When Tara Hood and a group of dedicated parents decided to advocate for the Oklahoma Legislature to pass a bill mandating health insurance coverage of autism treatment, she thought it would take a few years.

“We didn’t know what we were doing,” Hood said. “None of us thought it was going to pass in one year. We were pleasantly surprised.”

Hood and other autism advocates spoke of their 2016 legislative victory Monday during Autism Awareness Day at the Oklahoma State Capitol. They also discussed further efforts they said are needed to improve the lives of the thousands of Oklahoma children living on the autism spectrum.

“It’s life changing,” parent and advocate David Bloese said. “It affects thousands of families right here in our state.”

Bloese said some families may have to spend $40,000 to $50,000 a year on treatments and therapies if they can afford it.

“You’ve heard people cashing in 401k’s,” he said. “We hope we can keep making improvements on (the new law).”

‘There are still some gaps’

What Bloese means is that, despite the mandate taking effect Nov. 1 for state-based insurance plans in Oklahoma, families with autistic children have plenty of room to fall through the cracks.

For instance, SoonerCare (Oklahoma’s Medicaid program) does not offer coverage for things like applied behavior analysis (ABA), said Judith Ursitti, director of state government affairs for the national advocacy organization Autism Speaks.

ABA is a leading therapy to help with the development of autistic children.

“There are still some gaps,” Ursitti said of Oklahoma’s law. “It’s a federal mandate (for Medicaid programs), but Oklahoma is not in compliance.”

The Oklahoma Health Care Authority has studied the costs associated with covering ABA and other autism-related care. Sen. A.J. Griffin (R-Guthrie) said she hopes the OHCA is looking at ways to offer that coverage even though all state agency budgets are tight and uncertain.

“There’s ways for us to do that under the current services available in the behavioral health arena without adding costs,” Griffin said. “I wish we were looking at it, but with uncertainty and budget restraints, I understand the hesitancy to move forward now.”

Griffin was a co-author of the bill that created Oklahoma’s autism laws (Title 36, Sections 6060.20-22) and is Hood’s state senator.

“I was thrilled that we were successful,” Griffin said of the 2016 effort.

Some of that success, according to advocates, was thanks to Hood’s 9-year-old daughter, Chloe.

“She’s our power lobbyist,” Hood said of her middle child. “She would like to be governor, but she doesn’t want to dress funny.”

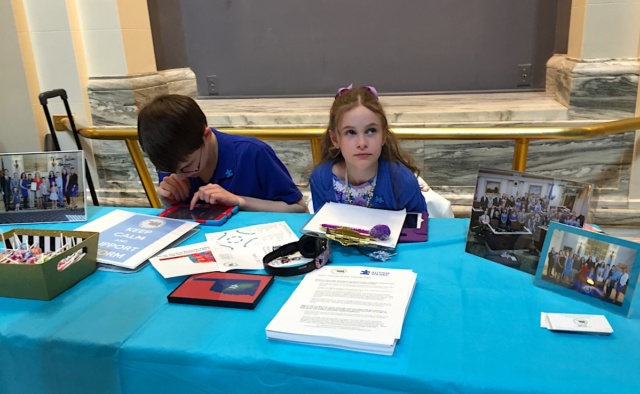

Sitting next to her 15-year-old brother Tristan Harrison, Chloe smiled and nodded in agreement when asked if that was correct. She said she enjoys coming to the Capitol and said she was “happy” Monday because “I haven’t been here in a long time.”

Harrison is also on the spectrum.

Asked what she would choose if she had the power to do anything in the whole world, Chloe Hood paused.

“Maybe to help people with disabilities,” she said, before offering an axiom that might seem beyond her years. “Like they say, knowledge is power.”

Autism affects about 1 in 68 U.S. children

Indeed, Chloe’s mother and other advocates said explaining the details of autism and its treatments were key to prevailing against an insurance-industry lobby that expressed fears of rising premium costs and “experimental” treatments.

“What I tried to explain to them was if you don’t provide these services to these kids at a young age, they will go on to need more services — which are usually more expensive,” said Dr. Tara Buck, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at OU-Tulsa. “Some people didn’t understand that we had data to support the evidence-based therapies like ABA.”

Hood joked that the fact Oklahoma became the 44th state to pass an autism mandate meant advocates had a lot of data at their disposal. For instance, about 1 in 68 U.S. children are on the spectrum.

“Everyone is affected by it either directly or indirectly,” Hood said. “(Legislators) need to see the faces and meet the families affected by autism.”

Ursitti, Bloese and others pointed to the importance of institutional knowledge that remained from 2008, 2009 and 2010 efforts to pass Nick’s Law, also an autism mandate.

“It was very close,” Ursitti recalled of Nick’s Law. “When we came back last session, there were still a lot of memories from that fight, from families and legislators and providers. They’d been fighting for a long time.”

With limitations in the 2016 law — such as an annual $25,000 cap allowance for ABA therapy — Ursitti and Hood said advocates will continue rallying for improvements.

“If you talk to providers around here about how many families (affected by autism) that they serve on Medicaid, they’ll tell you a lot,” Ursitti said. “So we just came down one Mt. Everest, and now we’re headed up another.”