released soon, but, considering that three senior officials connected to the episode have recently resigned, the malfeasance must run deep. Regardless of the grand jury’s conclusions, Oklahoma is expected to resume executions, which imperils Richard Glossip.

The case of Richard Glossip

Glossip gained national notoriety because he was the plaintiff in a highly anticipated US Supreme Court decision regarding execution methods, but he is also known for nearly being executed three times despite a dearth of physical evidence. In 1997, Barry Van Treese, the owner of the motel where Glossip worked, was brutally murdered. Within days, one of Glossip’s employees, Justin Sneed, was apprehended by law enforcement officials, and he promptly confessed to killing Van Treese. Sneed had a documented history of criminal activity and drug use, and upon his admission of guilt, the case should have been closed. However, Sneed’s interrogators pressured him to identify Glossip as the crime’s mastermind. Glossip had no prior record of felony violence, and there was zero physical evidence linking him to the crime. Nevertheless, under intense pressure from the police, Sneed claimed that Glossip asked him to murder Van Treese in exchange for compensation. Consequently, Sneed received a sentence of life without parole, and Glossip was found guilty and condemned to die.

If nothing else, Glossip’s case exemplifies how easy it can be to receive a death sentence even with an astonishing paucity of evidence. In fact, the prosecution’s case against Glossip centered on circumstantial evidence and Sneed’s highly questionable testimony, which has changed no fewer than eight times. Last year, as Glossip’s execution loomed, his pro bono defense team discovered three witnesses who came forward to cast serious doubt on Sneed’s allegations. Considering that Sneed’s suspicious testimony is the only evidence linking Glossip to the murder, his case certainly merits another look.

A cautionary tale

Glossip’s case should serve as a cautionary tale, but unfortunately it isn’t the exception. Questionable and even wrongful convictions have indelibly marred the death penalty program. Nationally, 156 individuals have been wrongly sentenced to die, and 10 have been released from Oklahoma’s death row because of erroneous convictions. This is, in part, why conservative icons like Jay Sekulow, Dr. Ron Paul and Richard Viguerie have been outspoken supporters of repealing capital punishment. The stakes are simply too high — and our faith in the government too low — to continue supporting the death penalty. Given that capital punishment costs far more than life without parole, doesn’t keep the public safer, and can prolong the legal process for murder victims’ families, it really is a failed government program — just the kind the conservatives despise.