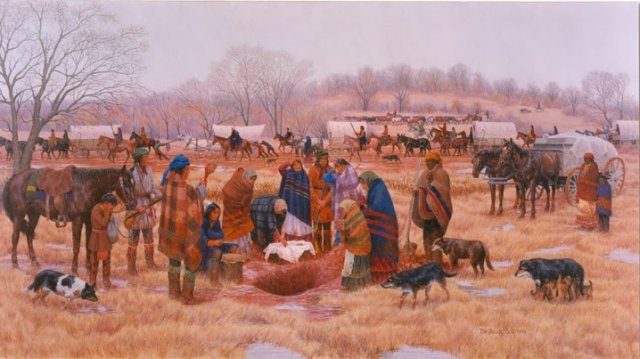

When Andy Fraizer was 5 years old, he made the treacherous passage with his father from his Chickasaw homeland to Indian Territory.

According to stories passed down to Fraizer’s great-great granddaughter, LaDonna Brown, he never forgot the silence that accompanied the travelers on the cold November day when they began their journey.

This story was reported by Gaylord News, a Washington reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Oklahoma. This series entitled “Exiled to Indian Country” details the stories of how each of Oklahoma’s 39 tribes ended up in the state.

“He said it was strange,” said Brown, a Chickasaw historian. “Of all those many people, nobody said a word. Nobody said anything.”

That moment in Fraizer’s memory may have served as a solemn prologue to the Chickasaw Nation’s tale of resiliency maintained in the face of hardship.

After President Andrew Jackson convinced Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Chickasaw leaders made multiple trips to Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma, to find suitable land.

The tribal leaders found none to their liking, and the tribe resisted removal until 1837, when invading settlers and threats of war from Jackson finally forced them out.

While other tribes had left behind their livestock and possessions to make the journey more quickly by boat, the Chickasaw’s leaders knew that packing everything into wagons and making the three-month trek across land would better serve the tribe in the long run.

“Our leaders had heard about all of these things that had happened to other tribes, and they wanted to make sure that these bad things weren’t going to happen [to the Chickasaw],” Brown said.

Although the federal government promised land fully-stocked with tools and gardens, they had heard from other tribes that the promise had not been kept.

Additional stories of over-worked steamboat engines exploding had made the water route impossible, but travel on land presented its own challenges.

“People died from food poisoning, they contracted dysentery from very, very warm days and cold nights and they were also dying of starvation,” Brown said. “They didn’t know what was going to happen to them, but they just had to keep going forward.”

Chickasaw Nation citizen Wendell Pettigrew said that when his great-grandmother and grandmother passed through certain towns, they were forced to hide the devastation of the trail and present a false show of happiness.

“When you’d pass through a town, they’d say, ‘You’ve got to be happy, or you don’t get fed,’” Pettigrew said. “You would have to be happy, dress up and go through the town singing like you’re happy.”

Even for the Chickasaw who survived starvation and disease, their new home was far from welcoming.

Pettigrew said his grandmother was killed as a result of bounties placed on Native American scalps by the local government.

“She was killed by Indians, because they would do the same thing: get the scalp and sell it to the white people, and they would split the money for it,” Pettigrew said. “They don’t tell you that in story books or history books.”

A lack of autonomy

The Chickasaw leaders had not selected government-sanctioned land in the years prior, so they purchased an interest in land and resources from the Choctaw through the Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw in 1837.

As a result, the Chickasaw had to abide by the laws of the Choctaw Nation and could not settle Chickasaw issues without Choctaw influence until the two tribes separated in 1854.

“Our leaders were like, ‘This is not working. We need to get out of here, because we need to take care of our own business,’” Brown said.

Although the Chickasaw had lost much of their legislative independence, Chickasaw Nation dancer Jesse Lindsey said they held tight to their cultural identity.

“Once [the Chickasaw] got to Oklahoma, [the government] said we could no longer do our dances (and) no longer speak our language,” Lindsey said. “So, what we’d do was go deep into the woods and start our dances at midnight.”

Decades of secretly preserving traditional dances and language became a vital part of the Chickasaw Nation reaffirming sovereignty in the eyes of the U.S. government about a century after its removal.

“That’s when the government said that, ‘If you didn’t have a song and didn’t have your language, you couldn’t be recognized by the federal government,’” Lindsey said. “But we kept our song (and) kept our language, so we were one of the (…) tribes recognized.”

Chickasaw Nation citizen Kendra Farve said the Muscogee (Creek) and Choctaw tribes also helped to preserve Chickasaw songs and culture.

“It’s just that brotherhood, that camaraderie,” Farve said. “We all lost something in the removal, and that understanding that we all lost something really helped us get our roots back.”

RELATED

The Cherokee story of preserving an endangered culture by Aimee Lewis

But the connection between the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations did not arise as a result of the removal. Rather, it has run deep for about 15,000 years.

According to the Chickasaw Migration Story, the Chickasaw and Choctaw were one tribe until the tribe’s leaders, brothers Chiksa’ and Chahta, decided to take separate paths.

Although Chickasaw and Choctaw roots have been tied together repeatedly throughout history, Brown said this has only strengthened the resolve of the Chickasaw to preserve their own identity.

“People, they may lose everything, they may lose family members, they may lose everything that they ever owned,” Brown said. “But the one thing that they can point to is that they’re Chickasaw.”

Brown said no characteristic separates the Chickasaw more distinctly than their perseverance.

“It’s something that’s natural, that they’re born with,” Brown said. “They have to keep going.“