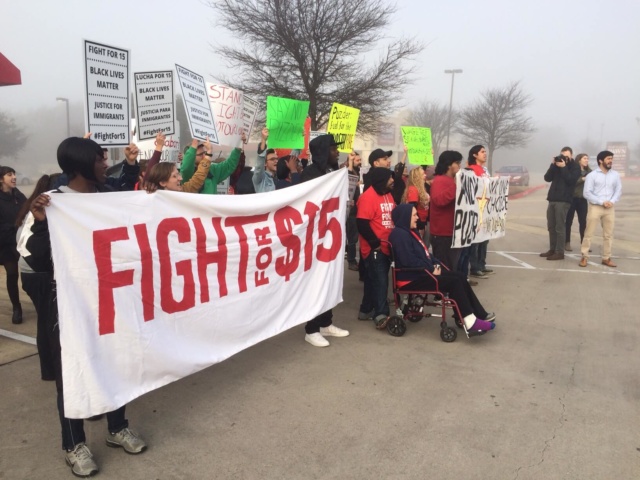

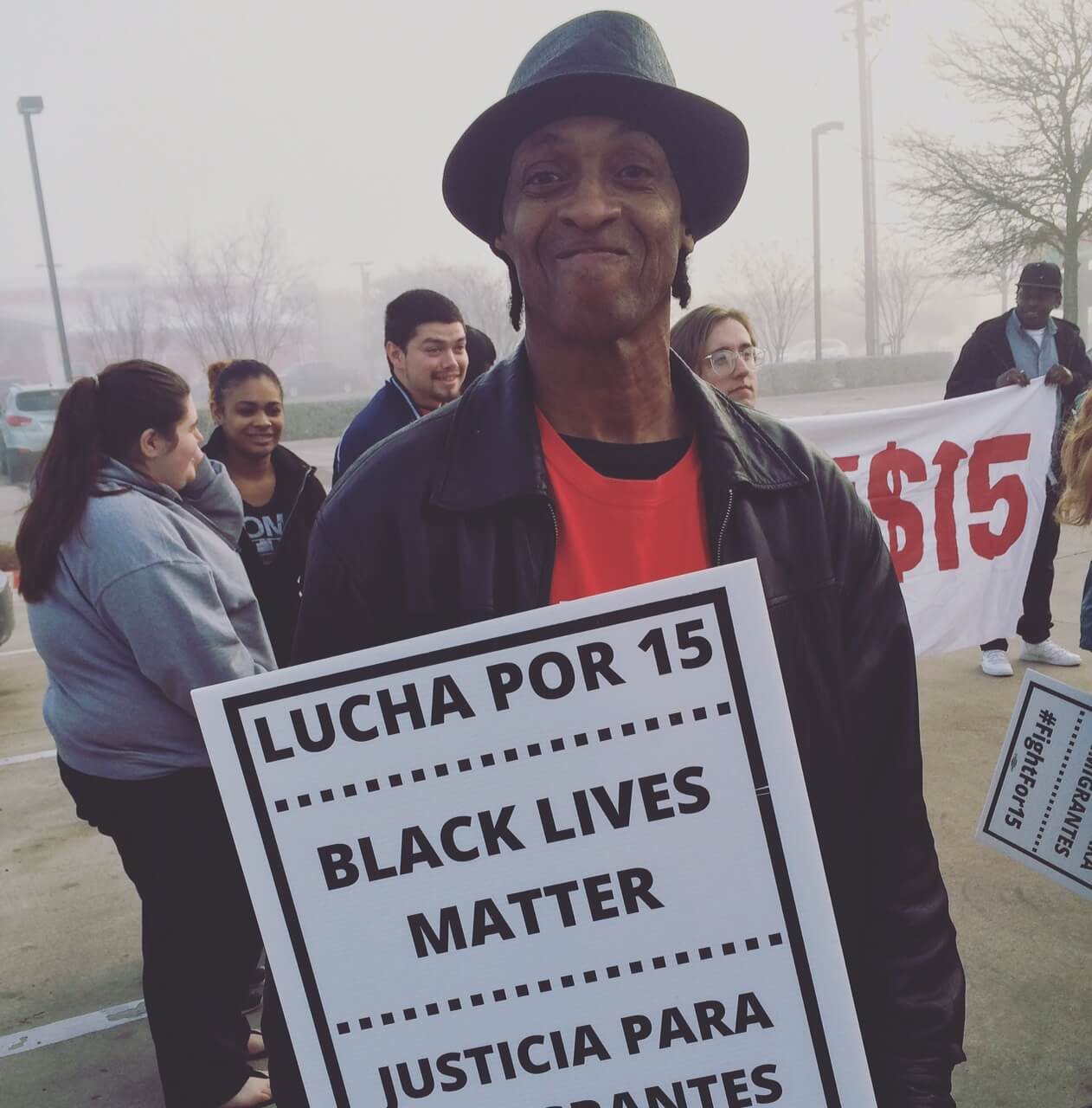

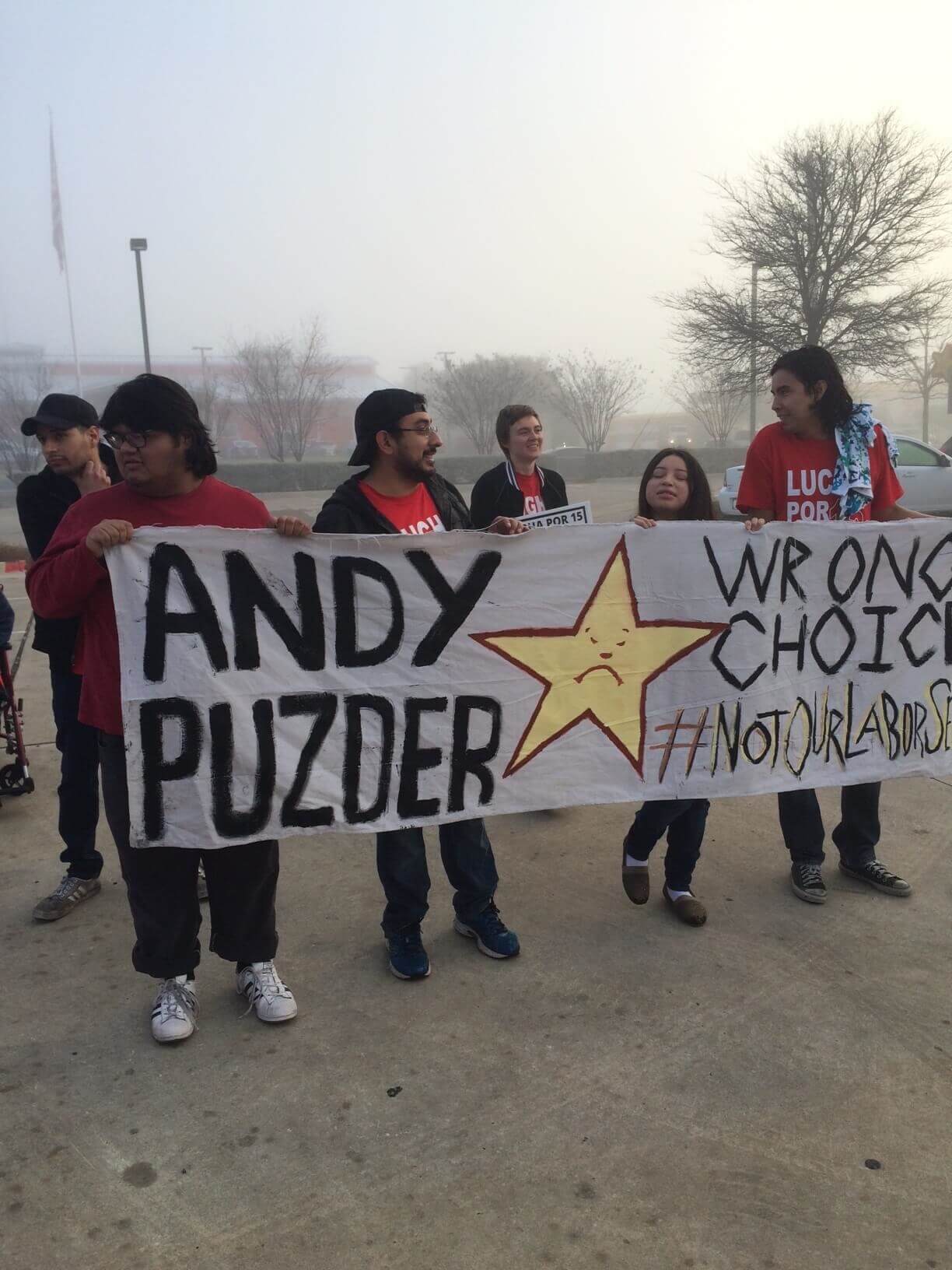

AUSTIN — At 8 a.m. on the morning of President Donald Trump’s inauguration, a group of protesters set up camp outside of a Carl’s Jr. on Slaughter Lane. It was the beginning of a long day of protests nationwide, this one demanding a minimum wage hike in defiance of Trump’s proposed pick for labor secretary, Andy Puzder, a critic of unions, a minimum wage skeptic and the CEO of CKE, Carl’s Jr.’s parent company.

