I have always wanted to be a patriot. I have always wanted to sing the national anthem as bold and black as Marvin Gaye in the 1983 NBA All Star Game. I have always wanted to celebrate Independence Day the way I celebrate Juneteenth, the day when the last population of slaves in the Confederacy were removed from bondage June 19, 1865.

I imagine you can’t be a patriot without celebrating the Fourth of July, and every year I am sadly reminded that my country’s celebration of independence — of the values for which we stand — was not meant for me. As much as I can tell, the best the country can offer is equity for a certain few to access the American dream and give window dressing to the improved place that African Americans inhabit. In reality, our quarter of society has been left as little more than a Potemkin Village in the City upon a Hill.

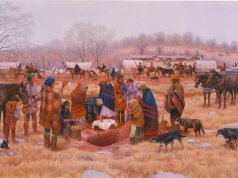

To know my history as a third-generation Oklahoman descendant from former slaves and Native American Freedmen is to know the hypocrisy of a country and a state for whom my identity and existence are inextricably linked. Despite my travels and adaptation to living amongst people from Kilimanjaro to the Cape of Good Hope, one thing has remained true: I am distinctly and inseparably Oklahoman. There is no going “back to Africa” or any place deemed more to my liking. America made me, and so to know the hypocrisy of which I speak is to know that, despite my existence being so singularly a product that only this grand experiment could produce, the men who founded the United States and a majority of their descendants who wield power and influence never meant for OUR country to be for me what it is for them.

When we exalt our first president for his bravery and virtue, I cannot un-see him as an unapologetic plantation master who owned others as property. When the current president likens his administration after Andrew Jackson, I cannot forget Jackson’s unapologetic, fervent support for chattel slavery and the Trail of Tears forced upon my ancestors of native descent.

We were told these circumstances were a product of their time. If that is so, then the only way we truly move past harmful history is to acknowledge and respond to it. Instead, I mostly see a country quick to excuse behavior of the past without acknowledging its impact on the present or the responsibility to invest in the future of those negatively impacted by it. That saddens me more than I am able to express.

Unrequited desire for a seat at the table

I have heard this refrain so many times reinforcing our evolving humanism. Perhaps Independence Day in 1852 was flawed for its hypocrisy during a time that an entire class of citizens was considered property of their neighbors, but today we celebrate the supposed embodiment of our founding ideals and principles more than ever.

RELATED

‘Orange-crested POTUS-elect’ likened to Andrew Jackson by William W. Savage Jr.

To that, I can only echo the sentiment expressed by Frederick Douglass 165 years ago, “What to the Slave Is your Fourth of July?” To me, it is still a traumatic and painful reminder of our often unrequited desire for a seat at the table.

Some will read this and see me as having no sense of gratitude or appreciation for the fortune that has come to me by being born in the United States of America. But my experience as a citizen primarily of African descent has felt like that of a bastard child longing for love and commitment to be reciprocated by its patriarch. Still, my country acts as the begrudging custodian who tells me I should be thankful he has afforded me a roof over my head, food on the table and clothes on my back, despite the dubious circumstances of my arrival. I am expected to be grateful for such security, even if it is not on par with his legitimate children.

After adopting the language and customs of our master and contributing mightily to his household, most of us would still desire if not expect to be accepted in some meaningful way as an equal member of the family. Instead, we are often met with incremental steps to our legitimacy. A proclamation here, a bill there; throw in an Amendment or two for good measure, but never explicitly acknowledge the heart of the matter, and never fully accept me as an equal.

To that, I say I am thankful but certainly not content with the station of those who share my heritage. Being content belies the reality of only the most incremental efforts being made toward acceptance that some of us cannot escape.

No involuntary servitude, unless …

Statistics tell us things have not changed as much as we may think. At the height of the civil rights movement, black unemployment was 10.9 percent. Today, it is 12.6 percent. In the 1960s, 76 percent of black children went to majority-black schools, and today it is 74 percent. Blacks were being incarcerated at five times the rate of whites during a time of Jim Crow laws and state-endorsed racism. Today, it is 6.5 times that of whites, and America has the highest incarcerations rates in the world.

So when I quote the words of Frederick Douglass, it is not so much metaphor as alternative perspective. The 13th Amendment, one of the earliest window dressings responding to the circumstance of black citizens, “prohibits involuntary servitude, except in the punishment for a crime.” Historically, America’s justice system has been inconsistent when it comes to its black citizens. For me to believe we have overcome that history while still confronting a system that is not responsive to inequitable incarceration and the growing prison industrial complex seems foolish.

I have heard that if we followed the law, we would not have to worry, but current events remind us how tricky that can be. I am repeatedly haunted by my adolescent experience in the 1990s, growing up with labels like super predator and menace to society. Every time I hear about the unnecessary deaths of black men at the hands of those who are sworn to protect us, I think of those labels. We were told that society had learned and moved beyond the police brutality exposed in the 90s by episodes like the Rodney King beating. We thought that meant we were no longer at risk of death based on law-abiding interactions with police. But then come the tragic deaths of Philando Castile, Eric Garner and others.

In each case, the outcome reaffirms that we are still a group that can disproportionately befall the fates and the treatment of Dick Rowland or Emmett Till. Even if whistling at a white woman walking down the street or selling cigarettes without tax stamps are crimes, they should not be worth our lives. It should not be expected that, in order to be accepted, we have to play by a different set of rules. In order to be protected, we should not have to relinquish our right to equal treatment under the law. We should not have to beg forgiveness for the original sin of our skin color. We should expect explicit biases — such as the very first piece of legislation passed after Oklahoma statehood — to be stamped out of every law in the land.

Indeed, we must acknowledge that those Oklahomans in power in 1907 passed laws that treated my grandfather (born the same year) as a second-class citizen whose life mattered less than his white neighbors. Those laws and the way they shaped our society created implicit bias negatively affecting his offspring.

These are our problems to fix

To be clear, I see no part of my history in any way an excuse to wallow in some static sense of victimization. I believe in God and think that the creator will often burden those with the broadest shoulders. These are our problems to fix, and it is our responsibility to fight for the changes that we wish to see in our circumstance by all the means available.

What I pray for is an acknowledgement of both how far our country has come and how far it still has to go. I desire recognition that my history is just as valid as the celebrated history of our founding fathers, and I seek an understanding of why I cannot be an accomplice to the Fourth of July’s celebration of freedom and liberty without solemn recognition of the debts unpaid and the deeds undone.

Today, I hope to share that burden with you. Let us at least agree to acknowledge our shared experience and work just as hard to fully and equitably invest in all citizens as we do to celebrate what has been accomplished.