If you haven’t been paying attention, the Oklahoma Legislature is back in session and headed for its homestretch. Look at all the cowboy hats.

The governor, the attorney general and the “education” guy are in place and doing their respective things. Here, one may say, we are going again.

Throw in negotiations with sovereign tribal nations, and we’re guaranteed snits, spats and to-dos aplenty. Sometimes I feel sorry for my son, who covers the Capitol every week and writes some sort of newsletter, among other things.

Of course, if the Oklahoma Legislature looks like chaos — well, that’s how our state got started at the turn of the last century.

A microcosm of our initial population?

First, when America furthered its frontier West into more and more Indigenous territory, the area had land runs. Chaos on the hoof. Then, the white folks started calling for statehood. Eleven years passed before there were enough people living here for the place to qualify.

Republicans were in control in Washington, and their feet dragged on the question of statehood because they feared Oklahoma would be a Democratic stronghold, and they wanted time to build Republican power here, via political appointments and whatnot.

So, we were tools before we were tools.

Anyhow, along came the Oklahoma Enabling Act of June 16, 1906, which wrote the recipe to be followed in the creation of a new state.

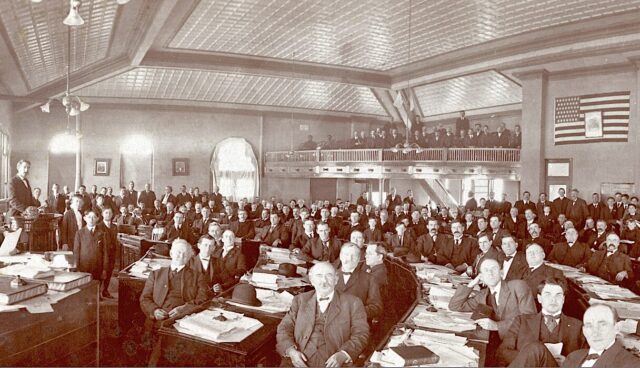

The so-called Twin Territories — Oklahoma and Indian — were to be joined, and each would send 55 delegates (plus two from the Osage Nation) to a constitutional convention in Guthrie, a Republican outpost that was, according to the Enabling Act, to be the state’s capital until at least 1913.

The convention first met on Nov. 20, 1906. Of the 112 delegates, 100 were Democrats, and that was it for Republicans until the first coming of Henry Bellmon.

About the delegates, we know this: Their average age was 43. Among them stood 47 farmers, 27 lawyers, 12 businessmen, six preachers, three teachers, two physicians and one student. Besides them, the wag would say, 14 other people with no visible means of support also attended.

Was that a microcosm of our initial population? Hard to say. I am told even fewer lawyers and physicians serve in the Legislature now, but the teacher and preacher numbers have climbed.