The morning of an unknowable administration shrouded the south Texas palms in a mist. The smell of French Toast Dips hung heavy in the air, as protesters chanted.

“When workers rights are under attack, what do we do? Stand up, fight back.”

“We want change, and we don’t mean pennies.”

The mix of fast-food workers and young-ish activists switched up a variety of rallying cries, leading the group through the drive-thru two times before stopping on the north side of the restaurant to listen to speakers. Later, the crowd picked up a riff based on Denzel Washington’s Remember the Titans:

“We are the workers, the mighty, mighty workers …”

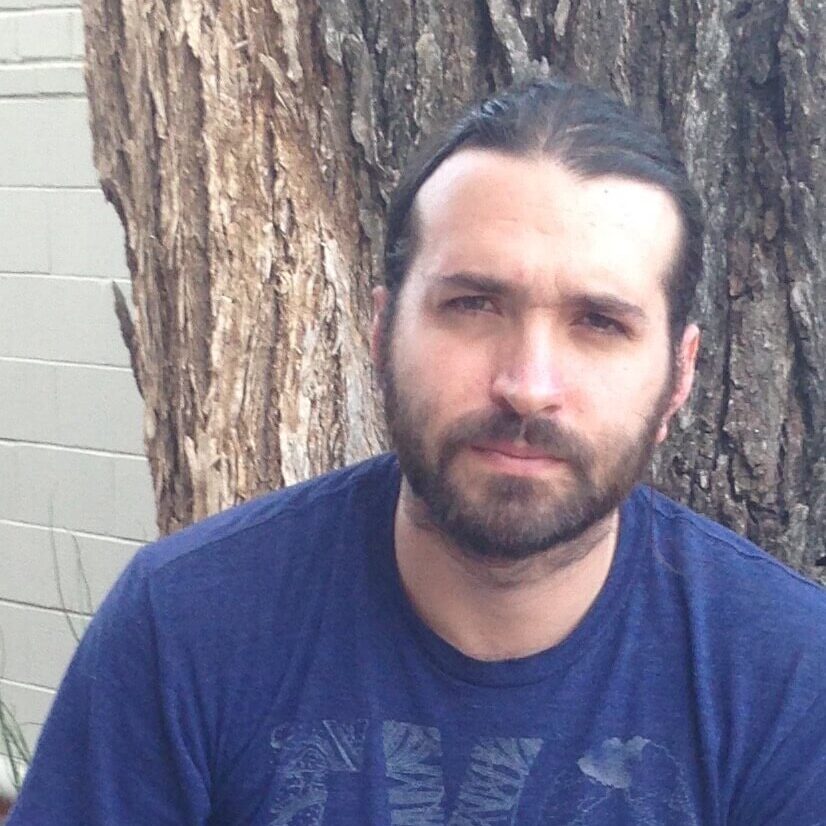

Organizer Brad Crowder introduced Joshua Perez as a Wendy’s employee who had grown as a leader with the Fight for 15 group.

Perez talked about his and his co-workers’ fight to get an air-conditioner fixed that led to a one-day strike at a San Marcos Wendy’s. The store’s air conditioner had long been a problem, but the strike came after a manager suffered a stroke in the 109-degree heat.

After the Wendy’s shut down for a day, the vice president of the franchise agreed to fix the situation, later telling employees that the strike caused them to halt other renovation projects, Perez said after the rally.

That prompted Perez (who has 100 university hours down, works 42 hours a week and sometimes gives plasma) to look up the VP’s previous earnings at Disney on LinkedIn.

“He was getting paid around $300,000 a year, so he doesn’t know about struggle,” Perez said.

Perez told the audience about Puzder’s comments in favor of automated machines to replace workers if needed and “sexist antics” in reference to a bikini-clad Carl’s Jr. ad of some repute.

