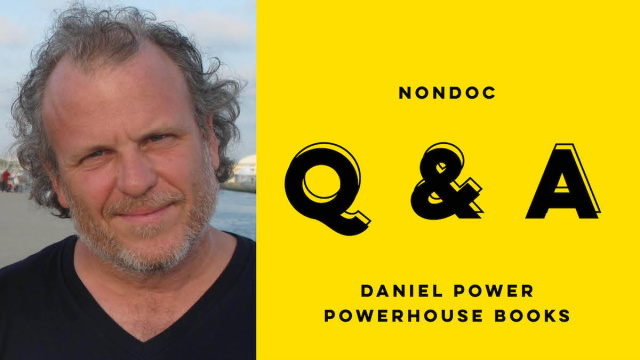

It isn’t often that the publisher of an art book becomes the target of a copyright-infringement lawsuit, but that’s exactly where Daniel Power found himself recently.

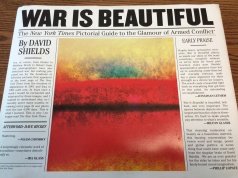

Power, who founded powerHouse Books in 1995, published David Shields’ War Is Beautiful last year. The book’s use of photographs from the paper’s front pages sparked a lawsuit from the New York Times, even though the publisher licensed those images directly from the photographers.

Here, Power responds via email to questions about the NYT’s ongoing legal action against his company, fair use in book publishing versus online publishing, and the real value of the art book in question.

Responses have been edited lightly for style and grammar, and the interview has been shortened.

Are you a regular reader of the New York Times? How does this shape your opinion of the paper?

I don’t read the paper, but I do read articles I come across on news aggregators. I think their reporting is fine (politics, etc.), but this ridiculous suit makes me realize the office and management side of it is run by arrogant clowns.

How does a small publisher gear up for something like this? Can you afford the legal battle? What’s the cost? What is lost in the effort?

You don’t. You just stick to your guns even when your own lawyers are saying, “Wow, it’s so much cheaper to just pay them off.”

But I never [expected] my photo book business (I’m pretty [much] the last independent one of my size left in the U.S.) to make money; I wanted to bring important visual stories in book form to the marketplace and, with any luck, pay some bills. So if it’s not right, there is no extent to which I will not go to make it right and just.

They’re bullies — I call them that because all they want to do at this point is cause financial pain: They changed their claims three times already (first threat was we needed to change the subtitle and the cover, then just the subtitle on our website and on Amazon, and when we said no and they realized they didn’t have a case, they seized in the endpapers and their tiny reproduction as a copyright claim; now they are claiming it’s not a copyright issue, it’s just a collection issue).

And it’s still not right, but it is costing a lot to prove this point. But I will not back down, they don’t deserve to receive income off this book that is a critique of their photo-editing methods, and the author David Shields is entirely within his right to show the headlines of the paper editions in question for the images he chose. One of his tenets in this book is that the NYT photo-editing process subtly supports and undergirds U.S. military policy and initiatives during engagements from 9/11 to now.

What’s the case about?

The latest is that they’ve pivoted from a copyright infringement suit to a “simple collections” case after reading the withering critiques of their weak case, from Rebecca Tushnet to TechDirt to many others (in fact, in a letter to Judge Sullivan, they claim that we “launched a PR campaign to appear as some free expression crusader” due to the fair-use blogs that tore apart their position).

Before they filed the suit, they sent an invoice for some $19,000, claiming this was due in total for each of the tiny front pages reproduced on the back endpaper. They might even appear to be trying to claim that if they had been placed in the interior of the book that this might be fair use, but since they are on the endpaper, which is technically function and can be decorative, we’re using their [intellectual property] to decorate inside of our book and they are entitled to income from that. They don’t realize that we use the endpapers for editorial information, too, and it’s going to be interesting when I enlighten them about editorial photographic aesthetics in books of our ilk.

We assume and even insist on a high level of intelligence when comprehending all that our titles have to offer in way of content, design and purpose. You can access them on very base levels or, if you put some work into it, you can see and understand more complex interplays at work. These endpapers are a coda if you will of the [entirety] of the book’s tenets, making full sense only after viewing and reading the full interior of the book. It’s like a macro view [of] what’s in essence 112 detailed studies.

