At the beginning of this year, NonDoc contributor and former Oklahoma Gov. David Walters authored a commentary about the need for a Balance Sheet Commission. His premise was that such a commission could be formed “for Oklahoma to monetize unproductive assets.”

In a way, such a commission already exists. The Office of Management and Enterprise Services’ Division of Capital Assets Management (DCAM) has a Real Estate and Leasing Services unit, known as REALS.

Think of it like the state’s rummage sale. There are all kinds of state-owned properties languishing in disrepair and underuse. Holding onto these properties loses the state money in two ways: 1) There are costs to maintain them (if even minimally); and 2) Since the state owns them, these properties generate no revenue from property tax. On the other hand, selling the properties offers two benefits, the first in one-time revenue from the transaction and a second in recurring revenue from annual property taxes.

Last week, DCAM administrator Dan Ross reported to the House Government Modernization Committee (GMC) that more than $3.1 million in revenue had been generated thanks to the sale of more than 362,000 square feet of underused state-owned and leased properties. The bulk of those funds went toward the renovation of roofs for three Department of Corrections facilities.

As Walters pointed out in his January post, there’s almost a billion dollars to be made in the sale of state-owned properties. For example, the Grand River Dam Authority utility plant is worth almost $600 million, according to financial statements from 2015. Likewise, the 9,000-acre MidAmerica Industrial Park, worth about $200 million near Pryor, Oklahoma, could be considered ripe for sale, at least according to Walters.

Rummage sale could benefit troubled bridges

As the need for new recurring revenue becomes more dire, money generated from the REALS program could go to a long line of state needs, including Oklahoma’s bridges.

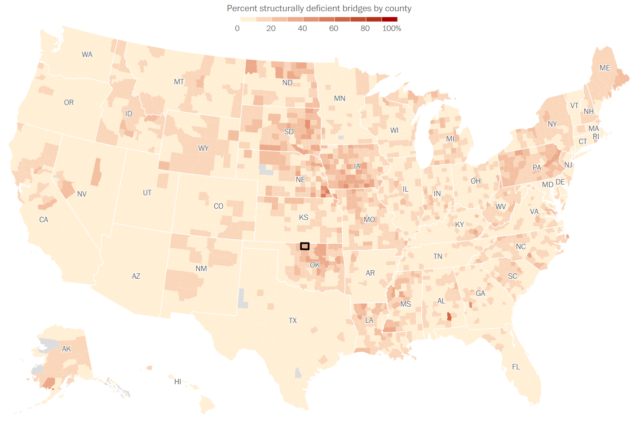

A 2016 report from the American Road and Transportation Builders Association showed Oklahoma as having the third-most number of “structurally deficient” bridges in the country for the year of 2015 (latest data available).

For a county-level perspective, check out this nifty interactive tool from The Washington Post, which pulls from the National Bridge Inventory database. According to it, 10 percent of Oklahoma County’s bridges are considered “structurally deficient,” which is slightly higher than the national average of 9.4 percent. In Kansas-bordering Grant County, however, structural deficiencies plague almost 40 percent of bridges.

Bureaucracy poses a hurdle

While the Legislature debates how to address Oklahoma’s budget problems, keep in mind that a common-sense approach to government that sounds good on paper usually fails to take into account the many hidden and competing interests of the politicians and lobbyists actually pulling the strings.

As Walters wrote in his piece’s conclusion, “… if the state wants to put together monetary resources to create a huge fund to support education, it will be complicated, politically difficult and controversial … but possible.”

As an example of those politically difficult complications, consider that the eight-member House GMC oversees 10 subcommittees with the aim of creating economic efficiencies in sectors ranging from transportation to education and IT security.

So regardless of what’s possible, the realistic perspective must focus on what’s probable. For creating those forecasts, we can rely only on past performance.