Fight for 15 seeks a living wage

The New Yorker at first declared the Fight for 15 movement quixotic and then startlingly effective in its four years of effort. Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles have all approved a $15 minimum wage.

Where fast-food workers had typically been excluded from wage debates on account of high turnover, the Fight for 15 activism that began with 200 walkouts in 2012 eventually brought ballot initiatives last year that will increase Arizona’s minimum wage to $12 by 2020; Colorado to $12 by 2020; Maine to $12 by 2020; and Flagstaff, Arizona, to $15 by 2021.

The nation’s highest minimum wages are in the state of Washington: $15.35 in SeaTac and $15 in Seattle, according to CNN.

Texas has a state law that keeps minimum wage at the federal minimum ($7.25) and prohibits cities from raising it. Oklahoma has a similar law.

But Austin District 4 City Councilman Greg Casar said the council has made efforts to improve payment where possible. They’ve also passed the Fair Hiring Ordinance, which protects applicants with criminal histories in the hiring process. It applies to all private businesses as well.

In lieu of a 2014 Obama executive order raising the minimum wage on federal contracting jobs to $10.10, the Austin City Council required contractors and subcontractors who work with the city to pay a living wage by raising the wages of city employees, temps and temporary employees toward $13.50 an hour currently, Casar said.

“For example, somebody that’s working at the airport, or somebody that’s landscaping the right of way here, anybody that’s working, not just as a city employee, but also doing work for the city, even in the private industry, we can apply those living wages through contracts,” Casar said. “Because that’s our right to contract, and it’s raising the minimum wage on co-workers who work in a private business, but part of doing business with the city.”

Of note, while the Department of Labor can’t enact a wage increase or decrease, it can advise the president on policy such as this, and it can penalize employers who short their workers on pay.

ProPublica notes that labor advocates are concerned Puzder “could roll back a new regulation, currently held up in court, that would expand eligibility for overtime pay.”

Puzder wrote a manifesto titled Job Creation: How It Really Works and Why Government Doesn’t Understand It. For Puzder, the key to successful business is to keep labor costs down.

“Less federal programs, reduced deficit spending, lower taxes, and cutting back on regulations improve The Certainty Factor,” Puzder wrote.

Meanwhile, a New Yorker brief on Fight for 15 suggests, “we have no real idea whether they will also make businesses less likely to hire new workers or keep the ones they have. A sizable body of economic research suggests that minimum-wage hikes do not have a significant impact on employment.”

‘I have no time to cook’