Keep in mind that we fully licensed the images in the interior from each copyright holder, including the NYT’s own staff photographers. So each of the 64 small thumbnails contains a main image that has been licensed, and the text on these tiny thumbnails [is] illegible. The only thing that is legible is the headline and the masthead.

To your knowledge, how does (or should) the First Amendment protect a book like this?

Fair-use standards commonly accepted allow for reasonable amounts of excerpts and citation. Ditto music. However, book publishers have been scared to death of reproducing even the smallest amount of copyrighted visual material without permission. Whereas bloggers can write and post images at will without fear of reprisal (falls under news), books, even serious critiques like this, are considered “commercial products.”

While you can’t show, say, a Pepsi can in a Hollywood film without permission and probably fee payment, what about a documentary, educational and/or newsworthy in nature? Books should be the same.

So in this regard, as one of the critiques of the suit online pointed out, this suit could be an interesting case in opening that use up for visual-use makers. We publishers should be able to reproduce, in partial and/or supportive format, advancing a larger theme in the book, something without seeking permission and/or forced to pay exorbitant fees.

You purchased the photos from the Times. To my (growing) knowledge, fair use generally entails that if you are making a teaching or journalistic statement, then you are fine with using content. But you also purchased the pictures, so that covers you, too. Did you and editors, partners or the writer get together to discuss the risk of the project? Were you surprised when NYT filed a suit?

I think you mean, “Why did we license the images when we were OK to use them in first place (without asking or paying)?”

Two reasons: While we were clear to reproduce the front pages, according to Shields’ advisors, that would have led to a boring, repetitive book: each page looking the same, and the text taking away from the singular focus on the content of the image itself. As you read in Dave Hickey’s excellent essay at the back of this book, there is a lot of pre-editing and composing by the photographer as the shot is set up or captured. His point is that the editing-selection process has led to a self-censoring by photographers who deliberately go out and look for that Times front-page shot, as opposed to really documenting the horrors and vicissitudes of war, what war photojournalism was like in the ’60s.

Secondly, we’re a photo book publisher. We’ve done a lot of photojournalism books, and we are known for high-quality reproductions and printing; we make our books look nice and do the best possible job we can producing faithfully an artist’s work. And few know as well as I do how hard it is to make a living as a photojournalist, and how hard the photo agencies representing them work to find places willing to pay to use them. So it’s really only fair to license the images properly, and in the process get the high-res files we’d need to do them justice and reproduce them in a manner that is faithful to the photographer’s work and easy for the reader to view and appreciate.

Were the end-of-book thumbnails of the full front pages licensed?

No.

Although the book seems pretty deep and allusive, the NYT says there’s no “transformative” purpose to the project. What could they mean by that?

Initially it meant they thought we were trading on their name; they thought the subtitle “The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict” was literal. We were like, “Are you f–king kidding me?” I guess the article in the subtitle not being italicized went over their heads. So we added an asterisk, “*In Which The Author Explains Why He No Longer Reads The New York Times.”

That said, I have no idea how someone could digest this book and come away thinking we’re just ripping off their name and likeness and stealing their IP. The book is a pretty cutting critique of the methods and process of the photo editing by the Times, and how it magically dovetails with U.S. policy and objectives of the time, and how there was an amazing precedence during the second world war, when this paper may have or did underreport atrocities against Jews, which mirrored U.S. efforts to define war as one against tyranny, not one of stopping genocide. So no, it escapes [me] how they can claim it’s not transformative at all.

In your mind, what is valuable about War is Beautiful?

People question motives in reading an article or a piece of text yet look at an image and believe the point of the image is transparent, pure, and all of the behind-the-scenes work — photo selection, cropping, placement, even captions (we even provided original photographer copy in addition to the Times’ captions to show how the Times’ changed it!) — is not considered or factored into questioning what the image means and why it’s here on the front page of my paper.

So this book, for the first time I think, outlines what might be going on before the photographer even sends work back to the editor’s desk (seen in the Hickey essay), and the Shields intro outlines how this paper has operated in the past as a surrogate explainer of military initiatives and policy, and that the selection of the images here, along with the dates and front pages [in which] they appeared, can be viewed in a way that shows the paper is indeed still that surrogate.