Populist fear of centralized power

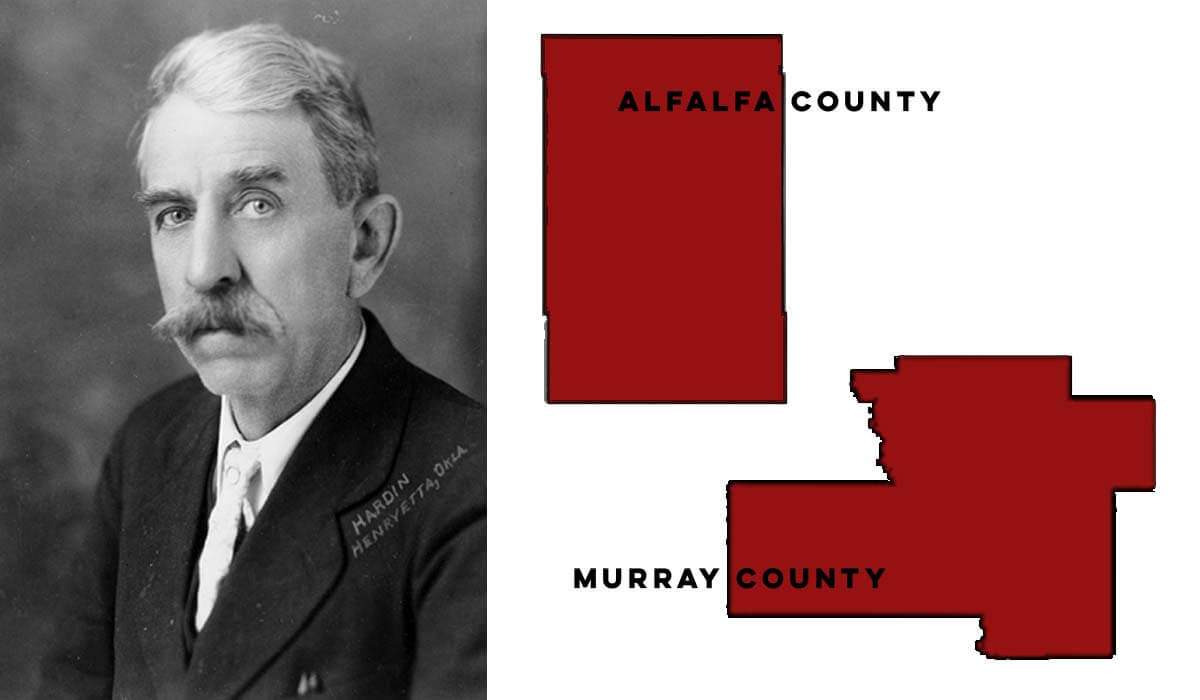

The president of the 1906 constitutional convention was none other than that soon-to-be nationally known bigot, crackpot and whatnot named William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray.

RELATED

History is clear: Alfalfa Bill Murray was a terrible bigot by William W. Savage Jr.

He began the proceedings by having the delegates join together in singing Nearer, My God to Thee, the hymn that would be played six years later on the deck of the sinking Titanic.

Perhaps Murray had a premonition, and not about a big boat.

The convention produced a 45,000-word constitution that President Theodore Roosevelt hated because Democrats had written it, but no legal reason existed for rejecting it because the document followed the stipulations of the Enabling Act to the letter. (I forbear particulars, except to note that in Oklahoma you cannot have more than one spouse at a time. Having them serially is another matter, but the Legislature works on that, from time to time.)

The Oklahoma Constitution was praised for its populist and progressive content, with many provisions limiting centralized control and empowering the Legislature as the institution most responsive to the will of the people.

Scholars wrote about it, but nit-pickers were not silent, complaining that the document was too detailed. Good grief, the thing even specified the flash point of kerosene, a provision designed to prevent corporate greed error that could result in towns burning to the ground if it were cut with cheaper fuels. Such atrocity had happened elsewhere.

A constitutional convention redo? Be careful what you wish

From time to time, the electorate is invited to help remove outdated parts of the Oklahoma Constitution.

I recall the election in which the section requiring state payments to widows of Civil War veterans was excised. Someone had noticed that, on account of the passage of time, there were no such widows left.

Over the decades, voters have been asked to decide several questions related to the Oklahoma Constitution, which has been amended more than 200 times. In recent years, we have voted on liquor laws (twice), marijuana laws (twice, to different results), the separation of church and state, expanding Medicaid coverage, modifying school funding options, and whether to elect the governor and lieutenant governor jointly.

The results have hardly painted a straight ideological line.

I learned recently that Cherokee Nation citizens will be asked this June whether to call their own convention for revision of the tribe’s constitution. Various Oklahoma political factions sometimes float the idea of a new state constitutional convention as well.

If the state were to have a new constitutional convention, every moron in America with something to suggest would show up and try to participate, just as Carry Nation lobbied the original convention to prohibit consumption of alcohol. Ultimately, Gov. Charles Haskell successfully pushed the proposal as a separate article to be approved months later, and prohibition continued in Oklahoma for a quarter of a century after the rest of the country had reversed course.

By that measure, our path to Medicaid expansion felt relatively quick. Nonetheless, calling a new constitutional convention in Oklahoma would revive the recipe for chaos, to be sure. These days, 45,000 words would hardly do it.

In the meantime, perhaps the best we can hope for is legislators whose mothers taught them it’s impolite to wear your cowboy hat in the House — or the Senate.