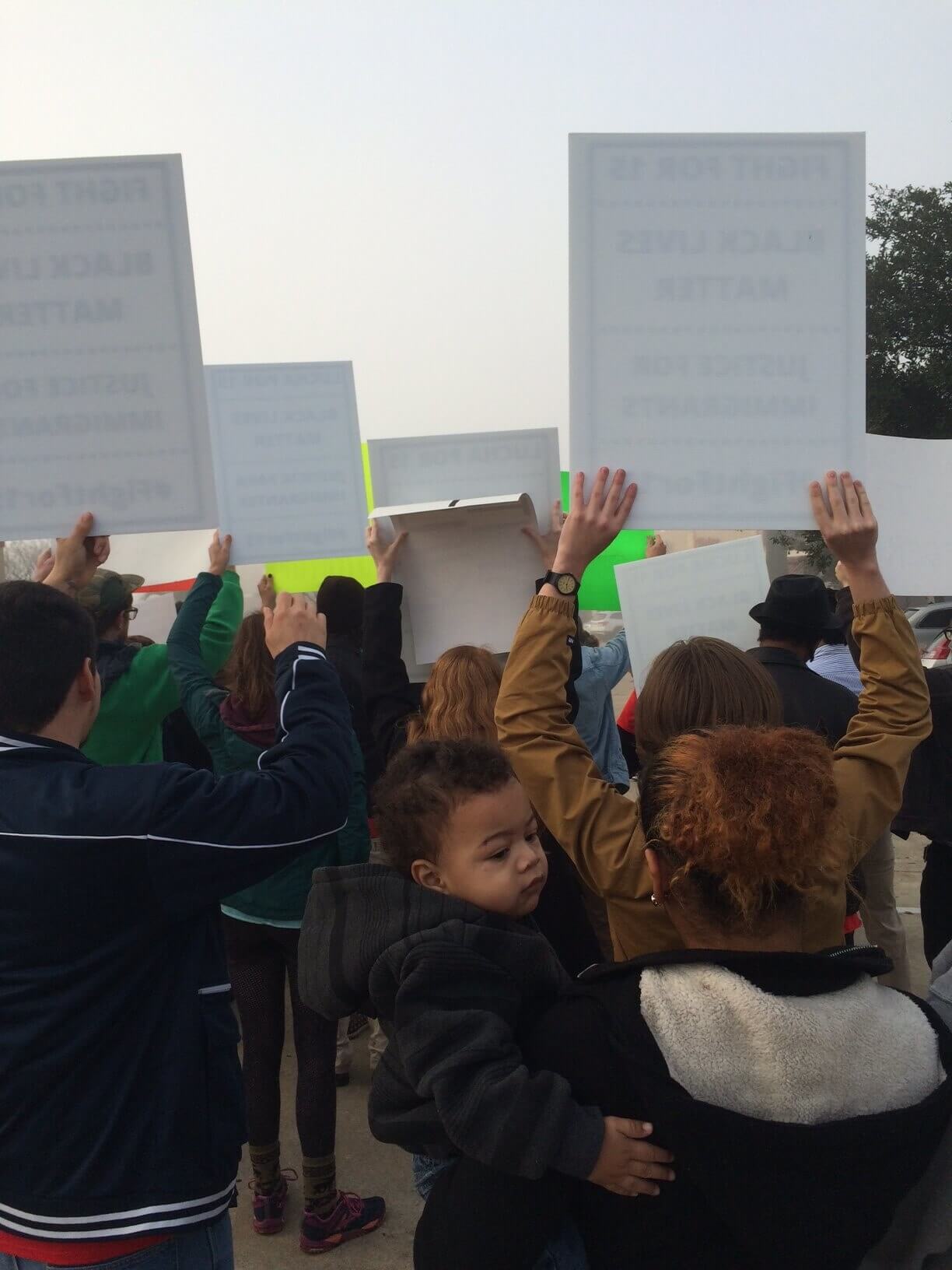

As Friday’s assembled group inched closer to the busy Slaughter Lane, a green car passed with mother and daughter honking in approval, and the window clerk served a breakfast seeker with a slightly annoyed gaze.

For some workers, it was their first demonstration.

“I’d rather get paid $15 than $9,” said Brittney Luna, whose interest was piqued when a Fight for 15 recruiter talked to her outside of her job at Church’s — her other 30 hours of work done at McDonald’s.

When I ask her how she’s doing and how she’s eating, her friend, Katilynn King (a Jack in the Box worker), interjected.

“She’s always at work,” King said. “She ain’t got time to do nothing else. Work in the morning, then goes and works at night at the other job.”

Luna explained further.

“As of now, I eat at my job,” Luna said. “I have no time to cook. This is actually new to me. My first time out.”

King, who works 40 hours weekly, held her son Jeremiah during the protest.

“I got kids, so I gotta do what I gotta do,” King said. “Once you get it to $15, price of living is just going to go up higher. So it’s going to have to keep going up and going up. When my momma was working, they made like pennies, and now the price of living is going to keep going up.”

Luna said her paycheck is stretched thin.

“I just moved into a new apartment for now,” she said. “I heard like the cheapest place down here is Killeen. It’s a small little town, but that’s the cheapest you can get. Me and my boyfriend were living with his mom, kind of thing. We’re 21 now, so it’s like, we gotta move out.”

Daniella Vasquez works with Perez at Wendy’s. A mother, she had a job she really liked at a rehabilitation hospital. She was a receptionist there with other women. Little by little, her supervisors cut her hours until she was barely on the schedule.

“So I went with location because Wendy’s was right down the street, and [there is] availability for my daughter for a sitter, and it’s just working out,” Vasquez said. “It’s cut pay, you know, but it’s a sacrifice that I’m going to have to deal with for a while. Which I’m willing. I’m dealing with it right now.”

Perez and Vasquez retain their Wendy’s jobs while protesting without trouble (though higher-ranking employees would not be able to protest).

“They are little bit salty because I don’t come at night. I mean I’m supposed to be there tonight,” she said.

Vasquez, who also spoke to the crowd Friday, said she feels she joined Fight for 15 at the right time in her life.

“I don’t have family or parents to say ‘here you go’ or ‘let me do this.’ No, it’s all on my own,” she said. “It’s tough, but I still manage to do it. Ever since the last meeting, I just feel more motivated to come to work to be a part of this — to be more involved.”