(Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from the book John Joseph Mathews: Life of an Osage Writer. The book was published by the University of Oklahoma Press and is available here. The excerpt has been edited lightly for continuity and style.)

John Joseph Mathews’ debut work, Wah’Kon-Tah: The Osage and the White Man’s Road, rapidly made him a nationally recognized Indian author. Released in November 1932, it was based upon the “staid, meticulous diary of a Quaker Indian agent,” Maj. Laban J. Miles, the son of Benjamin Miles, an Iowa farmer, and Elizabeth Miles. The pair both taught Osage children and ran a small Osage boarding school in Pawhuska before returning to Iowa to teach Natives there.

Their son, Laban, met his destiny in 1878 when he was appointed agent to the Osages. Miles served the tribe in this capacity for many years and during various administrations, from 1878 to 1885 and 1889 to 1893. For 58 years, he was linked with the Osages, “a friend to the Indians and active on their behalf.” Although Miles left Pawhuska in 1893 when military officers replaced Quaker Indian agents, he maintained his interests in the town and spent time on the reservation, eventually returning to make his home there. Throughout his lengthy career of service, Miles kept a journal recording his experiences, an important record of Osage history.

After Mathews returned to Pawhuska, he met with the elderly Laban Miles, and they conversed at length as Jo took notes. Shortly before Miles died in April 1931, he contacted Mathews and said, “I haven’t got long and I want you to have my notes, my diary. It says plain old Quaker facts. You may have it, it’s yours.” Miles often felt frustrated that he was unable to express his feelings and understanding of the Osages in his writing, so he hoped his young friend might glean something from them.

‘Much confidence in an unpublished author’

It was fortunate that Joseph Brandt, the first director of the OU Press, apparently coaxed Mathews into writing Wah’Kon-Tah, since Mathews did not initially jump on Miles’s suggestion to use his papers, notes, and interviews as material for a book. “I didn’t think much of it until I started reading it,” Mathews admitted to Guy Logsdon. In April 1931, Mathews drove to Norman to see Brandt and his remarkable wife, Sallye Little Brandt. Mathews told the Brandts of his conversations with Miles, adding he would inherit the agent’s notes. This elicited an excited response. During the visit, Brandt handed Mathews a clipping of Miles’s obituary and said he wanted a book for the University of Oklahoma Press: “Go home and write it.”

In 1940, Time claimed Brandt “chased” Mathews across the continent in an airplane to spur him to complete Wah’Kon-Tah, and the magazine later said Brandt “wheedled” the book out of Mathews. “Jo-Without-Purpose,” as Mathews called himself retrospectively, benefited from such prompting. The critical and commercial success of the book, the latter largely the result of Brandt’s placing it with the Book of the Month Club, inaugurated Mathews’ literary career.

Miles’ valuable journals had already attracted literary interest. No less than the novelist and playwright Edna Ferber had tried unsuccessfully to acquire his journal while researching Osage County for her novel Cimarron (1929), which dramatized Oklahoma land runs and was adapted into two well-received films. In 1928, while Jo was in California, Ferber spent time in Pawhuska, her model for the fictional town of Osage. Jo’s relative, Phillip Fortune, claimed Ferber stayed at the Mathews family home and interviewed Jo’s sister, Lillian Mathews, about local history. While in Oklahoma, she took in sights “never seen on land or sea.” In Pawhuska, she found “Osage Indian houses built of brick, filled with plush and taffeta and plumbing,” and in the backyard, “tepees in which the owners preferred to sleep.”

In the early 1930s, Mathews and Southwestern author Walter Stanley Campbell, a professor at OU who used the pen name Stanley Vestal, reciprocated hearty respect for each other’s work. In January 1933, Mathews wrote his friend: “Our two books, Wah’Kon-Tah and Sitting Bull, seem in quite a different way to say the same thing, and certainly the relationship between the Sioux and the Osage is brought out. Our individual Indians have the same reactions and philosophy.” Of his forthcoming project, Mathews said in June 1931 both Brandt and OU President W. B. Bizzell were “rather keen on the prospect.” Campbell was apparently surprised and envious at the attention his protégée was receiving from OU Press. In 1967, Brandt wrote Mathews, “I suppose no publisher in history ever reposed so much confidence in an unpublished author as I did with you. W.S. never got over it.” After Campbell’s protracted struggles to achieve literary success, Mathews seemingly waltzed into a book contract.

‘I just wrote it because I had to write it’

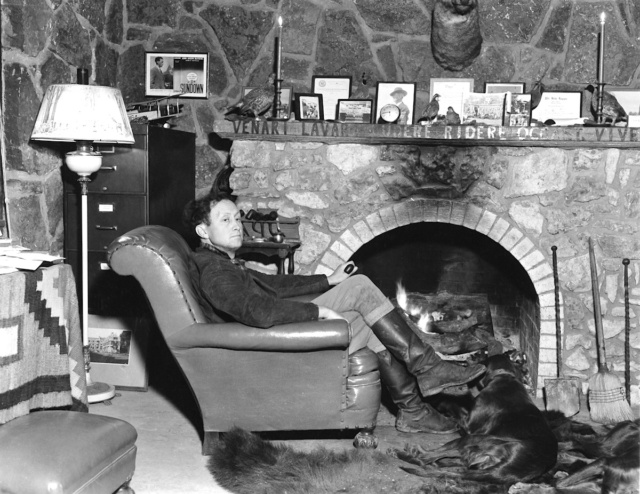

After returning to Pawhuska, Mathews found Laban Miles’ son, Oakley, and asked him if he had an old house somewhere. Oakley’s neighbor had an abandoned shack, 18 miles northeast of Pawhuska on Rock Creek, and Oakley helped Jo clean it out. The budding Osage author dived into an ascetic existence, his key possessions being a dog, a horse and a typewriter. He used a bucket to shower and ate canned goods and whatever he hunted or fished. He brought a record player and listened to recordings of Native music for inspiration. This was a trial run for his future life at The Blackjacks.

When news of Mathews’ project spread across Osage communities via the “moccasin telegraph,” elders sought him out to share stories about the early days of the reservation, augmenting his Osage perspective. Mathews commenced writing on July 4, 1931 — a symbolic date, since he asserted his independence and in Nietzschean fashion willed himself to become a writer. During this stretch, Mathews chose to isolate himself not only to write the book, but also to avoid contact with his estranged wife.

Composition flowed organically: “I wrote that book just like a wood thrush would sing. He’s not conscious of it, he just sings.” Mathews modestly stated, “I didn’t have any idea that people would read it or that people would be interested. I just wrote it because I had to write it. If I hadn’t finished it when I did, I might have gone deer hunting and forgotten about it.”