A&E has aired a show called Live PD since October 2016. In it, viewers watch live as camera crews follow multiple police departments around the country in real time. Legal commentator and former Nightline anchor Dan Abrams hosts the show with the subtle uncertainty of a weatherman trying to pinpoint the most likely areas of danger in a developing storm. (Just like with weather coverage, however, the danger sought rarely unfolds.) Two former Dallas police detectives also provide commentary from a desk à la SportsCenter.

Basically, Live PD is Cops meets the Internet’s live-streaming capabilities meets the broadcast of a sporting event, and it’s a damn shame.

Presenting the socio-cultural disconnect and disintegration of trust between largely urban communities and local law enforcement benefits no one and should not be presented as entertainment.

Criticisms for ‘Cops’ apply to Live PD, go deeper

The same criticisms viewers have for the long-running Cops ride-along show can also be leveled at Live PD. In 2013, the same year the phrase “black lives matter” appeared following the verdict in the Trayvon Martin shooting case, self-described racial justice group Color Of Change urged Fox to cancel Cops, citing the false narrative the show creates:

Although marketed as unbiased, Cops actually offers a highly filtered version of crime and the criminal justice system — a ‘reality’ where the police are always competent, crime-solving heroes and where the bad boys always get caught.

Later that same year, Fox actually did cancel Cops, but male-centric cable network Spike picked it back up.

Ironically, news and opinion blog Mediaite, which Abrams launched in 2009 and still owns, had scathing criticism for Cops in 2013, with then-contributor and now-Daily Beast senior editor Andrew Kirell writing, “… the show’s legacy is one of glorifying and overlooking abuse through a highly-selective, heavily-edited depiction of ‘reality’,” and, “… COPS’ turning of serious matters into cheap entertainment has often been coupled with the willful neglect of serious issues like police misconduct and civil rights.”

Kirell also quotes former Los Angeles PD deputy chief Stephen Downing, who criticized officer behavior on Cops:

[T]hey show officers violating the Fourth Amendment routinely, manhandling people, not employing the escalation/de-escalation concepts of the use of force.

Live PD cheapens serious matters further by airing footage as it happens. In that sense, the law enforcement officers (LEOs), camera crews, studio crews and viewers all wind up edging toward conflict.

For the LEOs, the camera crew’s presence heightens their need to follow procedure while confoundingly creating the added pressure of delivering action for the viewers. Meanwhile, the producers know that “if it bleeds, it leads,” to borrow a newsroom dictum, so they’re actively directing the live coverage to locales with the highest danger factor. Farcically, Abrams and his commentary crew must highlight and allude to the potential dangers of situations that fizzle instead of flare up. Last, as viewers, we lose interest if an episode repeatedly features false alarms and low-level busts, so even subconsciously we seek to witness bad things happening to people we have the luxury of regarding as “getting what they deserve.”

So as Live PD’s hours of content unfold during Friday and Saturday nights (on A&E, of all stations), the entertainment cheapens far below Cops, with all parties involved hoping for the equivalent of a NASCAR crash.

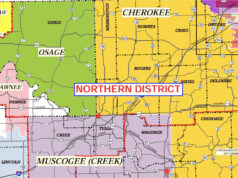

Tulsa PD dips in, out of Live PD

Much of Live PD’s first season followed Tulsa PD’s gang unit. Led by the practically made-for-TV Sgt. Sean “Sticks” Larkin, TPD’s contributions illustrate the double-edged sword of a live ride-along show.

Larkin and his partners know their usual suspects by name, and the suspects often call Sticks by his nickname. He’s obviously developed a rapport with local gang members, which is positive for the city to highlight. In episode two, he actually lets some gang-affiliated men off the hook despite finding them smoking weed and having outstanding warrants.

At the same time, a confrontation Sticks initiated with a man in episode one drew widespread criticism on social media:

Regardless of the later revelation that the man in blue had been arrested more than 50 times, apparent unprovoked harassment of a black man otherwise minding his business created a bad look for what seems like an otherwise effective task force.

TPD apparently agreed: When A&E announced in February it would be extending the debut season from eight to 21 episodes due to ratings growth, TPD bowed out.

“We just didn’t like the way it represented Tulsa and the police department,” The Frontier reported TPD chief Chuck Jordan as saying.

“I’m not a fan of a TV show that is trying to feed off the difficulties [our] police officers face,” Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum was quoted in the same story.

‘Police work is not entertainment’

In the Feb. 1 press release regarding the season-one extension, A&E head of programming Elaine Frontain Bryant stated:

By presenting an unfiltered look at how our country is being policed and prompting the thought-provoking conversation that follows, we’ve tapped into the cultural zeitgeist in a way that no other show has before.

The network has “tapped into” something alright, but it seeks not the supplemental purpose of, say, a lightning rod tapping into atmospheric charges to divert them safely. Instead, A&E’s Live PD resembles more the parasitic ends of a mosquito.

To return to the previous criticisms of Cops that still apply to Live PD, Patrick Camden, with the Chicago Police Department, responded thusly to a request for Cops to embed its crews in the Windy City in 2005: “… police work is not entertainment. What they do trivializes policing. We’ve never seriously even considered taping.”

Camden is correct: Police work is not trivial. Would one seek to trivialize it, however, few methods would be more effective than inserting camera crews in cop cars across the country and airing their daily operations and interactions live. Top it off with attempts to provide color commentary and analysis as if reporting on a football game, and America inches one step closer to making The Running Man a reality:

Still not convinced? Just ask the family of Benjamin Johnson, whose mother arrived at home in January to find camera crews airing live the scene at which her 36-year-old son had just been shot and killed after a drug deal gone bad. Johnson’s relatives happened to be watching as cameras beamed images of his lifeless body into their (and, literally, about a million other) homes.

In perhaps a telling turn of events regarding local law enforcement’s motivations in that South Carolinian community, the county sheriff has refused to apologize to the family or change its policies regarding Live PD’s ride-alongs.

Live PD: Made possible by viewers like you

Regardless of the “thought-provoking conversations” Live PD’s “unfiltered look” claims to offer, the fact remains these shows trivialize the very real nature of hard-working LEOs and troubled communities they seek to serve.

To jump around from bust to bust across the nation removes the context of incarceration policies that leave youth with broken families; of historically located and generationally poor neighborhoods a larger white society had pushed them into and has kept there; of underfunded school systems that can’t pay enough teachers enough money to stay; of a society that would rather lock nonviolent drug offenders up for profit instead of offering treatment.

We don’t have enough information to make a judgement on Live PD’s suspects or police as people, and we don’t learn the outcomes of the ensuing charges and verdicts. As such, their portrayal in these shows occurs in a vacuum and serves to reinforce negative stereotypes about minorities and people with mental health issues.

So if these ride-along shows have so many detriments, why do they continue to thrive?

Because of us. Cops has aired for 29 seasons. Live PD averages 1.1 million viewers weekly. If you search #LivePD on Twitter, you’ll find nary a criticism of the show but plenty of calls for expanded coverage — say, a live-streaming 24-hour web feed, for example.

With demand like this, Live PD may be just the beginning in a new era of hyper-reality TV. While the networks, their parent companies and shareholders will likely benefit, few others will.