Friday, Hillary Clinton’s doctor reportedly diagnosed the 2016 presidential candidate with pneumonia.

The diagnosis was not made public until Sunday afternoon when she left New York City’s annual 9/11 ceremony early and stumbled while getting into a van. Clinton campaign staff initially said she was overheated and suffering from exhaustion, but hours later they announced her pneumonia diagnosis.

Event highlights health speculation

In short, the Democratic presidential nominee is sick, as further evidenced by a politically awkward coughing attack she endured at a Labor Day rally.

But rampant speculation by random YouTubers (mostly on the political right) asks whether Clinton has a worse condition than the pneumonia that has been reported. Some have used a blurry photo of a Clinton handler’s hand to speculate further and often irresponsibly.

At the moment, however, the best information available to the public does not contradict Clinton’s announced diagnosis of pneumonia. The New York Times went long on the issue Sunday, noting that neither Clinton nor the GOP nominee have released extensive health records.

In an effort to provide the public with fair medical information about pneumonia, NonDoc offers the following write-up from new co-owner Dr. Ashiq Zaman.

With the first 2016 presidential debate scheduled in two weeks on Sept. 26, this information is intended to answer questions about pneumonia in general and Clinton’s potential recovery timetable, but it is not intended to provide analysis of Hillary Clinton’s specific health or diagnosis.

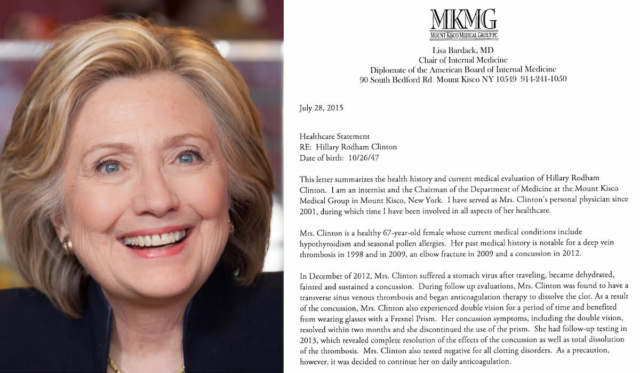

Her campaign’s 2015 health care statement is embedded at the end of this post.

— William W. Savage III

An overview of pneumonia

Alveoli are the tiny air-sacs in our lungs that facilitate the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide with each breath we take. Pneumonia is a condition affecting these air-sacs, causing them to fill with fluid or mucous. It is most commonly caused by bacterial or viral pathogens but may also be associated with inflammation from environmental exposures or autoimmune conditions (non-infectious pneumonitis).

Community-acquired pneumonia is relatively common and is usually caused by pathogenic bacteria or viruses. Bacterial pneumonias tend to encompass the more severe presentations of the disease and may require hospitalization

About 1 million people are hospitalized annually in the United State for pneumonia, according to the CDC.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of pneumonia starts with the clinical presentation. Moderate-to-severe cough, sputum production, chest pain, fever above 100 degrees Fahrenheit and malaise are common symptoms. A chest X-ray can provide more definitive evidence of fluid in the lungs if the clinical picture is unclear. In severe cases of bacterial (or fungal) pneumonia, a culture of the sputum may be done to isolate and identify the causative organism to direct appropriate therapy.

Treatment of pneumonia depends on the cause. For viral pneumonia, treatment is generally supportive, consisting of rest, Tylenol or NSAIDs like ibuprofen and fluids. Antibiotics, though often prescribed, do not treat viral conditions and may worsen antibiotic resistance in the community.

Bacterial pneumonias are a different story. Mild bacterial pneumonias in otherwise healthy individuals can be treated with a short course of oral antibiotics, in addition to the supportive measures mentioned above. Hospitalization and IV antibiotic therapy is generally reserved for treatment-refractory cases or for patients who have other risk factors including age (the young and the elderly), history of cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, history of smoking or any kind of immunodeficiency, including HIV/AIDS.

(In the New York Times’ piece referenced above, Clinton’s physician, Dr. Lisa R. Bardack, is quoted as saying her patient “was put on antibiotics, and advised to rest and modify her schedule.”)

Prognosis

Prognosis, like presentation and treatment, depends on the causative agent and associated risk factors.

For otherwise healthy individuals, bacterial community-acquired pneumonia typically improves after a week or so of supportive measures and antibiotics.

However, in at-risk populations, pneumonia is a potentially dangerous condition and, unfortunately, remains a common cause of morbidity and mortality. The CDC notes that 50,000 Americans die of pneumonia each year, while nearly 1 million children under the age of 5 die globally.

What can you do to reduce your risk?

See your doctor if you are having symptoms, particularly if you have high fever or are coughing with sputum production. Quit smoking or avoid second-hand smoke. Stay on top of your risk factors and make sure any predisposing conditions are followed closely and managed by your physician.

— Dr. Ashiq Zaman

Hillary Clinton’s 2015 health care statement