House Bill 1482 has caused quite a stir at the Oklahoma State Capitol since it passed a House committee 11-1 on Feb. 15. Numerous people have approached NonDoc to discuss the legislation, some in praise, though most in opposition.

The bill has drawn criticism from state mental health advocates and others who favor reforming a criminal justice system that incarcerates an outrageous number of young people, women and minorities.

They say Oklahoma voters just passed State Questions 780 and 781 to slow the state’s school-to-prison pipeline, and they see HB 1482 as a response from irritated Oklahoma district attorneys whose coffers could continue to receive more money from fines and probation agreements if they can charge (and jail) drug offenders with felonies rather than misdemeanors.

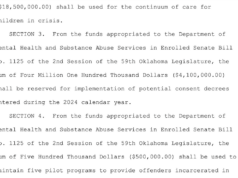

HB 1482 has been titled the “Keep Oklahoma Children Safe from Illegal Drugs Act of 2017,” which might be the most manipulative and misleading name for a bill so far this session. The bill (embedded below) would make simple drug possession a felony within a 1,000-foot radius of an extensive list of properties:

… a day care, public or private elementary or secondary school, public vocational school, public or private college or university, or other institution of higher education, church, recreation center or public park, including state parks, fairgrounds and recreation areas.

The bill would also make possession “in the presence of” a child 12 or younger a felony.

Boring is fascinating

NewsOK’s Jaclyn Cosgrove published a lengthy story Sunday on the conflict between State Question 780 and HB 1482. It’s a balanced must-read to understand the political positions of Oklahoma DAs and Oklahoma advocates for criminal justice reform.

Let’s unpack some of the arguments being made within:

Mike Boring, district attorney for Beaver, Cimarron, Harper and Texas counties, is among a group of district attorneys concerned about the impact that State Question 780 will have on drug courts.

Boring said because simple drug possession is no longer a felony, prosecutors no longer have a way to motivate people to choose drug court.

“Check the people in drug court right now — people in drug court are not there because they want to be in drug court,” said Boring, who has served as a district attorney for 14 years. “They’re there because it’s the only alternative to going to prison for 10 or 15 years, and they know if they don’t stay in drug court, they’re going to end up going to prison.”

Boring doesn’t have drug courts in his counties, and his only option for drug treatment is to force people to pay for their own treatment from a private provider.

Boring’s hypocrisy is — pardon the wordplay — fascinating. How can a district attorney argue that he needs leverage to send people to drug court when, in fact, he has no drug courts to which he can send offenders in his jurisdiction?

While prosecutors with drug court access certainly could threaten the felony docket as leverage over addicts, Oklahoma District Attorneys Council members Mike Fields, Kevin Buchanan, David Prater, Greg Mashburn and (update your website, guys) Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter are certainly smart enough to know there’s more than one way to skin a cat.

Moreover, the idea that Oklahoma’s leading prosecutorial minds would say, “Gee whiz, we can’t figure out any other way to encourage professional help for an addict whose life is in the shitter,” is about as believable as the dumb excuses those same prosecutors often hear from offenders.

But dumb excuses are also at the heart of Boring’s support for HB 1482, filed by Rep. Scott Biggs (R-Chickasha).

In the NewsOK article, Boring ignores the fact that possession with intent to distribute — and plain distribution — charges are still felonies. Instead, he and the proposed legislation argue that even students possessing drugs at or near a school or university need to face the threat of felony charges and prison time.

Also, 17- and 18-year-old students caught with drugs at school need to know they’re facing serious charges, and many of them will laugh off a misdemeanor, Boring said.

“Understand, we’re not putting those kids in prison on the first offense,” Boring said. “The deal is to get their attention.”

In contrast, former GOP House speaker and current chairman of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform Kris Steele told NewsOK that HB 1482 would do more harm than good for at-risk, drug-using youth.

“For the young person who may be in a school and experimenting with drugs, which unfortunately happens, the worst thing that we can do in that situation is label that young person as a felon for life,” Steele said. “Research indicates that when we label a young person … as a felon for life, it is more likely to drive that young person deeper into the criminal justice system.”

Steele said that House Bill 1482 was a “creative way to make simple possession a felony offense again in the state of Oklahoma.”

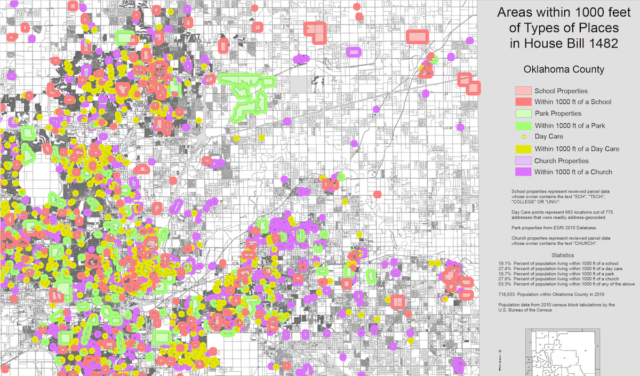

Under House Bill 1482, 53 percent of Oklahoma County lives in a felony drug possession zone — when all places in the bill’s 1000-feet zone are considered, according to the Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform.

That last statistic should actually appear even more jarring if you consider how most of the unaffected areas of Oklahoma County lie in its rural corners.

Disingenuous arguments could be downfall

As HB 1482 prepares for a potential floor hearing this week or next, lawmakers will have to balance their political fears of voting against a “tough on drugs” bill while recognizing the reality of how incarcerating young people for drug possession does virtually nothing to help them address their problems.

Should the public — which voted to pass State Questions 780 and 781 by sizable margins — recognize the disingenuous nature of the aforementioned pro-HB 1482 arguments, perhaps Oklahoma district attorneys will have to compromise on this legislation or, at least, make a more honest go of it.

If these highly trained lawyers choose to feign incompetence by claiming they can’t do their jobs unless drug possession is once again a felony, maybe voters will kick them out of office in deference to attorneys who don’t whine so much.