(Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of stories about an ongoing land dispute between the Wichita, Caddo and Delaware nations in western Oklahoma.)

ANADARKO — A cemetery on top of a hill here holds the remains of children who died while attending the Riverside Indian School.

Below the hill is a 71-acre parcel where the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes operate a convenience store and travel center. Nearby, they are building a 4,000-square-foot museum to tell their people’s story.

Meanwhile, the Caddo Nation is going to court over the land, alleging additional remains may be buried there and claiming the Wichita don’t even own the property.

The Caddo filed a lawsuit May 25 seeking to halt construction for two weeks while the tribe conducted archeological work with ground-penetrating radar, or GPR, which can identify potential artifacts or features without the need to disturb a site by digging.

A U.S. District Court judge ordered a temporary stop to work at the site, one and a-half miles north of Anadarko, pending a hearing. The order was lifted May 31, and the Wichita resumed work. The Caddo then filed an appeal on June 7 to the 10th U.S. Circuit Court in Denver. No hearing date has been set at this time.

Burial records lost in fire

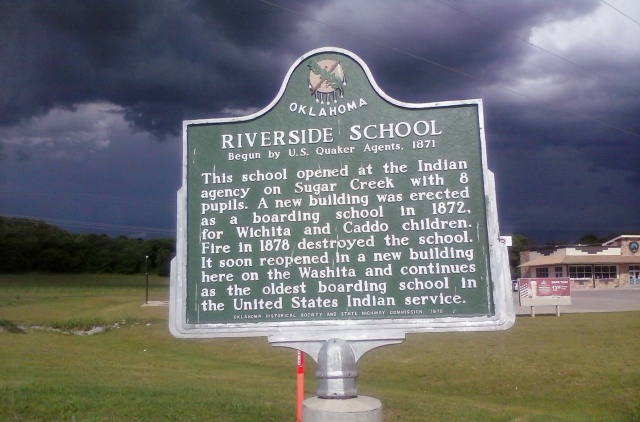

Riverside Indian School remains the Bureau of Indian Education’s oldest operating school. It was opened in 1871 next to what was then the Wichita Agency a mile north of the Washita River.

Most of the early students were Caddo. Later, students from the other two tribes sharing their reservation, the Wichita and the Delaware, would join them. Eventually, students would attend from the Kiowa, Comanche and Apache reservation south of the Washita River, as well as students from other tribes across the country.

The first student to die at the school and be buried there was a girl named Nellie Block. According to a history of the school written by a former teacher, she died in June 1872 and was buried “on top of the hill behind the agent’s residence.”

It’s hard to say exactly where the other students who died there over the years are buried. A fire destroyed many of the school’s early records, so even if there were maps of the burials, they were probably lost at that time.

‘They need to shut it down’

As far as Shirley Davilla knows, all the graves are supposed to be on top of the hill. Davilla is a member of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes executive committee and one of the defendants named in the Caddo lawsuit. She attended Riverside as a child and grew up in Anadarko. She has served on various boards and committees for the Wichita since 1976.

She said that in all that time she had never heard about burials so near the building site.

“That’s what’s strange about it,” Davilla said. “Nothing was ever brought up about any graves being there or anything.”

Delaware Nation President Kerry Holton said there isn’t just one cemetery.

“There’s a lot of cemeteries,” Holton said, adding that bodies buried in one place may not stay there. “Everything comes off of that hill.”

Holton said he has seen archeological reports showing funerary objects in the field below the hill where the cemetery is reported to be.

“They need to shut it down and stop it completely,” Holton said of the Wichitas’ development.

Wichitas claim due diligence done

In a statement, Wichita President Terri Parton said her tribe has complied with every federal rule — and then some. The Wichita commissioned a study by an independent archaeologist who issued a report April 6, 2015. The report noted the land where the Wichita sought to build the history center included a known archeological site potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. More work would need to be done at the site to see if significant artifacts were lying beneath the surface, the report states; however, the Wichita decided not to fund further research.

“To protect what history may lie under the site, the Wichita Tribe followed federal guidelines and paid to have extensive archeological studies performed of the area, all of which concluded that construction on the site of the Wichita History Center would not disturb any sensitive or historical objects,” Parton’s statement said.

A judge agreed, ruling the Wichita complied with all of the procedural requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act, a 1969 federal law that calls for builders involved in certain kinds of projects conduct an environmental assessment prior to beginning work, and the National Historic Preservation Act, which requires consultation with affected tribes if a site may have religious or cultural significance.

The Wichita began working on plans to develop the site in 2008. The travel plaza, which occupies the 71-acre parcel’s south end, was completed in 2013.

Parton stated one archeological survey of the site had already been conducted, but the Wichita funded a second after partition of the land to ensure there would be no significant impact to either the environment or sites of cultural importance. A third survey was then conducted before breaking ground on the history center site “to ensure that the construction was undertaken with the utmost integrity.”

Caddos denied access to reports

Caddo Chairwoman Tamara Francis-Fourkiller said she would like to see those archaeological reports.

“We’ve been asking for them for months now,” she said.

Francis-Fourkiller formerly served as Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Delaware Nation, consulting with government agencies and private builders to ensure construction would not adversely affect artifacts and sites of historical value.

Prior Caddo leaders were notified of the plans the Wichita had to build at the site and did not get involved, but that was before Francis-Fourkiller became chairwoman. She said the people who occupied the office before her just didn’t know any better.

“Not everybody has that background,” Francis-Fourkiller said. “They don’t understand certain things that come across their desk should not be approved.”

According to their court filings, Caddo elders have spoken of burials on the lower lands either on or near the construction site. “Years ago, Caddo remains were moved from the lower lands to higher land near the ‘Kiowa Cemetery’ up the hill,” the filings state.

Owing to a cultural prohibition against touching the remains, non-natives were called in to handle them.

The Caddo stated in court that one of the people involved in the reburials has since come forward to confirm the story.

“Caddo Nation officials are concerned that other Caddo graves were not moved and continue to be located in the construction area,” a statement filed by the Caddo said.

Contingency plan creates tenuous peace

The Wichita have a plan in the event unexpected artifacts or human remains are found during construction. In that event, work would stop and a 200-foot “avoidance zone” would be set up around the location of found items. Notice would then be sent to the other tribes.

Parton said Francis-Fourkiller is asking the Wichita to “effectively surrender control of the museum project to the Caddo.”

Francis-Fourkiller said she doesn’t want to control the project. She just wants the Wichita to build their museum somewhere else.

“Nothing needs to be built on that site,” she said.